I started thinking about how products emerge from specific places after a friend sent me a social media profile called “NYC Hood Hoppers.” I swear I walked around the city differently for a few hours after seeing it, gloating that thousands of people were entertained by representations of a very nostalgic community, built around 2000-10, that I was a part of. I’ll never forget a meme that read, “if you weren’t around when he skated with his twin girlfriend then you definitely not from here.” (At one time, skateboarder Nate Rojas and his girlfriend had similar-length hair and were always together with their skateboards and skinny jeans.) Though their style proved to be ahead of its time, it wasn’t just the portraits of this group of skaters that called attention to the page. The “you wasn’t there” tone joined other memes that posed a fundamentally fair question: if you are not from New York, why should you start a skate brand based on skateboarding culture from New York? I was cracking up. People were getting “flamed,” including brand founders and high-profile professionals. It wasn’t quite nativist—most New Yorkers aren’t anti-immigration—nor was it a complete shade room, but the topic did grab the community’s attention in a spirit of anti-gentrification.

Around 2008, Mike Wright’s “I Skate New York” T-Shirt replaced the heart icon of the classic “I <3 NY” T with a skateboard, selling hundreds of units. Skateboarders love NY, the capital of American commerce that also harbors a large and accepting community of people who skate street terrain. It makes sense that these transplants saw the value of the space they entered. All of this encouraged me to question how product emerges, and in what relationship to where? Canal—another skate brand established in 2013—has fittingly produced logo interpretations of tourist Ts sold on Canal Street. NY skate brands may not sell the image of an NYC skyline; however, there is a metaphorical equivalent and they are people. The product’s value is asserted through the corporal real estate of the person wearing it. But where does the commodity come from: the body or the space? Here, I will use Supreme—now one of the most mythical brands of all time—as a case study for how the social and site-specific nature of fashion products has come to define their value.

