This past weekend in San Juan, the Antiguo Arsenal de la Marina Española building, one of the oldest structures in the Puerto Rican capital, came to life with the third edition of the MECA International Art Fair, where more than 30 exhibitors largely from New York, Puerto Rico and Latin America filled the space. Here’s a round-up of highlights from the increasingly popular contemporary art event, where the easy-going vibe on the island was felt all around even within the bustling fair environment.

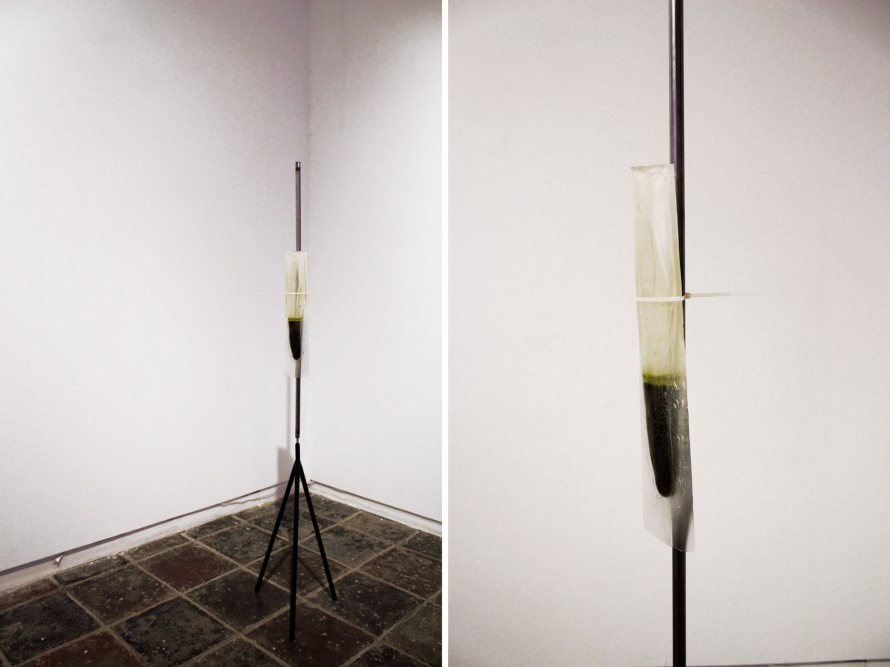

Sofia de Grenade's Prototipo de Aguilón (2019) at Sagrada Mercancía, Santiago, Chile The dark liquid encased in resin at the center of Chilean artist Sofia de Grenade’s Prototipo de Aguilón is eucalyptol—the chemical that gives eucalyptus trees their signature scent. It also happens to have the effect of making soil it comes into contact with toxic for other plants. In Latin America, where the tree was introduced by colonizers, it continues to grow across vast plantations that displace native forests. “It’s a very violent tree,” says gallerist Adolfo Bimer. “Because where you put eucalyptus, the soil gets so that you can only plant eucalyptus. It destroys all other flora.” The steel tripod-like structure on which the bag of eucalyptol hangs echoes a detail of a machine used to harvest the trees—as Bimer puts it, it evokes the “deforestation imaginary.”

