I encountered Public Housing Skate Team for the first time almost three years ago, on a sweltering Saturday afternoon in September on the fifth floor of a nondescript commercial building on Canal Street where they, and I, were both vendors at a market for small brands and artists organized by Gogy Esparza’s Magic Gallery. In one corner, Ron Baker and Vladdimir Gomez were selling merchandise behind a police barricade that appeared to have been sawed in half. Their stock included hoodies—one embroidered with barbed wire, another with straight razors—a T-shirt with a drawing of an NYPD helicopter beaming a search light and a skate deck printed with a notorious news image from the 2003 police raid of an apartment on Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard that was home to a Siberian-Bengal hybrid named Ming. (Though a neighbor had complained to housing about the tiger in 5E, her message was never answered.) Projected on one of the gallery walls was a documentary Vlad made about his uncle, which overlaid live footage with private voice memos that he discovered when gifted his uncle’s laptop.

Poetic, often allegorical storytelling characterizes both Ron and Vlad’s individual practices as artists and what they have created together as the cofounders of Public Housing Skate Team (PHST). Vlad has produced other experimental films, such as Rosewood (2019), a hybrid horror documentary about a variety of sinister happenings at Bronx Park East that was somewhat accidentally featured in a News12 segment. A few weeks prior to this interview, I saw a selection of masked sculptures Ron constructed from clay, cowrie shells, rosary beads and palm leaves at a group show curated by Kiara Ventura at Longwood Art Gallery. On a nearby wall, a time-lapse film recorded the growth of a money tree he placed in the lobby of his project building, along with carpets in the shape of hundred-dollar bills and a selection of inspirational books. He tells me that he asked the housing manager about the possibility of installing these carpets wall to wall, but was told the result would not be sufficiently “uniform.” I am reminded of Thomas Hirschhorn’s Gramsci Monument, a collaboration between NYCHA (New York City Housing Authority) and Dia Art Foundation that took the form of an 8,000-square-foot participatory sculpture at Forest Houses in Morrisania in 2013. That this transformation, devised by a German artist and commissioned by a major museum, was permitted is perhaps not surprising. It is, however, representative of the barriers NYCHA residents face in claiming autonomy over and within their environment, and of PHST’s intentions, which I was able to discuss with them for the occasion of this article.

