The Chicago-born Matthew Williams, founder of the label 1017 ALYX 9SM, is an autodidact. He is a product of our culture of confluence, in which the boundaries between various cultural disciplines have been erased and the idea of creative genius has been replaced with the idea of creative multitasking. This has given rise to a new generation of designers who eschew the traditional design route of schooling and apprenticeship. They have supplanted the idea of elevating fashion into art with the aspiration simply to do cool things, reinterpreting their cultural influences through their own lens. This approach was formerly reserved for streetwear and other aspects of DIY culture, but by now streetwear has broken into fashion’s castle and routed its taffeta-clad troops. The hype-driven results aren’t always impressive, but what sets Williams apart from his peers is how far he has come from his days of making logoed T-shirts and hoodies. Alyx has grown into a full-fledged fashion brand with a clear-cut identity.

To be sure, Williams has had help along the way. It all started with his love of music, which led him to DJ when he was still in college in Los Angeles. He began meeting various music industry people at nightclubs. Parallel to DJing, he was also working as a production manager in fashion. Williams got his lucky break in 2008, when Kanye West’s stylist asked him to make a jacket for West’s Grammy performance with Daft Punk. The jacket had embedded LEDs that lit up on stage. West was impressed and asked Williams to come work for him. Williams, who was only twenty-one at the time, eventually went from making costumes for West to art directing his videos and setting up the studio for West’s first brand, Pastelle. At some point Williams met Lady Gaga, for whom he worked for three years. Through Lady Gaga he met photographer and later collaborator Nick Knight. And so on. As a result, it wasn’t hard for Williams, who seems affable and approachable, to build up an impressive list of friends and acquaintances in creative industries.

“In large part, I owe my success to all the people I met while working for Kanye and Gaga,” Williams tells me in a FaceTime interview. “I learned a lot just by watching others, by seeing the process of creation.” It was mid-March, and worldwide coronavirus panic was just beginning to take hold. Our originally in-person interview near Williams’s East Village studio now had to happen via video. Williams was at a friend’s house on Long Island, having escaped Italy with his family a couple of weeks prior, just as Milan was succumbing to the virus. (Little did we know that New York would become its next epicenter.)

Williams, along with Virgil Abloh and Heron Preston, formed the creative direction trio that crafted West’s image during the last decade. All three went on to found their own lines. Of the three, Abloh’s success has been the most meteoric, culminating in his post as the menswear designer at Louis Vuitton. It is Williams, however, who stands out in terms of his vision. He has successfully been able to transcend his streetwear beginnings into a style that marries techwear and tailoring into a hybrid that’s recognizably his own.

“Matthew Williams belongs to that lineage of designers who operate with the metropolitan background in mind. Helmut Lang was the forefather and the debt is evident, but Williams is no imitator,” critic Angelo Flaccavento tells me. “His way with sharp tailoring and decisive metal-ware is quite unique. He luxuriates in the hidden technicalities of clothes-making, which means he makes proper clothing, not silly stuff marketed as creation. This straightforwardness is what makes him a winner, to my eyes.”

Though we did not talk about it directly, I imagine Williams would have no qualms with recognizing his influences, whether Helmut Lang or Massimo Osti. What became immediately apparent during our interview is that Williams is a fashion fan par excellence. Our conversation veered off in various directions and quickly became an excited chat of two fashion nerds, in which Williams freely acknowledged the greatness of other designers, a refreshing sentiment in the often-catty fashion world.

The debt that Williams owes to his design forebears is not a bug but a feature. Indeed, as Flaccavento noted, while the design elements of Alyx may be familiar—techwear, bondage, minimalism—Williams combines them in a distinct way. “I think Matthew’s equal obsession with form and function is something that sets him apart; he has a very strong view on what the Alyx world should look and feel like, which I think is clear in how he’s built the communication of the brand, but he is just as focused on the product itself as he is on the image,” Sam Lobban, VP of Designer Ready-to-Wear and New Concepts at Nordstrom, who has invited Williams to produce a capsule collection for the store, tells me.