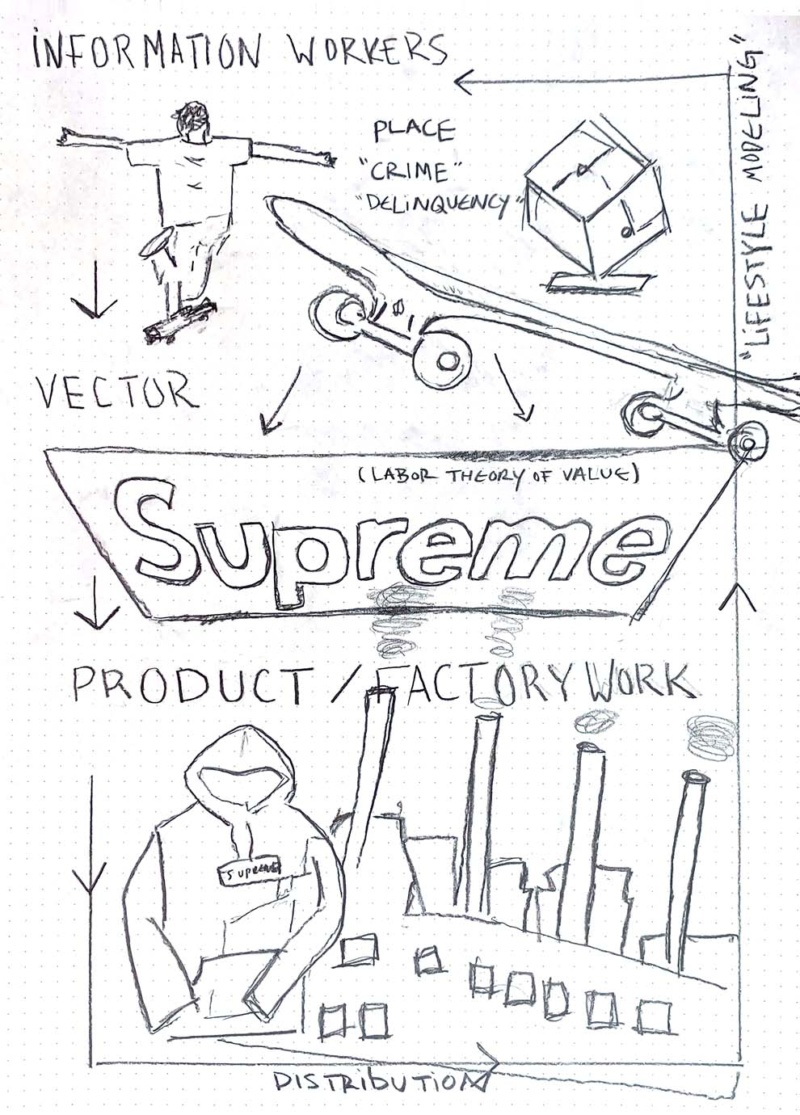

Nobody doubted that a small group of skateboarders and street captains, gathering in Lower Manhattan over three “skate generations,” conspired in the formation of a new, information-based economy. Perhaps it is also not hard to believe that the way this information was translated into commodities—into decks and hoodies and T-shirts—actively contributed to defining value and discourse in the period some call “post-capitalist.” Capitalism has moved beyond the structure of two dominant classes (capitalists and workers) and now includes the production of malleable information. Brands, coined “vectors” by scholar McKenzie Wark, work with information producers to develop “new information,” usually by reinventing references or sourcing ideas from groups of people. These information producers are skaters, designers, artists and curators, people who use map apps and social media, programmers and beyond. At the very top are the owners of the intellectual property related to the vector. Supreme joins “tech” brands in the vector class while outsourcing manufacturing to factories that make everything from apparel to plastic trinkets.

While information is abundant and amorphous by definition, situating it in relationship to physical places uncovers some of its logic. Supreme was built on an exclusive, “you can’t sit with us”-type of cultural knowledge about Lower Manhattan, correspondingly an epicenter of global capitalism. Skate spots like Brooklyn Banks are only a ten-minute ride from the Wall Street Bull, where people hedge the direction of the marketplace at the Stock Exchange. Founded in 1994, the same year Rudy Giuliani was elected Mayor of New York with the goal to be “tough on crime,” Supreme’s first spatial and temporal relationship is to crime. Delinquency is a crucial component of the information the brand has been developing over the past thirty years. Founder James Jebbia, once a factory worker himself, migrated to NY from the UK at age nineteen, where he helped open Union NY and then Supreme, a skate shop on Lafayette Street, as part of a wave of streetwear businesses in the area that included Keith Haring’s Pop Shop.

Though its clothes are of objectively good quality, that is not why Supreme became so valuable. To build authority on the style and cultural practices of Downtown, in situated relationship to the formal economic production that Wall Street contributes to the entire world, is hugely powerful. The Empire State benefits from intimate knowledge of crime and degeneracy at the margins by working this information to aesthetically mediate the spectacle of prosperity supposedly pouring out from the center. Homeless and unemployed people regularly appear in Supreme’s videos, joining skaters in fueling sales. Every piece of the equation, even unproductive and illegal activity, from kicking wood to smoking dope to graffiti, eventually becomes productive in some capacity; this is the power of empire, of its heart Downtown and of the arteries of information flowing from it. It is no surprise that the information produced in the literal cracks, ledges, security gates and handrails of the market’s center has influenced its direction.

Designing product that is relevant to a small group, located in the right place, seems to be the “trick” to harnessing information with global market relevancy. Beginning in the spring of 2017, BRUJAS, with ethnic (Latinx), gender (female) and place (The Bronx) niche qualifiers in skateboarding generated millions in mood board inspiration for retailers. The group, which I helped found, was cited by Vogue magazine in a twenty-year retrospective of Supreme as co-opting the brand with an “impressively genderless approach to dressing and living.” No matter how big the company gets, the logic of “small groups” remains integral to its marketing narrative. For its biannual drops, a curated list of NYC brand reps receive a catalogue from which they select three items in each apparel category. Getting “seeded” Supreme is a status symbol for Downtown cool guys, but the product is not necessarily “free,” in the sense that this group consents to representing the exclusive base of a billion-dollar company. In the effort to expand, Supreme built out the vector for these groups—street teams, muses, models, shop employees, vandals, artists and skateboarders—at different stores in other major cities: Los Angeles, San Francisco, Paris, Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, Fukuoka and London. The store managers and teams from each city get to know each other through travel and skating, building a transcontinental bond over their shared lifestyles which is mediated through the brand. This is somewhat consistent with the logic of Whiteness: create an exclusive “group” based on an elite social and financial positioning, then build their power by absorption.