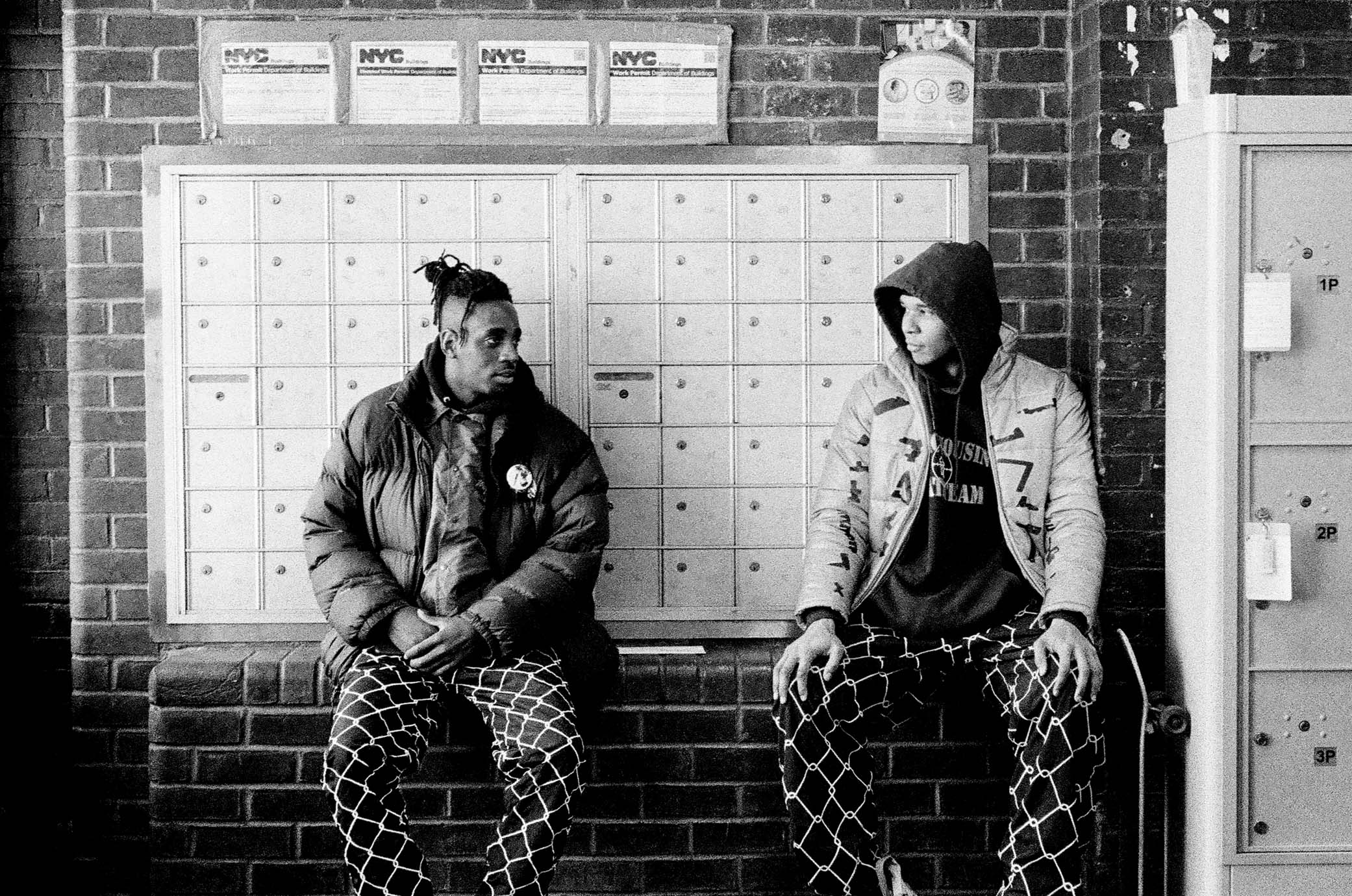

We meet outside the Gun Hill Road stop on the 2 train and walk a few blocks to Gun Hill Houses, where PHST was born five years earlier. Ron and Vlad are joined by Shawn Torres and Neil Figueroa, two team members who hail from the South Bronx, as well as videographer Muhammad Floyd and photographer Koki Sato, both frequent collaborators. Ron and Vlad grew up neighbors in the complex and got to know each other playing basketball. It was common for projects to have their own basketball teams, but they wondered if there could be something different, something that would be their own.

While PHST is perhaps best known for its clothing, it is not technically a streetwear brand. As its name makes clear, it is a skate team and, like most skate teams, its business model aspires toward a feedback loop in which the output of skateboarding content (videos) encourages clothing sales that generate revenue to support the team. Skate teams that sell clothing and hard goods are hardly new—Supreme being the best-known example—but, before PHST, there had never been a skate team representing a housing project. Ron and Vlad set out to create something different both for their community and from other skate teams that had come before. What would Public Housing Skate Team look like, and what would it mean?

Everything PHST makes has a distinct conceptual approach, deeper than a visual affect and closer to a narrative treatment. THUG, their first film from 2016, is part skate video, part action flick, part satire, and merges references as divergent as cult Japanese mob movie A Colt is My Passport (1967) and ’90s street rap. PHST’s citations are often esoteric. Vlad tells me that he used to visit New York Public Library locations across all five boroughs and take out the maximum number of DVDs permitted, watching anything he could get his hands on. Ron shot the grainy, almost-ten-minute short, in which Vlad (dressed in a white bathrobe and a du-rag) turns a gun into a skateboard, making literal what skating is to them: a weapon and a means of protection. Its title is an acronym for Tony Hawk’s Underground.

Subplots punctuated with dark, ironic humor can also be expected of PHST’s films; in Eviction Notice (2016), skateboarder Shawn Powers learns he can no longer live at his apartment and proceeds to trade his board for a tricycle. Layaway, of the same year, intersperses skate footage with acted fragments; following a pleading phone call with an ex-girl, full of promises that he’s changed his ways, Powers literally digs his own grave. His board doubles as a headstone. More traditional videos such as Closed Circuit (2017) set clips to classic radio freestyles in a style reminiscent of early crossover compilations such as the famed Zoo York mixtape of 1997 and the AND1 mixtape series released from 1998-2008. But despite their sharply intentional detail, these films are never slick or overproduced. They feel, instead, at once much older than they really are and totally out of time, like a memory or a dream.

Ron and Vlad underscore that the creative culture of ’90s New York is crucial to their vision—an obsession that seems to define our times and leaves me wondering what about this era is so attractive both to brands and to consumers today. To PHST, it’s an attitude defined by Hip-Hop: an ingenuously inventive approach to limitation paired with a realness pulled directly from everyday life. In the wake of globalization and gentrification, it is hardly a surprise that contemporary retromania mourns this ever-elusive “authenticity.”

But maybe the particular appeal of that time is also part of a larger story about the direction of fashion—and of culture at large—over the last three decades. In 2002, famed Jordan brand architect Erin O. Patton was invited to speak at an annual marketing conference themed around “targeting” urban consumers. In his speech, Patton set out to explain what exactly “urban” meant, especially in the context of selling things. This term, he argued, was no longer a demographic category for people living in densely populated areas; instead, “urban” had become a psychographic: “a mindset shaped by the cultural phenomenon born in the 1970s called Hip-Hop” and now applicable to all kinds of people with no actual experience of city life.