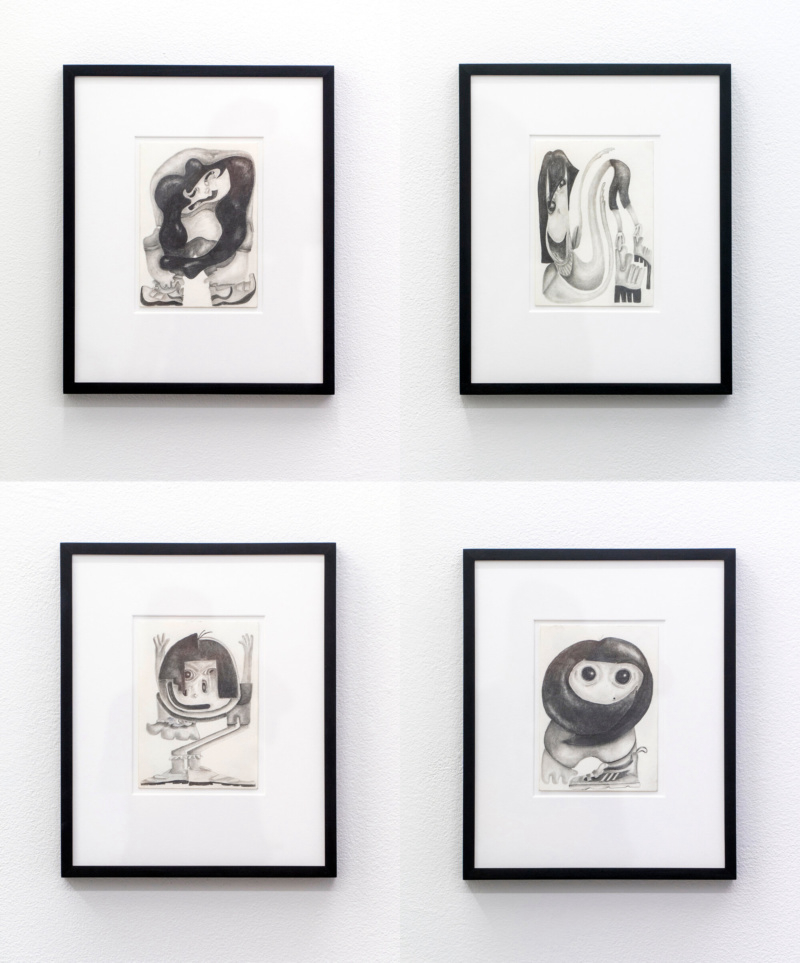

André Filipek-Magaña's Dora Drawing (Helsinki 1–4) (2019) at HOUSING, Brooklyn These four graphite drawings by California-born André Filipek-Magaña depict the popular children’s cartoon character Dora the Explorer distorted to varying degrees. The artist, who is of Mexican descent, reimagines the normally formulaic, amicable Dora alternatively as a geometric abstraction, a twisting, elongated swirl, a goggle-eyed, froggish creature, and a form that might be the result if Dora were a melting popsicle. HOUSING gallerist Shani Strand explains that the series “is supposed to reflect Dora as a mythic Mexican-American symbol. It’s not specifically speaking to Dora, obviously, but rather to this relationship of stretching and deranging and reconfiguring these concepts that we have: Dora as she relates to Mexican American-ness; to the fact that she’s this massive commodified image of Mexican-American-ness that’s entirely removed from Mexican-American-ness; to this commodified television educational series’s potential to speak Spanish—it’s inviting and introductory, but also exists within this completely removed state from the culture that it echoes.”

Ludovic Nkoth's Are We Home (2019) at East Projects, New York At only 25, the Cameroon-born, New York-based painter Ludovic Nkoth is shaping up to be an exceptional portraitist. Are We Home (2019) depicts his younger brother, Archie, on a red couch his family acquired after relocating to South Carolina when the artist was in his early teens. “We grew up on that red couch,” says Nkoth. However, the couch has since traveled back to a family property in Yaoundé, the Cameroonian capital, which he visited with Archie last year. “It was a weird place to see the couch because we’re used to seeing it here in the States,” he says. “I wanted to capture him in this space because we were home—but at times it felt like we were still visiting this place where we’re both from."

In the painting—the composition for which Nkoth assembled in equal parts from sketches, photos, memory and imagination—his brother bends awkwardly, as if struggling to find the once-familiar comfort of a now-unfamiliar seat. “That’s also why the character is a little uncomfortable,” says Nkoth, adding that he also means to tap into the lineage of “black bodies in alienating spaces. So that’s what I wanted to depict with this specific piece.”

Naimar Ramírez's Paper Bags series (2019) at Galería Petrus, San Juan, Puerto Rico

Artist Naimar Ramírez has a background in photography and architecture. “So paper—as a surface—for me has taken more importance as a medium, instead of something that holds images or whatever you decide to put on it,” she explains. For the past seven years, she has been experimenting with engraving faces, or “physical beings,” onto sheets of paper, which she does by strategically cutting strips and “building them up from the base material.”

“They’re all hand-sewn,” she adds. “The original series is called Máscaras o Más Caras—which literally translates into ‘masks or more faces.’ It’s a play on words but it’s also a play on how we present ourselves: a little bit of self-projection but also self-construction, through the intricate cuts and folds with which the masks are made.”

The use of paper bags in her nine pieces presented at MECA in part references “paper bag tests”—a racially discriminatory practice used in the early 20th century in which someone’s status would be determined by whether their skin tone was lighter or darker than a brown paper bag. In the context of branded shopping bags, “instead of skin color, it’s more about social standing,” says Ramírez. “You build yourself through what you buy and what you represent.”

Bailey Scieszka, Jar Jar Binks Boy Scout Painted Boy (2019) at Larrie, New York, New York

The paintings of Detroit-based Cooper Union grad Bailey Scieszka manifest a patchwork of bizarre internet conspiracy theories with which she is obsessed. For Jar Jar Binks Boy Scout Painted Boy, the artist borrowed the composition from an obscure mid-19th century portrait attributed to American artist Sheldon Peck. Built on top of this is a hodgepodge of references to a variety of both little-known and notorious online communities dedicated to substantiating far-flung beliefs: the inclusion of the iconic Star Wars character Jar Jar Binks, for instance, nods to concept that the world is controlled by lizard people, while a pair of preternaturally large blue eyes references the notion that Bratz dolls are not merely toys—but in fact true-to-life representations of actual people. “It’s like religion,” says gallerist Becky Elmquist on the conspiratorial ideas that inspire Scieszka. “Some people just choose to mask the truth by believing in something else.”

in your life?

in your life?