At the heart of Williams’s designs is a pair of juxtapositions—that of the masculine and the feminine, and the formal and the casual. Actually, these terms are becoming outmoded, and Williams is exactly the type of designer who is outmoding them by universalizing his garments. For example, looking at an Alyx coat, it is hard to say whether it’s dressy or casual because his fabrics tend to be both utilitarian and luxe. That a lot of the garments are rendered in black, a color that automatically lends clothing a degree of elegance, further liberates the wearer, letting he or she assign their own meaning to the clothes. “Partly, this philosophy came out of necessity,” says Williams. “We are still a small company, and we can’t really afford to make something that’s very specific, like eveningwear. So, we try to make garments that have a duality to them, like a five-pocket jean but from a tailoring fabric that can be part of a suit.”

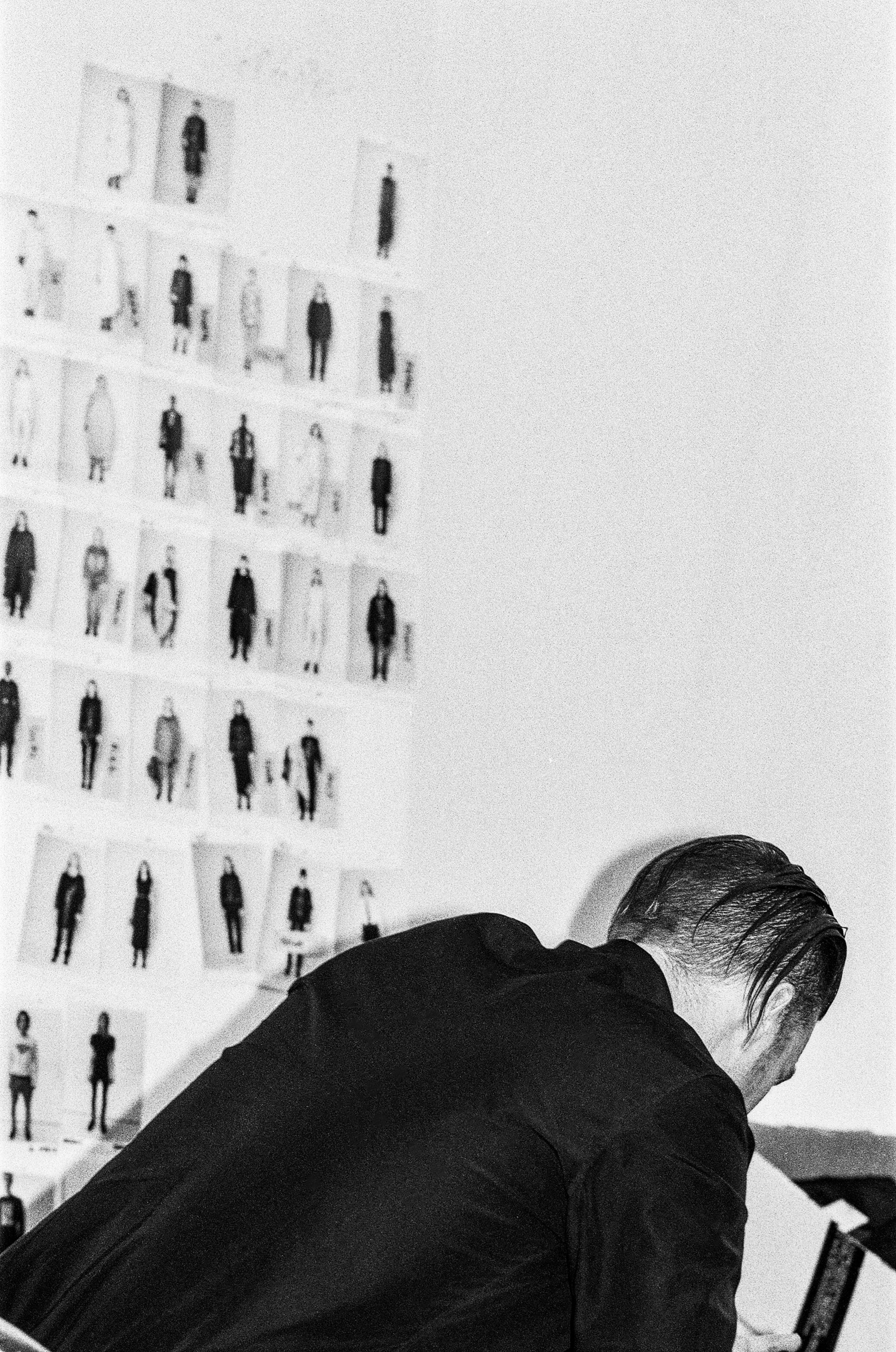

But while Williams has evolved Alyx into a legitimate fashion brand, he has kept that communal spirit that he developed during his years in the music industry, where collaboration has become a key practice. That family feeling was especially palpable at his Paris show last June. I have rarely seen the excitement, the sheer energy that many of his friends, famous or otherwise, brought to the show. It was an audience that cheered, unafraid to be impressionable, without the requisite jadedness that makes so many fashion shows feel listless.

Williams extends the same energy to his work via a multitude of collaborations with other brands, and not just the commercial giants like Nike and Moncler. It could be a heritage brand like Mackintosh or an artisanal, niche footwear maker like Guidi. If he loves what a brand does, he asks them to work together. “I like to approach labels that make a product that we cannot make ourselves, which also allows us to learn from them as a brand,” Williams tells me. “And we like to collaborate long-term, which lets us develop the product and take it to a new place.”

