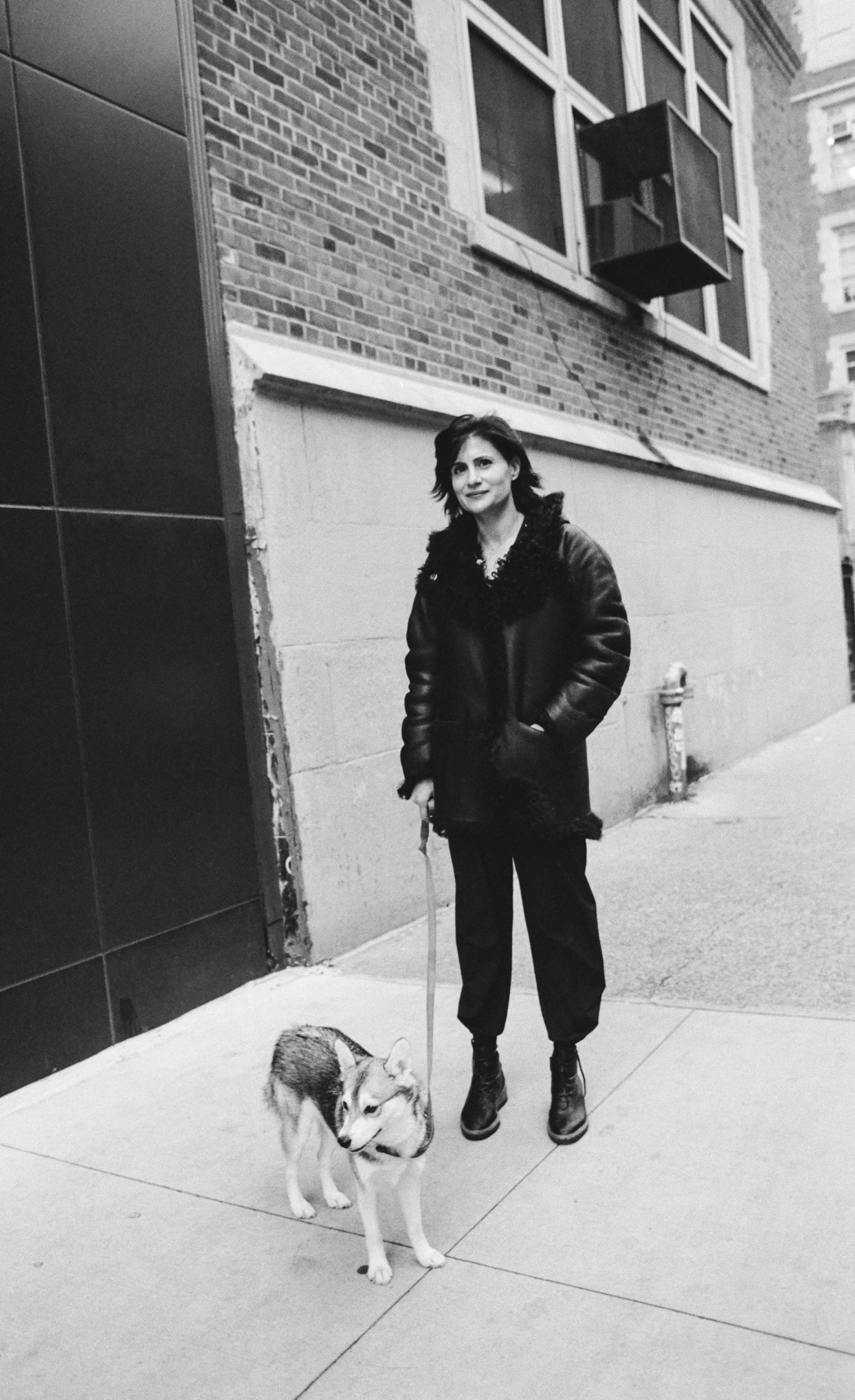

“Luna has made me see the city in an entirely new way,” remarks Amale Andraos as we depart from the bustling canine café Boris & Horton in the East Village. The nine-month-old Alaskan Klee Kai pup is a recent addition to the architect’s family. A dog was imperative to her kids’ supposed happiness and Andraos surrendered. It’s sweet justice; in 2003, when she and her newly-wed husband, Dan Wood, formed the architectural studio WORKac, their first project was a doghouse. Equipped with videos screening the pastoral, a treadmill and an odor machine, Villa Pup provided a city dog an immersive experience of the countryside.

