Leonora Carrington is often categorized as a Surrealist, but the label was bestowed by association rather than any adherence to the movement: the painter, sculptor, and writer launched her career in 1930s Paris, as Max Ernst’s much-younger lover and a friend of other Surrealist bigwigs like André Breton and Marcel Duchamp. But in spite of the otherworldliness of her paintings, which have a penchant for chimeras, underworlds, pagan rituals, and the occult, Carrington rejected the epithet—along with any critical efforts to get the artist to explain her works. “I am as mysterious to myself as I am to others,” she once claimed.

In Leonora Carrington: The Story of the Last Egg, on view through June 29 at 926 Madison Avenue in New York, Gallery Wendi Norris has approached the enigmatic artist through the lens of activism and eco-feminism. The third solo show organized by the gallery, comprising over 20 paintings and six sculptures, the title refers to a play Carrington wrote in 1970 that was to be produced as a stage production until funding difficulties forced the project to be abandoned. Opus Siniestrus: The Story of the Last Egg is set in an apocalyptic world where all women have died off except for one: an obese octogenarian ex-madam who, as per the show’s press release, “gains possession of the last surviving human egg, and holds the fate of the planet in her hands.”

The egg is a recurring trope throughout the works on view, the central figure around which the show is organized. An image of life, fertility, and the feminine, the egg takes on a darker symbolism here, representing both humanity and the planet as endangered species struggling to survive in the wake of World War II. As gallery director Matea Fish explains it, the egg was “Carrington’s preferred metaphor for a world ravaged by patriarchal systems of violence, war, and ecological destruction.”

Born in Lancashire, England in 1917, Carrington encountered forms of this violence firsthand. In 1939, Ernst was detained by the German army in Paris and sent to a concentration camp. The distraught Carrington fled to Spain, suffered a psychotic break, and was committed by her parents to a sanatorium, where she was held against her will for about a year. Her treatment there—which included electroshock therapy and a cocktail of mind-numbing drugs—became the traumatic inspiration for much of her subsequent work. Once rescued from the Spanish asylum by her former nanny, she managed to flee Europe through the help of Pablo Picasso, who helped arrange a brief marriage of convenience between Carrington and his friend Renato Leduc, a Mexican ambassador, with whom Carrington spent a period during the 1960s in New York before returning to Mexico. She lived there with Emerico Weisz, her second husband, and their children, creating art until her death in 2011.

The exhibition meanders chronologically through Carrington’s life. The earliest work is the iconic Down Below (1941), which, like her 1943 memoir of the same name, grapples with her experience in the asylum. It was in the book Down Below that Carrington began to sketch out the theory of the egg: “The egg is the macrocosm and the microcosm, the dividing line between the Big and the Small,” she wrote. In the painting, there are no eggs, but five human-like figures and a horse are staged against the verdant background of a Spanish landscape. The woman on the right, whose face most closely resembles Carrington’s own, frowns languidly as her body appears to transform into a butterfly. In the center, a buxom vamp with the head of a goat lounges in a bustier and red stockings. She looks like a Baphomet, a mythical chimera incarnating the totality of all binaries—good and evil, male and female. She holds a white mask in her hand and leans on a bearded lady, behind whom sit a green Medusa and a glowing white naked woman with the face of the bird. Whether the women can be considered five incarnations of the artist, or just a menagerie of mythical figures—of which Carrington is said to have had an encyclopedic knowledge—Down Below is seminal, as Fish explains, because it marks the “new world view” the artist began to forge during her time in the sanatorium.