Fast forward almost thirty years, and what was once an “insiders” club of self-identified “outsiders” is valued at a billion dollars by The Carlyle Group, a multinational private equity firm. The Carlyle Group purchased a fifty percent stake in Supreme in 2017, resulting in a 500 million/500 million split between Jebbia and the portfolio, which holds 193 institutional investors including Morgan Stanley, Bank of America and Chase. The Wall Street Bull and the Brooklyn Banks’ short-distance relationship starts to unveil with facts.

In Luc Sante’s cult classic text, Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York (1991), he writes in the preface:

“the ghosts of Manhattan are not the spirits of the propertied classes; these are entombed in their names, their works, their constructions. New York’s ghosts are the unresting souls of the poor, the marginal, the dispossessed, the depraved, the defective, the recalcitrant. They are the guardian spirits of the urban wilderness in which they lived and died. Unrecognized by the history that is common knowledge, they push invisibly behind it to erect their memorials in the collective unconscious.”

Streetwear—if anything at all anymore—is an expression of the collective unconscious of delinquents. You cannot watch designers attack the same ideas, in uncoordinated fashion, season after season, without realizing that there is a visual and political discourse being accessed and shaped by those who are “tapped in.” Perhaps designers and art directors are tapping in with guardian spirits, or maybe they are simply outside, adapting to the newest inventions of property by the owning class. Bad creative directors get their inspiration from the internet, but the outdoor sensibility of style never quite translates into online images.

Supreme’s objects and apparel are designed for Sante’s “urban wilderness”—Swiss Army knives, camouflage, water bottles, wheels— and there is a strong underlying “survival of the fittest” messaging that coordinates itself well with market logic. Yet fitness, like style, requires context. NY is one of the most expensive cities in America. In a skater-wide survey conducted by the Harold Hunter Foundation, sixty-five percent reported having an annual household income of less than $40,000. The only skateboarding nonprofit organization in NYC that authentically serves low-income populations has received only very small donations from Supreme. Public good and community are not values the company expresses often. Growing up, I remember the ledge obstacle they dropped on 12th Street and Avenue A being about waist-high—too high for the majority of the park to skate.

The repeated nostalgia for the degeneracy of the brand’s constituency further complicates this skate-Darwinism. Aaron “A-ron” Bondaroff (now excommunicated from the scene because of repeated allegations of sexual assault), who modeled their “lifestyle” professionally, has called these individuals “train-hopping, taxicab-jumping, runaway kids.” As previously mentioned, Supreme’s founding in 1994 coincided with the city’s “war on crime.” Between 1994 and 1997, misdemeanor arrests shot up by seventy- three percent and prison populations soared in the wake of “broken windows” policing. The survival of poor Black and Latino teenagers, young adults and their families was under direct threat.

For Supreme to extract from the same populations the city is actively disciplining, without creating equity or advancing justice on behalf of the brand, all while upholding exclusivity and social fitness as tenets, unfortunately reveals much of Supreme’s legacy as yet another commercial manifestation of carceral logic. Its position further amplifies the disillusionment that the state relies so heavily on: only the best don’t get caught. This is not to say that Supreme has not also built positive foundations for skateboarding and for design, but the implications of their extraction and its transference into carceral capitalism only grew more transparently dangerous as the brand expanded.

The worldwide or “world-famous” presence of Supreme’s retail outlets also became more internationally implicated with The Carlyle Group’s investment. When commodified, local obsession can ultimately become materially nationalist. Skateboarders—mostly youth of color in Lower Manhattan—have convinced a global consumer base to spend millions annually at an American company. Even if the culture consumed is anti- establishment and features marginalized and policed bodies, the money moves with the reality of American hegemony.

Some of the companies The Carlyle Group is or has invested in occupy the categories of “government” and “defense”; these include the Dynamic Precision Group, which produces military aircraft engines; Novetta Solutions, a software company that offers “solutions to detect threat and fraud, and protect high value networks for the government”; and United Defense Industries, a “leader in the design, development and production of combat vehicles, artillery, naval guns, missile launchers and precision munitions.” Some people reading this analysis may misunderstand my critiques by assuming I’m implying that the trajectory was somehow masterminded by Jebbia, or even in his control. Every teenager needs something to punch and perhaps, at least in theory, Supreme is helping to grow the anti-position away from minority scapegoats and towards the government. Multiculturalism, a truly liberal self-purpose, is written all over the brand story. However, in practice, collecting and selling information on delinquency is a dangerous game. Tracing how this information becomes both materially (as part of cash pools for weapons developers) and ideologically disciplinary (people in fashion resist speaking out against the Supreme mafia for fear of being black-balled or fired) can teach us about the emergence of new systems of policing. Supreme has collaborated with the police on a local, national and even global level, all while selling hoodies, T-shirts and hats printed with images of burning cop cars (these items were part of the FW19 collection).