Born in Beirut, schooled in Montreal and Cambridge (Massachusetts), incubated in Rotterdam and now rooted in New York City, Andraos has a cool unflappability that is enveloped by a passionate conviction for architecture’s possibilities. In 2011, she landed at Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP) as an assistant professor and in 2014 was appointed to the faculty committee to hire Dean Mark Wigley’s successor. Towards the end of the search, she threw her hat in the ring and became GSAPP’s first female dean.

During the first years of WORKac, the couple’s mantra was “say yes to everything”—that meant projects, competitions and teaching appointments. She became an academic by accident and her 2007 Princeton seminar on ecological urbanism resulted in the book 49 Cities (2009). Now in its third printing, the data visualization bestseller redraws visionary urban projects through an ecological lens, rating them according to density, green space, infrastructure and floor area ratio (FAR).

This through line—ecological systems in urbanism—led WORKac to their prescient design for the 2008 Young Architects Program’s MoMA PS1 commission. “Dan and I had just read Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma and this book brought together cities, farms, food and everyday life; it connected what is on your plate to the whole world,” Andraos shares. Their resourceful design for a biodegradable and recyclable cardboard-tube farm doubled as a canopy for PS1’s popular summer Warm Ups and shaded thousands during these Saturday music festivals. Public Farm 1 produced fifty varieties of organic fruits and vegetables and convened an assortment of characters. “We wanted to marry our new interest in food systems with the urban structures we studied for 49 Cities to see if we could build a piece of the illusory visionary city. It was a 150-person network of farmers, including graduates of the GreenHouse program on Rikers Island, chefs, artists, architecture students, solar panel installers and soil scientists.”

Admiring Public Farm 1’s exuberant combination of green ingenuity and a unique set of collaborators, Edible Schoolyard NYC approached WORKac to partner locally. Founded by Berkeley activist-chef Alice Waters, this twenty- year-old nonprofit has spread its edible education curriculum around the globe. Andraos immediately fell in love with the mission of introducing kids to issues about food and the city. Their first location, in 2010, was Gravesend, Brooklyn. The brightly-hued compound supports year-round farming (both outdoors and in a greenhouse), a tool shed, a kitchen classroom for thirty students and staff and a building shaped to collect rainwater for garden irrigation. Soon after, they established a second post for Edible Schoolyard in East Harlem.

Educational and community spaces are at the heart of WORKac’s roster of built work, and Kew Gardens Hills Library in Queens delivers on a decade-long saga filled with laughs, tears and a punch that was indicative of everything that could go wrong and did. Finally opening in 2017, the grass-roofed, low-slung building is abuzz with the diversity characteristic of this vibrant borough. WORKac’s resilience has been rewarded with a second library commission in Boulder, Colorado. The North Boulder branch will double down on eco-urbanism when it achieves its Net Zero designation (earned when the annual amount of energy used by a building is equal to the renewable energy created on the site).

Now in her sixth year as dean, Andraos wields and yields her authority with ease. Paola Antonelli, MoMA’s design guru, recalls, “GSAPP has traditionally been a place for cultural experiments and debate, but recently doors and minds have opened much wider—and fast! I remember that the first symposium of Amale’s tenure, on the Arab city, happened literally weeks after her appointment was announced. Clearly it had been in the works for several months, even before anybody thought Amale would be dean, and the effect was powerful. You could tell right away there was a new sheriff in town!” She has recast protocol and systems to reflect her values, hired and appointed women faculty to leadership positions and is adamant in amplifying female-owned practices. Her mandate to focus on climate action provides the foundation for the twelve programs she oversees, and the school performs as a loose organism, shapeshifting and responding to current events.

Last year, Andraos was tapped to design the Beirut Museum of Art. The commission is a homecoming of sorts, and a project steeped in history at an Arab center longing to be part of the international arts conversation. Beirut, like many global cities, has an unhealthy affection for glass towers, and the team prioritized preserving a sense of intimacy and scale appropriate for the site. The museum’s captivatingly playful façade is punctuated by dozens of lozenge-shaped balconies which, Andraos explains, “perform climatically, but are also beautiful transitional devices not only between inside and outside, but also between private and public space.”

Negotiating private and public space is exactly what Andraos and Luna do on their daily walks. Andraos reflects, “I’m always examining everything from various perspectives—an important part of designing for others—and I now find myself constantly rethinking the city’s architecture and infrastructure through Luna’s eyes; it’s so damn hard—and yet totally vibrant— being a dog! Imagining the world through Luna’s senses makes me think that humans really need something like a Villa Pup—an architecture that encourages us to simplify, get close to the ground and reconnect with the environment.”

in your life?

in your life?