PHST both embodies and resists Patton’s theory. As what they make is so directly informed by the literal conditions of their lives, one of Ron and Vlad’s biggest concerns is preserving a meaningful connection between their output and its context—a priority as rare as it is complex. “The guy on the corner is our biggest inspiration and he doesn’t even know it,” Ron says. “He’s wearing what he’s wearing because he needs to be outside for twenty hours selling drugs, but his style will end up on someone’s mood board in Paris.” He names an enduring phenomenon that has only become increasingly obvious in the past thirty years: the transformation of formerly hyperlocal cultures and underground creative movements into a global mainstream. When I ask if PHST has any direct references from skateboarding, Vlad mentions a few teams—Kareem Campbell’s City Stars and Baker—but Ron maintains that his only inspiration is “Hip-Hop and the environment,” citing iconic tribes such as Wu-Tang Clan and Ruff Ryders. While it is undeniable that Hip-Hop, skating and streetwear—each once synonymous with specific localities and communities—have permeated every corner of the world (due in part to the mass media but also to the branding initiatives that consultants like Patton advised and enabled), each’s journey to a larger audience has relied on extraction and erasure. But, as PHST insists, meaning cannot be made without context or without history.

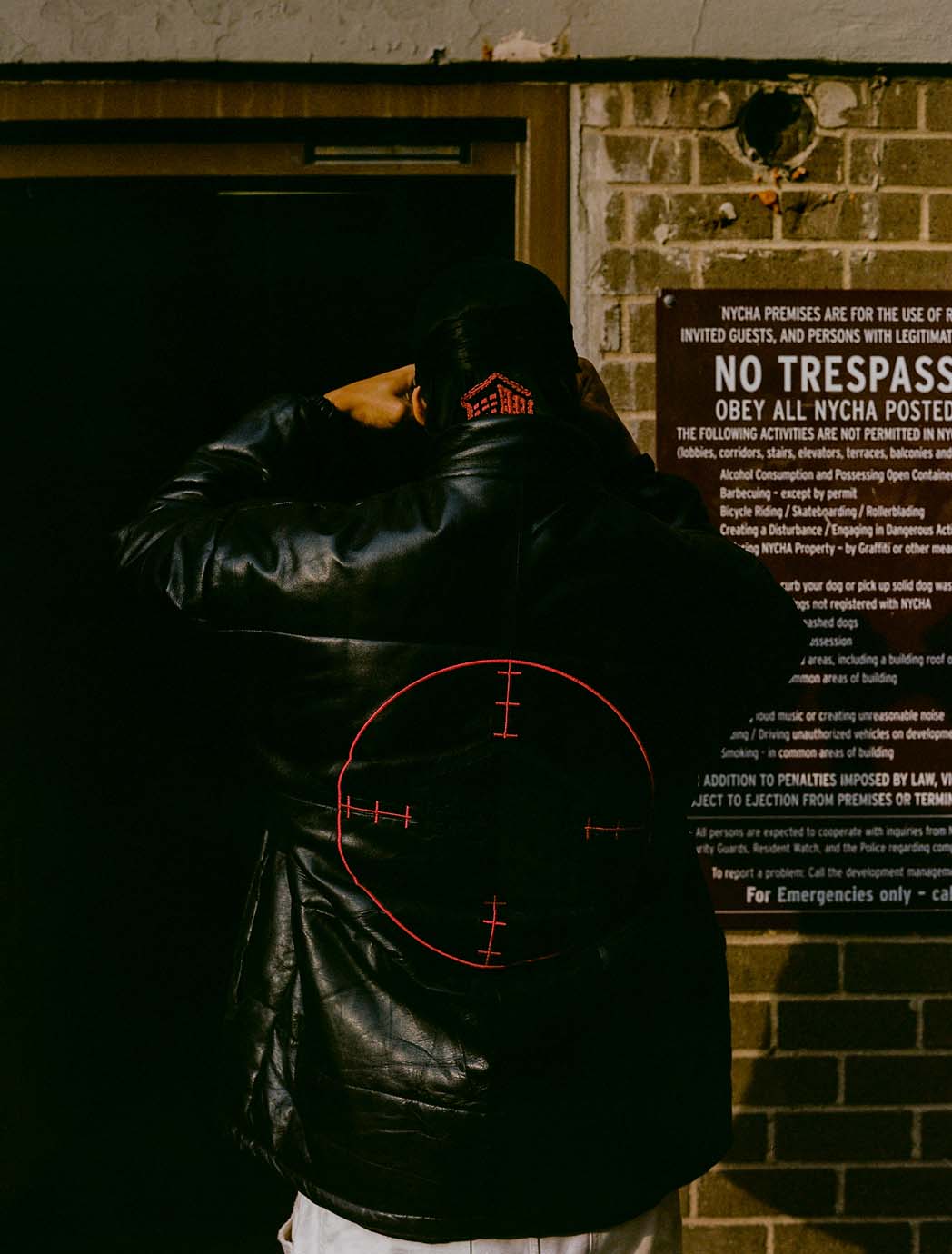

The level of thoughtfulness and execution in PHST’s merchandise stands far apart from the redundant, logo-heavy basics churned out by many young brands. Releases that caught my eye include sweatshirts printed with an allover pattern of exposed brick punctuated by embroidered bullet holes, jeans embroidered with a chain link that, if you look closely, breaks in several places, and a skate deck that juxtaposes Fine Fare coupons for bologna and Hawaiian Punch with security camera stills of individuals caught in the act of shoplifting (a store location in the Bronx granted them permission to use these images). Their logo, which appears on select items, combines the NYCHA icon with the crosshairs of a target. On the day we meet, Ron’s apartment is being treated for lead, prompting conversation around a forthcoming design in which the letters mimic the way paint peels.

As I write this, and the past few times I’ve checked, everything on the PHST website is sold out, indicative of the fact that their goods are not particularly easy to come by. Of course, scarcity and streetwear go hand in hand—manufactured drops, spectacular lines, scrambles at resale—but PHST is conscious about the way it presents to the world for reasons more critical than hype; its preoccupations—integrity, impact, legacy—have more in common with art than with fashion. These considerations map across all their modes of engagement, from partnerships (they have turned down many with big and small labels alike) to stockists (they have none in New York City). “You don’t see us collabing with a lot of brands,” Ron admits. “From a business perspective, it might not be the best. Has me thinking sometimes, ‘is this a business or a hobby?’” Like many independent creative ventures, they face a seemingly impossible but not unusual “ethical” dilemma: is maintaining integrity contingent on sacrificing monetizable success? The choice is between cashing out when the opportunity arises or watching while bigger businesses brazenly misappropriate your ideas. “If you accept that check, it’s over. That will be your last check,” Ron says knowingly, for it is resistance itself that corporate enterprise lusts after in its search for the few remaining accolades—realness, relevance, respect—that cannot be bought or sold.

