In their debut solo exhibition, “Built to Scale” at Murmurs, Los Angeles artist Emily Barker offers a glimmering, surrealistic entry into an interior world. “Built to Scale” is an atmospheric installation of objects and light with a continuous soundtrack. Barker’s approach is as sharp as it is generous, commanding space to trouble ideas of disability and accessibility, reflecting the construction of both. In the artist’s words: “People do not yet realize that being ‘able-bodied’ is a temporary privilege.”

The only two-dimensional work in the exhibition is a mirrored wall text that verges on impossible to read. The words double and echo: “…Death by a million paper cuts. Imagine being loved. Imagine space being built for you. Imagine being a light to those around you. Imagine being a force to be reckoned with…” Barker certainly is. We spoke during the run of their exhibition.

Could you tell me about the show’s title, “Built to Scale”? This show is built to scale my daily experience for the able-bodied. It has been built to scale the feelings I have within environments designed for the “average person.” This is a forced perspective—one that comes across as being livable for everyone. I’m asking why and how we have decided upon what is standard, and wondering if people can understand that creating a standard means that someone like me who deviates from it is also oppressed by it.

Standardization is the effort to create larger profit margins, and to keep service cheap. Ramps are generally cheaper than lifts, but without proper mobility devices or help, I can’t use them, even though they are effectively built for me. Space is constructed toward an idea of what a person should be, not what they necessarily are. Even the idea of “access” is constructed by the able-bodied.

The kitchen, for instance, historically was standardized to the measurements of the average able-bodied man. It is replicated in factories at that scale as the cheapest means to install a kitchen by builders who are no longer skilled as carpenters. Before the 1950s, nearly everything was custom-built or customizable, and so older homes have varying countertop heights.

These are conceptual ideas about intimate space. Each piece in this show stems from a system forced on the abnormal, and each is an idea that is scalable.

Where did this project begin? What was the arch of these works coming to be? My collaborator Tomasz Jan Groza and I were looking to build a home that showcased solutions to some of these invisible concepts. We wanted to show that these are constructs that were created and that can change.

Everything that I do is the tip of a very large iceberg. I have relatively impractical ideas of what can be done within a certain budget and with my own physical capacity. The same goes for my writing and activism. This show is about the systems that prevent me from being able to actualize the reality that myself and others need to thrive.

I see this project as being much like the painted trope of interior spaces, like Van Gogh’s bedroom or Matisse’s L’Atelier Rouge (The Red Studio). This is the spirit of my environment, how I experience it daily. The soft light in the main gallery space mimics the lighting in my apartment. The hold tone of different insurance companies and doctors’ offices is endlessly playing in the background.