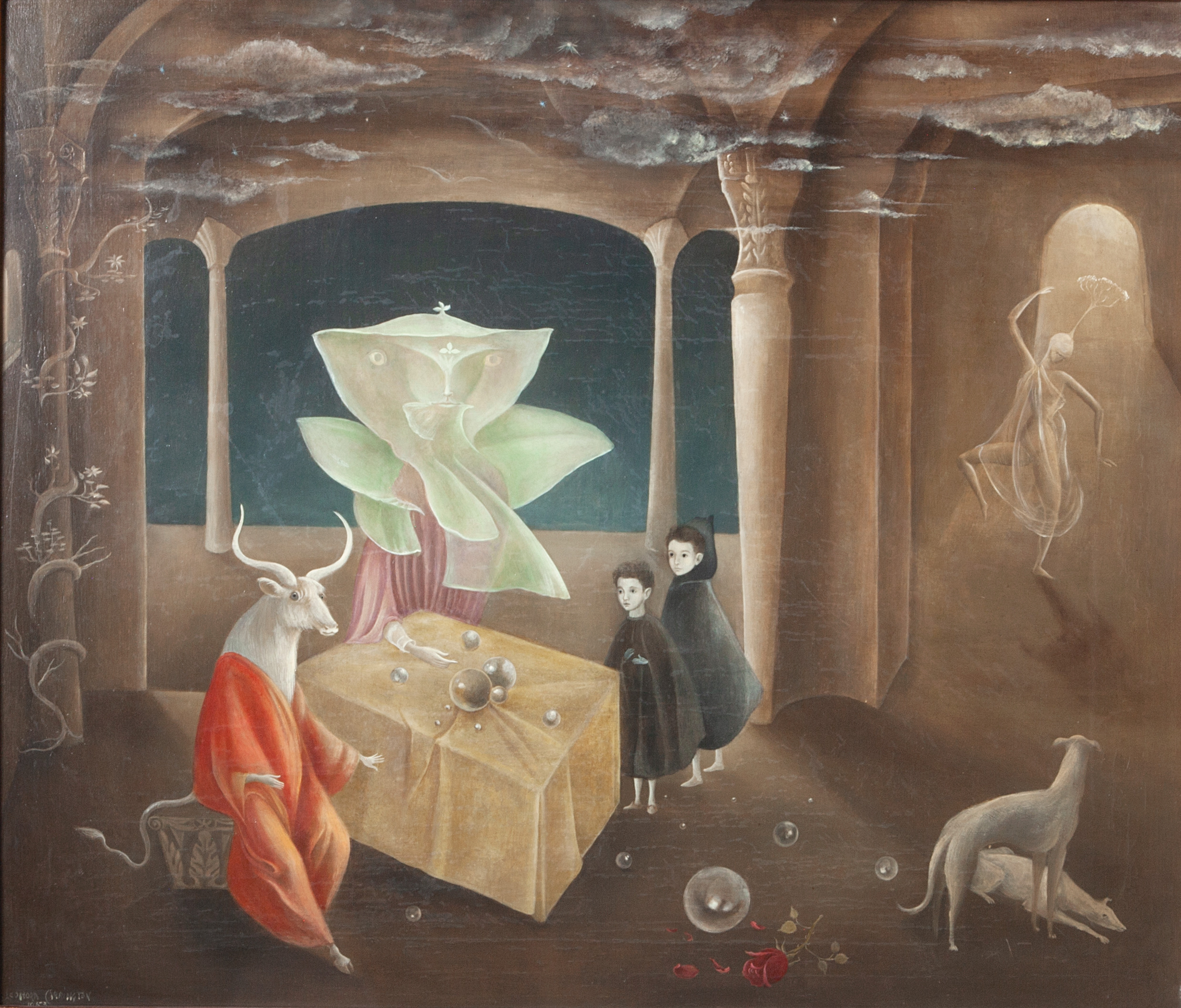

The exhibition’s second phase explores Carrington’s time in Mexico and is presented as the period of her “eco-feminist” awakening. This was apparently inspired by her encounter with Robert Graves’s 1948 book, The White Goddess: A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth, which traced global religions back to a common matriarch. This is the White Goddess, a sort of Earth Mother, and Graves’s text sought to demonstrate that this figure ceased to be worshipped because she was obliterated by patriarchal structures and ultimately replaced by a singular male deity. It’s in these paintings that Carrington began to depict literal eggs, along with representations of the White Goddess. And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur! (1953) is considered by many scholars to be a sort of family portrait. The painting features two cloak-clad boys—probably Carrington’s sons—along with a minotaur in an orange robe, and an iteration of the White Goddess. These four characters surround a ceremonial table off which glowing orbs are tumbling. In the corner, a white whippet is the only creature in the work to notice a dancing ghostlike figure bathed in light.

