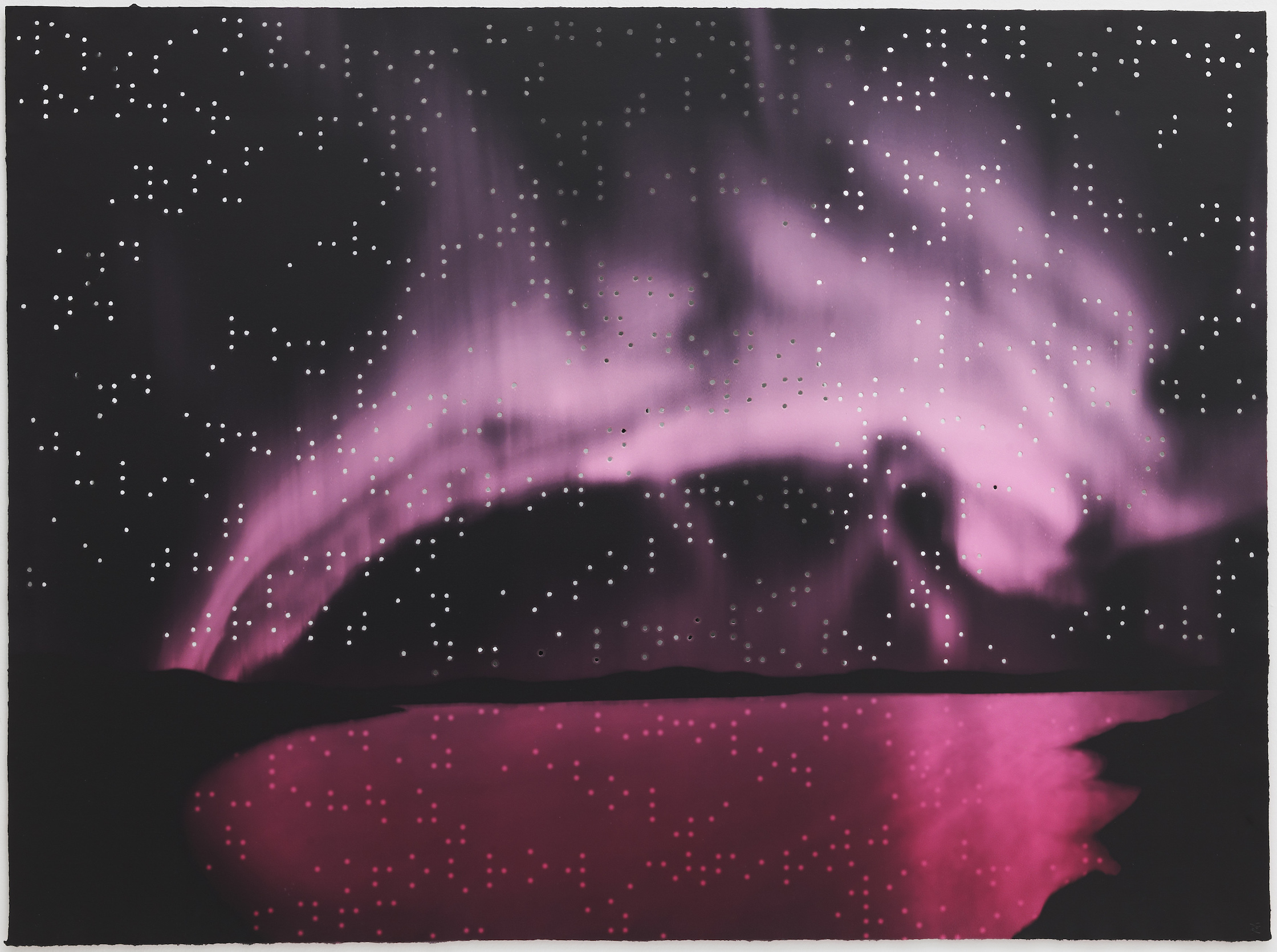

Teresita Fernández, like an alchemist or a spider, is known for how she transforms materials, weaves them into something great and bright. From her massive public installations to her smaller-scale sculptures, Fernández has turned the Blanton Museum of Art’s Rapoport Atrium into a swimming pool, spun silk into fire, and asked viewers, silently, to look for themselves in her landscapes—which might take the form of a sky studded with Braille stars (telling love stories), an iceberg on plexiglass, or a flame-engulfed field, made of dark ceramic.

"Teresita Fernández: Elemental"—co-curated by Franklin Sirmans, director of the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM), and Amada Cruz, formerly of the Phoenix Art Museum and the new director of the Seattle Art Museum—is a traveling mid-career survey, a first for Fernández, though it feels long overdue. The Miami-born, New York-based artist had her first solo show at Deitch Projects in the latter city in 1996; since then, she’s received a MacArthur Foundation Genius Grant, partnered with the Ford Foundation to create the U.S. Latinx Arts Futures Symposium, and, under Barack Obama, served as a presidential appointee to the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts.