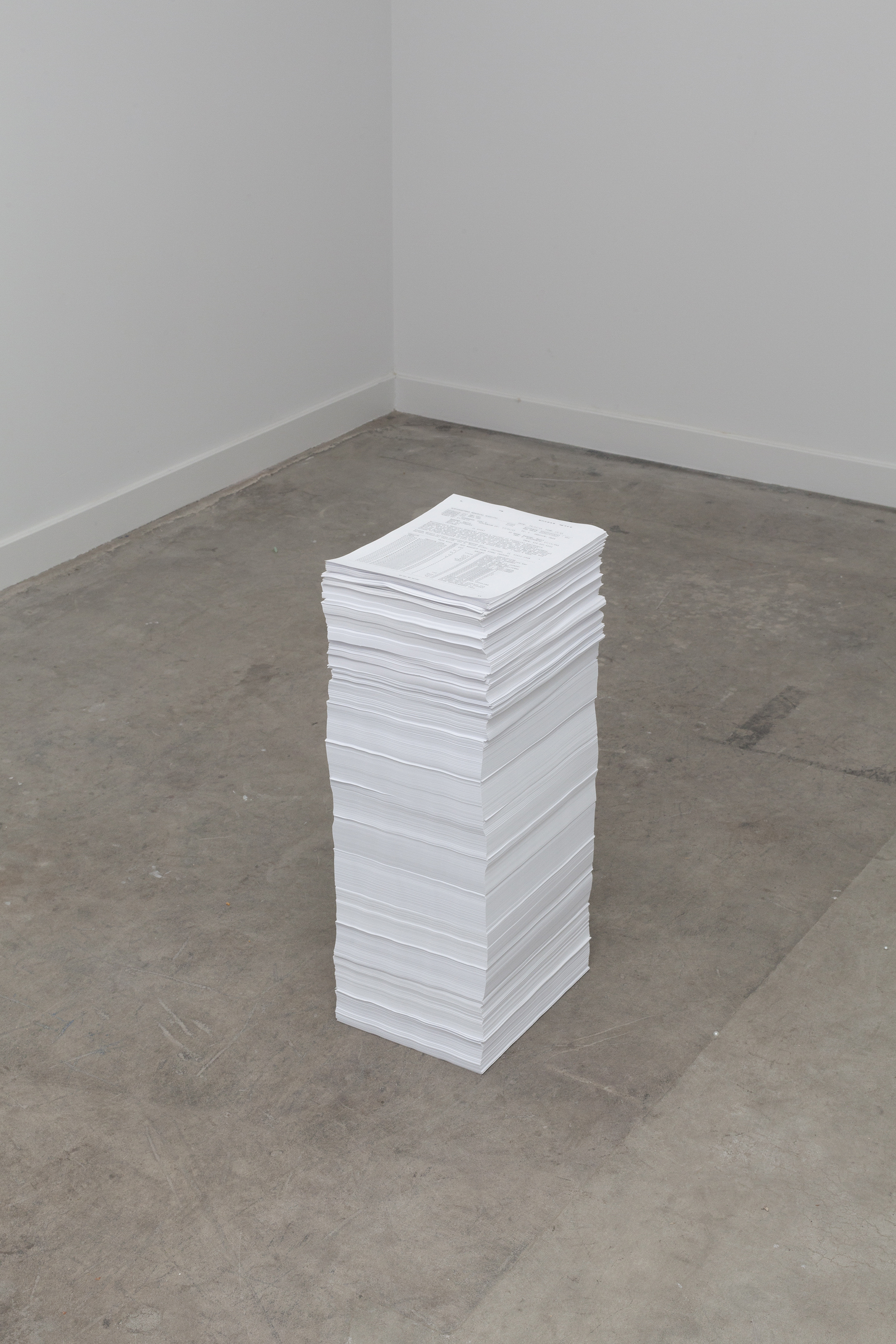

Most of my time is spent dealing with bureaucratic systems that grant me basic human needs. A stack of medical documents and bills takes up too big a space in an oppressively fluorescent-lit room. It’s a history of the labor that goes into navigating the bureaucracy, austerity and systems of eligibility of a healthcare industry that capitalizes off of horrible events beyond one’s control, while placing the blame back onto the individual. The first page is from the day after my accident and totals nearly $100,000 in spine surgery. This represents only three years of this type of billing and medical history. If I were to print out everything, the stack would fall over.

The kitchen is built to the surreal sculptural scale that I experience my own kitchen at. The ramp sculpture is excessively steep. I cannot move on any surface that isn’t hard and flat. Most people don’t know that a manual wheelchair becomes useless in grass, on sand, snow, dirt or on thick carpet. This show is really just a painting that I couldn’t paint because it wouldn’t give you the full scale of experience.

A lot of these objects and materials are translucent… I’m trying to be transparent. Translucent plastic is a stand-in for mass production: packaging, commodity, industrialization. It is ethereal and lightweight. The most common material used in the medical industry is plastic. My world is made of plastic.

The translucency also speaks to the invisible standards that make up our lives. My existence is heavily politicized, and people find ways to write these ideas off as “identity politics”—as if it’s not possible to have intelligent conversations about aesthetics, art, functionality, scale and plastic space as being in tangent with and related to each person’s consciousness and privilege. I do not need to compromise form and content to do so. My experience is not at all unique.

This show is for people who can stand and walk without mobility aids or having undergone dozens of surgeries. It is a glimpse into my experience. Most people cannot fathom the interior space of a home being so inaccessible, or ramps and wheelchairs not being the best solutions.

Built to Scale is a window into another world that enables someone to have an embodied proprioceptive experience of reality. This is a conversation about ways of seeing.

Could you speak about some of the materials used? They are highly textured—some suffused with a sense of violence or corrosion. The grabbers were cast, dipped in copper, and oxidized. The grabber is a material extension of my body, the only tool I have to navigate interior spaces. I hope that it will become a relic of an inaccessible world that will change. The iron oxide turns to rust when it meets oxygen, like blood turns red in an IV.

The arm is weighed down and eroded. My reality is violent. I am expected to take a submissive, appreciative role. What I say and how I act is policed daily. The night after my opening I was threatened with physical violence because I asked someone who was parked without a placard across three disabled parking spots to move.

The art market is just as violent. Most artists go without health insurance and proper compensation for their labor. On the other hand, art can be something so beautiful that it removes you from the mundane treachery of daily experience. But even this feeling is a luxury.

The butterfly night light is significant. Perhaps we can learn from its disturbing transformation from a caterpillar to a beautiful winged creature. It’s my hope that we can take what we have and make something more of it.

What’s behind the design of rug? The rug is made of 25,000 feet of IV tubing and was handmade by myself and my friends, which is how most good things in my life are accomplished. I’ve spent much of the past seven years hooked up to IVs, relying on them to save my life. Copper is a great conductor of heat and electricity, and it is found in bones. Here it brings warmth and contrast to the plastic. There is an iPhone headphone running through it that was trashed after getting caught in my wheels. And a doggy bag for dealing with shit, literally and figuratively.

How has your work in other forms interacted with or informed your artistic practice? It has all been a matter of convenience and communication. In previous years, having undergone 20-something surgeries and with many untreated illnesses, I could not have done what I have done this past year. What I need to say cannot be done through one platform only. I also use the algorithm (Instagram) to bring attention to these experiences. I wouldn’t say I do acting and modeling so much as I enjoy helping friends see their visions come to fruition and normalize my body. I would call all of this a form of community involvement, since it doesn’t pay and visibility hardly does much to change actual policies and standards.

Text is incredibly important and powerful. I do not particularly enjoy writing, talking or explaining myself. If I could, I would upload my experience and implant it into another person, although I would probably get sued for abuse. But at any moment you could be me. There is just so much to communicate, and words are a bridge.

in your life?

in your life?