On any given Thursday, when Supreme “drops” new clothes, the NYPD regulates the lines. The same police that will ticket you, confiscate your skateboard and arrest you for skating on private property cooperate in the distribution of products. I’ve witnessed first-hand officers leading groups of kids in single-file lines down the street to the entrance of Supreme’s Brooklyn store. In the process of selling back “outlaw” culture, Supreme actively puts their consumer in contact with the police; for many with open cases, warrants or parole, this means danger. Therefore, the brand’s very muses risk the most as consumers.

Last summer, an article about an altercation at Black Rock, a local skate spot in San Francisco, between the GX1000 skate crew and an irate security officer was published in The New York Times. The encounter resulted in a life-altering brain injury for the security guard and the jailing of pro-skater Jesse Vieira. The authors reference skateboarder Tyshawn Jones’s appearance in Supreme’s 2019 video Blessed, arguing that it glamorizes conflicts between skateboarders and security. The skate team, who physically model Supreme’s clothing, also model the desired consumer’s position in relation to power. The spectacle of conflict between security/police and consumers/skateboarders is welcome, even in stores, as it ultimately contributes to the spectacle that makes their goods sell.

Select Supreme products themselves embody this conflict. The Supreme-branded crowbar, an often-weaponized object used to pry open doors and windows, released in the FW15 collection (which also included a windbreaker reading “Justice For All”), most concisely represents the driving narrative of criminality. The infamous Supreme brick, released the following fall, has been described as a play on the slang for a kilogram, or a pound of cocaine. Though Supreme sells some kind of drug, it’s not the illegal kind. Yet this clever sale was constructed with information gathered from people who actually do break the law to survive.

The plot continues to thicken because crime and geography, central to Supreme’s production style, are both heavily racialized within our society. Race is not a weapon in this analysis, but rather an essential context that brings the spatial logic of economic extraction into solution building. A FW19 Dead Prez collaboration, the SS18 Martin Luther King capsule, the Public Enemy Fear of a Black Planet pieces from the same season, the Harold Hunter Comme des Garçons collaboration of SS14 and, finally, the 2010 Haile Selassie T-shirt, all comprise a critical thread in Supreme’s messaging. My personal favorite was a SS08 T-shirt with a red, black and green American flag, mapped into an anarchist symbol and printed on pink cotton, that I received in a product toss at the King of Spring skate competition. Black nationalism, which rose to popularity and influence in the US during the Black Power movement of the 1960s (but originated much earlier in the 19th century) advocates for self-determination for Black people, often by conceptualizing a separate and liberated Black Nation. The red, black and green colorway comes from the Pan-African flag designed by Marcus Garvey.

While Supreme contributes to the US materially through the international distribution of branded goods, Black nationalism recognizes how economic, cultural and government apparatuses alike build and protect power and value together. But without the existence of a Black nation, what is achieved when Supreme sells images of a Black radical politics, or even of Black people? Who benefits from the circulation of these images? And, for skateboarders who are constantly having their photos taken Downtown, this question begets another: what is in skateboarders’ best interest? Might demanding territorial autonomy be a necessary protectionist trade policy, this time for skateboarders? What would it look like if we had our own piece of the city?

Ultimately, I believe Supreme does want a piece. Adam Zhu, an up-and-coming creative influencer at Supreme, gathered 33,000 signatures to save Tompkins Square Park’s “Training Facility,” a heritage site for Downtown skaters that was slotted to be redeveloped with AstroTurf. The victorious defense of this territory is a prime example of action that advocates for respect, not extraction, for the community and the inspiration all skateboarders, not just the best ones, resourcefully provide the world. A week later, “Save Tompkins” T-shirts were for sale at Supreme’s Brooklyn store, where Zhu works. Young people in and around the brand, and in the city at large, are demonstrating awareness of their own value through design and action, hopefully encouraging Supreme to help incubate the conversation around what can and should come next. Only one thing is for sure: the police and their weapons will have no part in the build. Regardless of where we come from, all skateboarders should be able to agree on that.