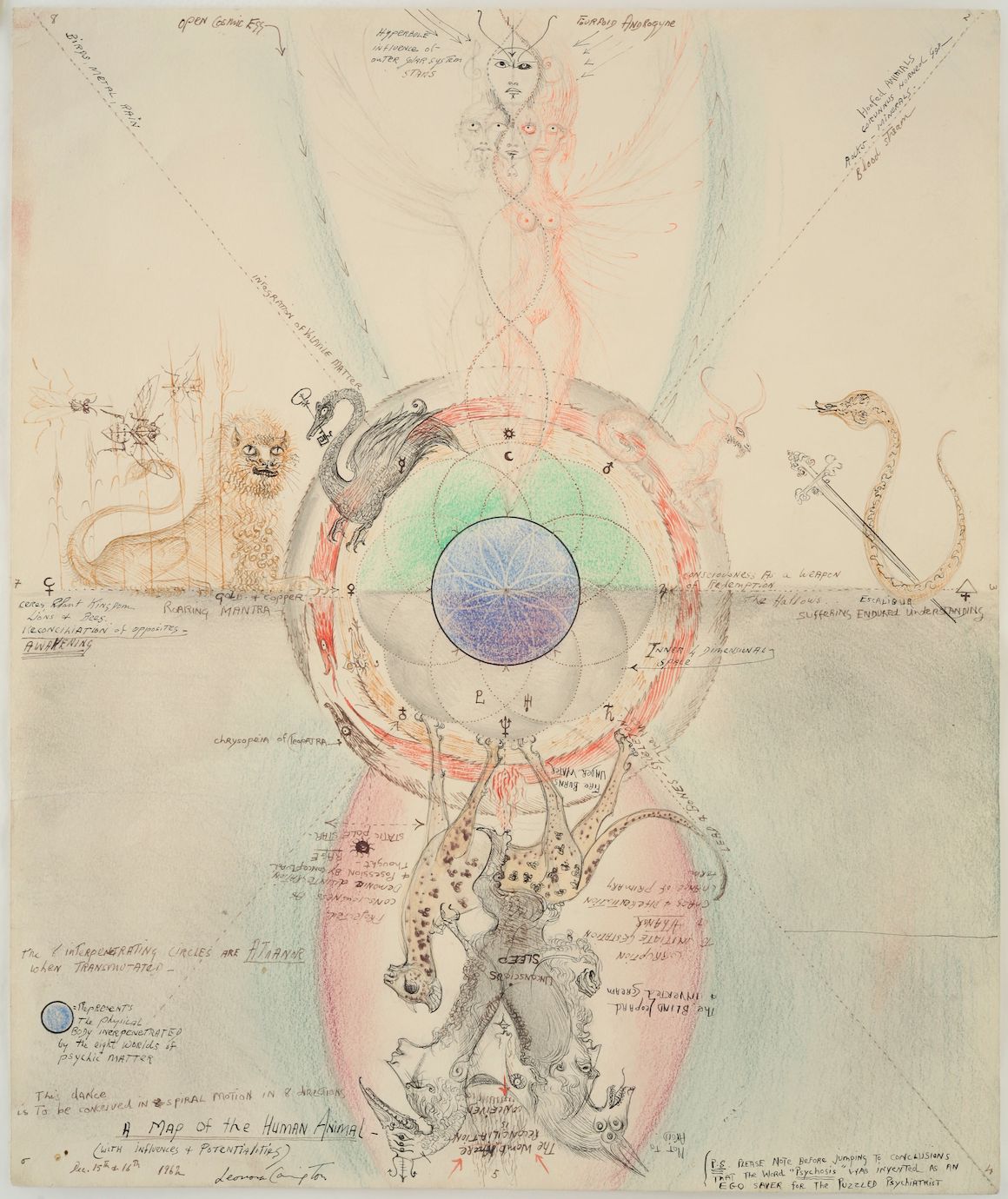

The third part of the show treats Carrington’s “activist” phase of the 1960s and ’70s. The gallery was able to track down the original Mujeres Consciencia painting (1972)—the basis for the iconic poster of the Women’s Liberation Movement in Mexico, which Carrington co-founded. Throughout these works, we see that for Carrington, in keeping with the times, the personal was political. And in keeping with her egg theory, the macro was the micro, and the universal the individual. Nowhere is this clearer than in her Map of the Human Animal, painted over two days in 1962, which serves as a blueprint of human consciousness. It centers around an athanor ensnared by an infinity chain of snakes feathered in the style of Quetzalcoatl and surrounded by the 12 zodiac signs, along with several other chimerical creatures. In the bottom right corner is a note in which Carrington anticipates her critics’ judgment of her own sanity: “P.S. Please note before jumping to conclusions that the word ‘psychosis’ was invented as an ego-saver for the puzzled psychiatrist.”

It was in 1965 that Carrington first painted the vision that would become the subject of her unrealized play. Untitled (Preliminary Sketch for the Opus Siniestrus) (1965) sketches out a pagan ritual around a cauldron in which Adam and Eve sit, surrounded by cannibals and godlike creatures. A second version of the scene is titled Sinister Work (1973), and replaces Adam and Eve with Hitler, Nixon, Superman, and Hopalong Cassidy. The change essentially creates a continuous line between original sin and its contemporary iterations during Carrington’s time. The reason for this plot change might be elucidated staged at the gallery on June 6 at 7:30pm, when a dramatic reading of the Opus Siniestrus will be staged.

With Hilma af Klint having broken records at the Guggenheim, the timing is propitious for another retrospective of an overlooked female artist with occult inclinations. And with a biopic on Carrington forthcoming from Lena Vurma and Thorsten Klein, Carrington’s works are sure to see an increase in value among collectors. As to whether the exhibition is inspired by eco-feminism or data-driven art capitalism (Wendi Norris is a self-described “data junkie” and former tech entrepreneur)—maybe it’s both, in an echo of Carrington’s favorite axiom: “As above, so below.”

Leonora Carrington: The Story of the Last Egg is on view at Gallery Wendi Norris through June 29, 2019.

in your life?

in your life?