Skating, by nature an outsider lifestyle, has come to epitomize that very rebelliousness. Context contingent by design, street skating relies on finding unique spots in the built environment. This is one thing that sets the Bronx apart, they tell me, as skating is still less common than in other parts of the city, especially Downtown. Apart from the Bronx County Courthouse, most spots haven’t been publicized in popular skate videos, on social media or in advertisements. “People are scared to come here,” Vlad says, laughing. In general, the presence of skating in advertising as a symbol for counterculture is often contrived to the point of absurdity. “Brands trying to use skate culture for clout is like showing up to a party that you weren’t invited to,” Vlad remarks, describing a major luxury brand’s window that displayed a skateboard with the trucks on backwards. An upside is that some skaters do receive acknowledgment and professional opportunities that weren’t possible before; still, commercially motivated appropriative practices rarely put on the right sources or people.

But Ron and Vlad are far less concerned with cashing in on trends than they are with simply staying around and making a mark. Visions for the future revolve around becoming a community fixture, a team that young skaters like them could aspire to be on. “We want to motivate another generation of Bronx kids living in the shadows,” Ron explains. “We want to let them know they can make something from nothing, just like Hip-Hop.” “To many, the Bronx represents people of color, poverty and the projects,” Vlad continues. “But there’s a bigger picture.” He stretches out his arms to show me that the seemingly abstract arrangement of rectangles on his 3M bomber jacket is a bird’s-eye-view of all the project buildings in NYC. Though this one is an exclusive, they plan to drop a jacket for each borough. The resolve to see far while staying close may be PHST’s most profound agenda and its greatest challenge; if success is contingent on finding an audience outside of where you’re from, how do you steer recognition and resources back home?

Ron and Vlad are in the middle of planning a pop-up. This will not occur in a day-rate rental space on Bowery or in the retail location of a partnering brand; it will happen in the same building I visited to conduct this interview, prioritizing the convenience of their local audience while physically prohibiting the divorce of their merchandise from the conditions from which it came. Clothes will hang from the windows in their staircase. Skate footage will play on a projector. Ideally there will be a DJ. After all, Hip-Hop was born of these same makeshift shared spaces. Almost fifty years ago, DJ Kool Herc threw his first party in a building rec room not far away. “The Bronx inspired the world,” Vlad says. “We have to represent that.” In a creative industry that runs off the fumes of “inspo” siloed to oblique references, PHST dares you to come see where they live.

Get up close with the crew in our short film.

in your life?

in your life?