Fernández’s work draws from the natural world, though in her hands, it becomes refracted and lambent, less simulacrum than experience. Her images of fire seem hot; her materials—onyx, glass, mirrors—earthen. Her world is dreamlike: the landscape rhetorical. Or its own kind of body. There are no figures but, she says, “I think of my work as thoroughly figurative in an almost traditional sense. The difference is, rather than painting or depicting a figure in a representative matter, you are the figure.” You might find your literal reflection in glass, or perhaps you’ll become immersed in the deliberately—manipulatively—subtle nature of her work. It prompts quietude, a pause, the other sort reflection. “Most people think of the landscape… as innocuous,” Fernández explains, “this passive work that you layer whatever you want onto it.”

Her idea of landscape is, in fact, “not passive at all. It’s very deliberate and strategized. Even our ideas about what places are—place names, borders and what’s visible—they’re such powerful tools to control how we think of ourselves in relation to land and to place.” For Fernández, there’s a poetic inverse to this idea: not only are we complicit in the inherent complexity of the landscape—intrinsic to it—we, too, hold landscapes in our bodies, the places we’ve been and all their narratives becoming a second set of eyes, a guide. She describes place as something you carry with you—its politics and manmade borders and strange phenomena. In light of “Elemental,” opening at PAMM this week, we discuss these ideas and more.

This exhibition is more of a retrospective, and in that sense it differs from your other shows. But you’ve said before that your process involves mining the site of your exhibition—not simply its physicality, but its mythos, the way it exists in the imagination. How might you be considering Miami in “Elemental”?

Although Miami is not the only venue for this show, I can speak to it, because the show changes from venue to venue. I have a different relationship to Miami; it’s the city where I grew up. Miami is just such a visually arresting place, in terms of light and saturated color, and this state of suspension where you’re surrounded by water and elevated bridges and pieces of solid ground. There’s a very surreal quality to Miami that you become extra aware of when you’re from there and don’t live there anymore. The landscape—the light, the color, the weather—is almost theatrical in that way. The sky will turn orange and then magenta. This doesn’t happen in Brooklyn, where I’ve lived for 20-something years.

The show isn’t just a reaction to Miami because it’s being held in a museum there, but because that landscape is in me, too, and a great part of the way I see the world—I like to think of it as not just putting the exhibition in Miami, but rather that the landscape lives inside of me, socially and politically, and certainly visually and optically, in a palpable way.

I love that you’ve described the sky, sunsets, and what happens here as “theatrical.” You talked about the theater of nature in an interview with The Brooklyn Rail, too. In Miami, you can’t get away from the theater that is nature. You live very much among it. I was walking today and crossed paths with a flock of ibis.

Yes! The publication that accompanies the exhibition, too, is worth mentioning. A lot was put into the exhibition catalogue, and there’s a revealing interview in it. I discuss both bigger ideas in my work that have to do with figures and landscape, and a very personal view of Miami specifically, what it was like to grow up there. I wanted to use the catalogue as a kind of document of the work being in Miami, and to tell the narrative from a very intimate point of view.

I haven’t lived there in 20-something years, and there are other places in the world that have been really important to me—like Japan, Cuba, places in Latin America and the Caribbean. So there’s no pat answer to the question, “What was it like growing up in Miami?” It’s really not that binary; the narrative is much more complex. There are all these places that hold and occupy a particular, intimate place in your relationship to place, because you’ve spent time in them during different parts of your life. Miami is one of those for me. But so is Japan. So is Rome. So is Cuba. So are parts of the Yucatán. It’s not just the place you’re from, because that’s the easy narrative. You’re actually from a lot of places, sometimes.

I’m thinking about Fire (America) 5 when I ask this. The landscape depicted in that work is affected by violence, both among people and within the landscape itself. In the multiple meanings found in your work, can one also find hope? Can that fire be renewing and cleansing, too?

The first way I’d answer this is actually by going back to show’s title: “Elemental.” I grew to love that word, because it suggests both the material and everything around it. “Elemental” means the powers of nature: atmospheric, environmental. But it also means essential—the raw core of something that can’t be reduced. The word encompasses the physicality of natural elements themselves—fire, water, earth—but also the hidden, underlying core of a substance, which is more elusive. It’s this quality that’s harder to pinpoint or to name; it’s so often rendered invisible on purpose.

