I saw D'Angelo Lovell Williams's work in person for the first time this summer in Washington DC at Washington Project for the Arts (WPA), a small, non-profit art space founded in 1975.The young photographer was included in the two-person exhibition, “There Are No Shadows Here: The Perfect Moment at 30,” organized by artist-curator Tiona Nekkia McClodden, alongside the late photographer George Dureau. The show had been mounted on the occasion of the 30th Anniversary of WPA’s presentation of “Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment,” which the space had picked up in 1989 after the Corcoran Gallery of Art cancelled its slot in the exhibition’s tour for fear that Mapplethorpe’s photographs would disturb the Gallery’s ability to secure funding from the National Endowment for the Arts. It was, after all, the height of the now infamous “culture wars,” and debates surrounding the public exhibition of nudity, queerness, masculinity and flesh were at their peak.

Upon entering WPA, I was immediately drawn to a large self-portrait in which Williams is seated atop a hexagonal end table, covered in a cream fur throw. The artist, nude, holds a vase of flowers as two dying potted plants sit on either side of his feet. Positioned against a striking cerulean wall, you can almost feel the breeze gently giving what appears to be the living room curtains their slight motion. Williams’s gaze is directed squarely at the camera, but his look is less an invitation than a dare: I dare you to contend with this body, just as it is.

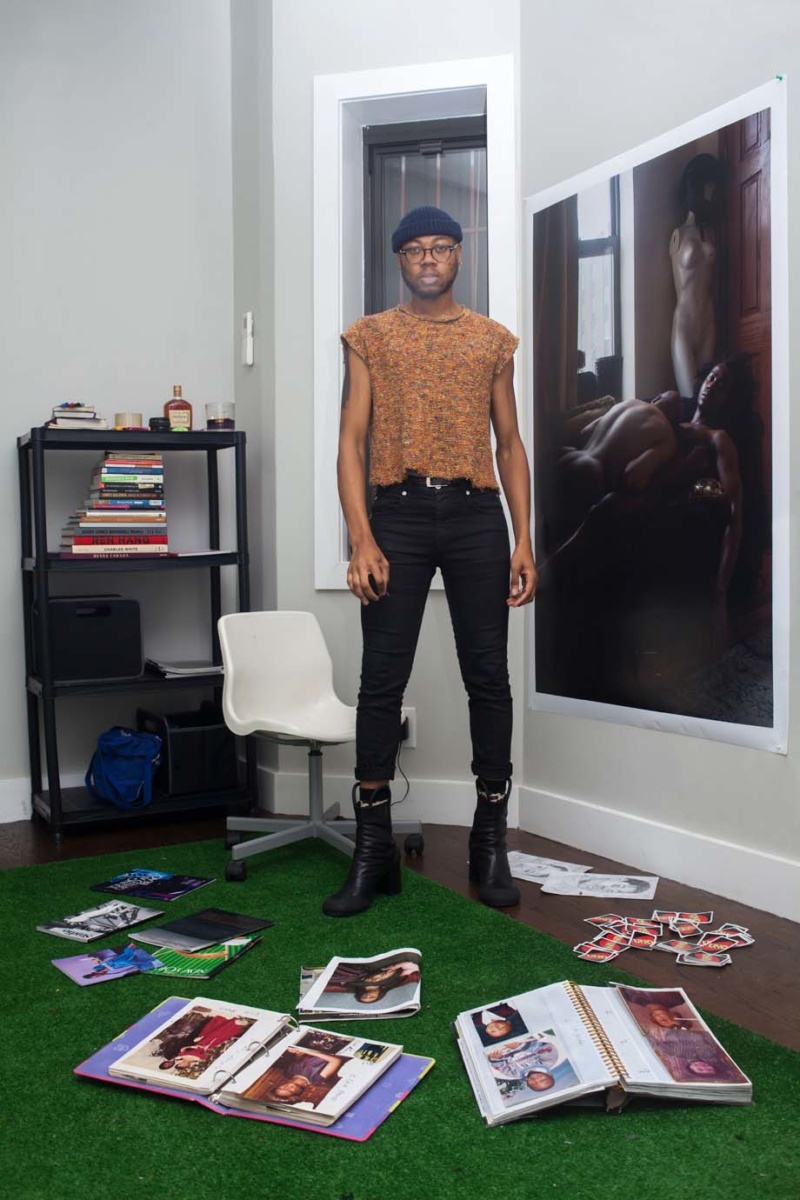

In addition to his presence at the WPA this summer, the Skowhegan alum has also exhibited with the New York City-based gallery Higher Pictures. “Extensions,” his most recent solo show consisted of six photographs in which Williams touches, entwines or poses in different capacities with other individuals. In this series, Williams’s keen interest in the hyperbolic becomes a prism through which intimacy is negotiated. We witness a photographer developing a vocabulary for the various ways in which he exists in relation to friends, siblings, parents and even lovers. In A Day Apart (2018), for example, the sitter wears a white lace dress underneath which another body protrudes, as if to evoke pregnancy. They are captured at night in a grassy field, the maternal representative holding the butt of a cigarette. In Burn One (2018), Williams is sitting behind another Black man on a staircase. The artist, while holding a blunt in his left hand, pulls at the skin surrounding the left eye of his companion. A mirror reflects the scene back at them.

Williams takes for granted the ability and desire to image those who look like him. In this way, these portraits and scenes are careful vignettes imbued with the language of representational politics that inform contemporary dialogue about photographing those who have been marked as “other.” Indeed, the discourse surrounding the ways in which the bodies of Black people—Black men, in particular—are imaged remains in a process of ongoing refinement and sharpening. What Williams brings to this conversation, the gesture to which I was lured that afternoon at WPA, is a precise choreography—one through which portraiture is a site for the meticulous unraveling of just what the body can and should do.