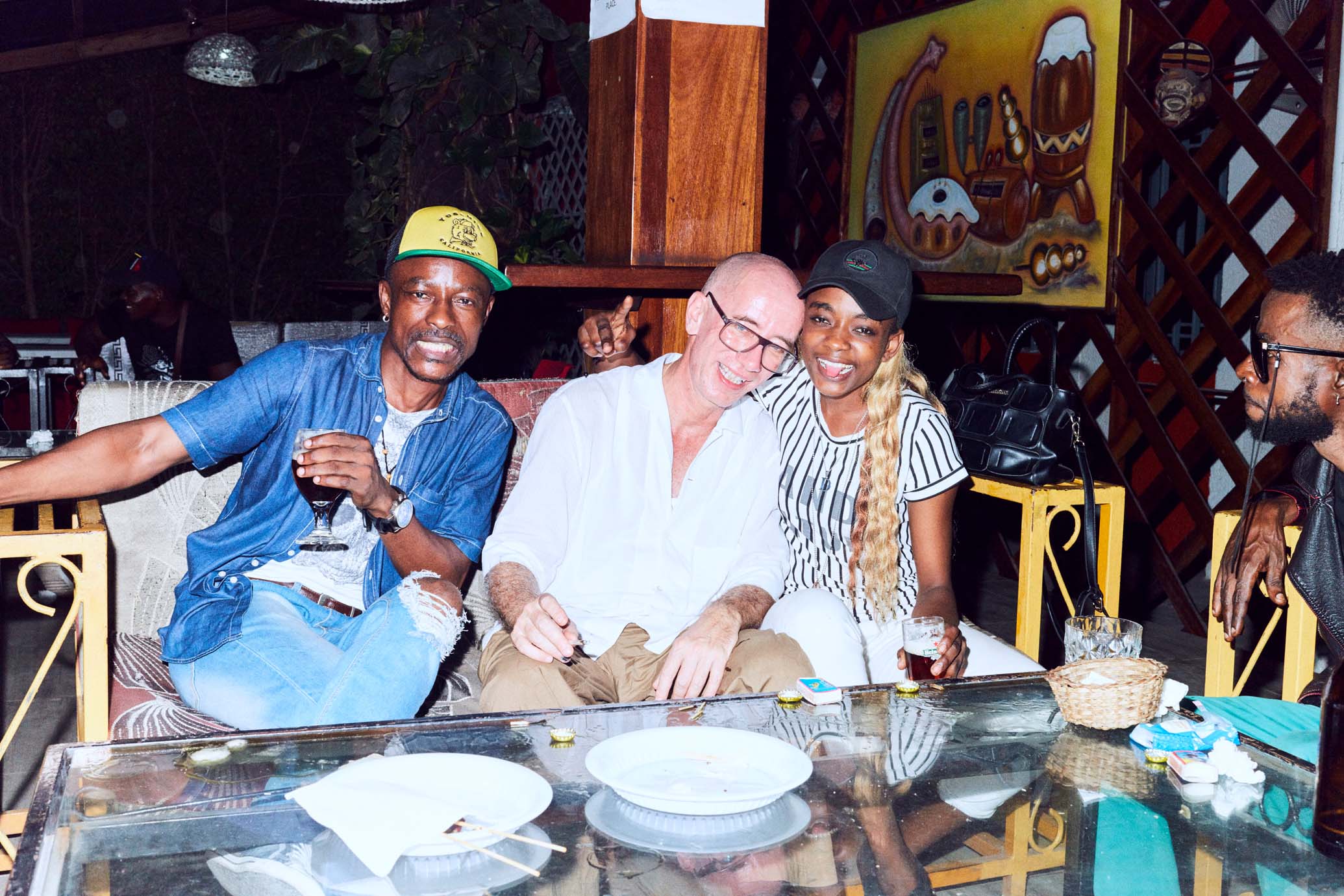

It's December 30th and Carsten Höller is in the Democratic Republic of the Congo describing a theater in Kinshasa while I pace around a friend's Manhattan living room trying to imagine the scene. There's no television in the apartment and I’m bad at visualizing physical spaces, so the image in my head proves to be inaccurate when Höller eventually shoots me an iPhone capture of an outdoor plaza which will, later that night, serve as both a movie theater and a stage for a set of three live musical acts.

Perhaps I am imagining something grander because my only touchstone for the DRC is Tram 83 by Fiston Mwanza Mujila in translation (I took and failed French) and Fara Fara, a two-channel mini-documentary following the titular Congolese music genre directed by Höller, which was shown in the 2014 Venice Biennale. I watched the documentary hunched over my laptop before the call. Even on my small screen, I understood the magnitude of Fara Fara’s local influence, which reaches beyond simply a pop genre and becomes a central social and political stage in the DRC.

This is perhaps the pull for Höller, whose work often revolves around a playful experimentation with social rules and the ways in which they are expressed by and manipulated through culture. The story is narrated as one of discovery: He came to the Congo on an informed whim in the early aughts, and returned for seconds and thirds and fourths of the musical scene he encountered on his inaugural trip. And then he felt he had to take it further.

“I just had this inner voice telling me to make it into a film,” he says of the impetus. The resulting film is just as serendipitous as his actual encounter. Fara Fara showcases a musical battle helmed by the late Papa Wemba, a god-like figure in the scene. It exhibits a tradition rife with dramatic flair, expert riffing and dueling dialectics; it's as if a contemporary opera guild were to marry improv troupe. The dialogue I'm able to understand proves to be unhelpful, as the scrolling translation is a storyline entirely fabricated by Höller, rather than a faithful dub of Papa Wemba or the other musician’s words. Holler is excited when we speak, as later that night will be the first time the piece will play to an audience able to understand both narratives in concert and contrast. He hopes that, by continuing to screen the piece, there will be a potential for the 13-minute short to become something larger. “I know that there is a feature film here,” Höller says. “I'm not sure I’ll be the one to make it, but the potential is there and I like to let it hang.” I think back to Mujila’s description of The Diva, the musically-talented love object of the main character. "[She] is like a witch. When she looks at you, not only are you unable to tolerate her gaze but you also feel like she’s acquainted with your life, that she’s more acquainted with it than you, that she knows how you’ll answer, with which baby-chick you slept last night, where and at what time you defecate, for which tourist you’re digging. It feels like she’s even influencing your answers.” Fara Fara has Höller under its spell for better or worse, and he might make me a convert yet.