I was intrigued by how “elemental” is often used with the word “force.” It’s verb-like, this impulse: fusing materiality with purpose. It’s not a passive word. Fire fits into that line of thinking. One of the interesting things about the exhibition in Miami is that I’ve taken these existing works and set them up in a way that’s like an installation, creating something new. Rather than just putting up these pieces as individual artworks in a survey fashion, I’ve created a landscape made of many other landscapes.

There’s one room that’s actually all about fire as an image. In some iterations, it’s more direct. The glazed ceramic series—of which Fire is a part—is interesting because of that glossy surface; you see your own reflection in the fire and in the darkness. That’s a really important component. Most people don’t think of my work as being figurative, because there are no “figures” in it, but I think of my work as thoroughly figurative in an almost traditional sense. The difference is, rather than painting or depicting a figure in a representative matter, you are the figure. You are the elusive figure that is prompted by the work to always find yourself within this landscape, which [in the case of Fire] is a very beautiful image, but also a very violent one.

I liked your question very much—about how the piece might represent hope. I think the essential component of renewal and redemption in those images—which are about the violence of the landscape—hinges on finding yourself in that landscape. That connects to a notion very essential to my thinking, which is that you’re trying to figure out what landscape allows, or what my use of landscape is—defining who you are in relation to where you are. When you do that, you can then understand who you are in relation to other people. This is a big part of understanding landscape as not just what’s in front of your eyes, but as the history of human beings, the history of power, the history of the lack of power. That, I think, is where the hope lies: the idea that you are seeing yourself in something that is not you, which is a pretty powerful notion.

I don’t think it’s possible to find one single thread connecting everything in “Elemental,” but in what ways are the pieces communicating with each other? In what other instances will viewers be implicated in the work?

When you enter the exhibition, it’s almost like you’re traversing a landscape. I don’t want to describe that in a literal way, but there’s a kind of way-finding to the show. At every turn, you’re actually being prompted on where to go next and how to move through these things. Many of the works have reflective or transparent elements, so you’re navigating the space created by these different pieces installed alongside and in relation to one another. There are a lot of pieces you walk under or through, or that you look down into, where you’re constantly seeing your own reflection. There are a few installations in darker rooms that you walk into as isolated experiences.

So you can’t traverse this exhibition passively. You, the participant, become very involved.

That’s the idea. In my work, that’s actually very subtle. It’s not an obvious cajoling into this or that. The prompting is very quiet, but it’s not passive. The quiet and subtle can seem passive. That’s how most people actually think of the landscape—this innocuous, passive work that you layer whatever you want on it. Nobody is threatened by this notion of landscape. That’s a very western point of view—humans always dominating the landscape.

I’m trying to invert that, because I think that what I’m referring to as the landscape—which is really inclusive and far-reaching, and includes the cosmos and history and an anthropological component—is not passive at all. It’s deliberate and strategized, and sort of manipulated. Even our ideas about what places are—place names, borders and what’s visible—they’re such powerful tools to control how we think of ourselves in relation to land and to place. I’m thinking about all of those things. There’s never a choice between this beautiful, experiential, sensual thing and social, political references. I refuse to divorce them or think of them as separate. They’re very much inherent in one another.

The quietness of your work is radical, in that way. Are you familiar with the practice of deep mapping? I think of it whenever I think of your work—mapping a place not simply based on its subjective topography, but on folklore, memory, movement, bodies.

I’m familiar with deep mapping, and there’s an aspect of what I’m doing that is very much about that, although I arrived at it from a different place. I don’t call it “deep mapping,” because for me it’s such a personal revelation—developing a way of working for decades that actually is what you’re talking about. But it’s very different to call it that and to actually create a practice around that. So I don’t use that word, but I think there are some interesting components. This idea that bodies are part of the landscape is a really good question, because that is very much at the heart of what I’m trying to do. Physical bodies are part of the landscape.

But maybe it’s about changing the word “body” to something with more depth, such as “individuals”—individual human beings. It’s important that that’s not general. I’m not really interested in a general viewer, or in bodies as these sort of floating things. I’m interested in intimacy that’s viewer-driven, and in the specificity of it. That’s why the work is quiet, because what’s happening—when it does happen—is on an intimate scale, and that means it’s very powerful, or that it can be. But it’s not always visible, because it’s happening somehow internally.

I’ve often talked about this: as the viewer being both a spectator and a performer complicit in this, and the kind of engagement that’s slow and quiet, but with enough depth that you recall it after the work’s no longer in front of you. Even when I make big public artworks, I’m interested in the public as being a bunch of individuals. Each individual is its own public, rather than this generic “public.” We know, clearly, that some people are never accounted for in that summation of what the public is.

Teresita Fernández: Elemental is on view at the Pérez Art Museum Miami from October 18, 2019 through February 9, 2020.