The latter two collabs, both with brands that do one thing extremely well, also come from Williams’s “product first” ethos. He’s not the type of designer to start each collection with a theme, cowboys one season and astronauts the next, nor is he interested in historical or futuristic explorations. “My clothes are always about the present,” he says. Instead, Alyx focuses on the elements of the garment itself, and Williams will happily go on about fabrics and construction methods, about marrying the technological advances in both to the appreciation of making things by hand—what he calls “modern craftsmanship.” You can see that approach in the clothes, the way they are obsessively constructed, the way each detail is carefully thought-out. “Whenever I speak to Matthew, he’s always talking about a new dyeing technique he’s working with someone on, or a new factory he’s found to develop his tailoring with, or about how the factories he’s been making the same product with for the past three or four seasons have finally perfected some detail to the level he was always hoping for—be it the pattern, a seam detail or some other intricate design element which pulls back to his core ideal of what Alyx really stands for,” says Lobban.

“Because I started as a production manager, I was first attracted to clothes-making, to how physical that was,” says Williams. You can see that physicality in Alyx’s most recognizable detail—the roller- coaster buckle—which aesthetically sits closer to industrial design than fashion. Unsurprisingly, the buckle is manufactured in Austria by a factory that produces auto parts.

Because Alyx is about building the modern wardrobe by wedding the elegant and the functional, while concentrating on the product itself, for Williams quality is paramount. By extension, to him quality means sustainability, because he builds products that last. In the world of corporate greenwashing, I found Williams’s view on sustainability refreshing. He’s an advocate of the less-but-better approach to fashion consumption. “At the end of the day, what will have to change is the consumer frame of mind to where they learn to buy less; that will be much more beneficial than anything I make,” says Williams.

Yet, if there is one underlying aspect to Alyx, it is the personal approach that Williams takes. “What I make is still basically defined by what I want to wear, not by what tradition dictates it should be,” he says. “I pull from what I find most interesting in clothes, and that makes the whole process emotional for me.”

in your life?

in your life?