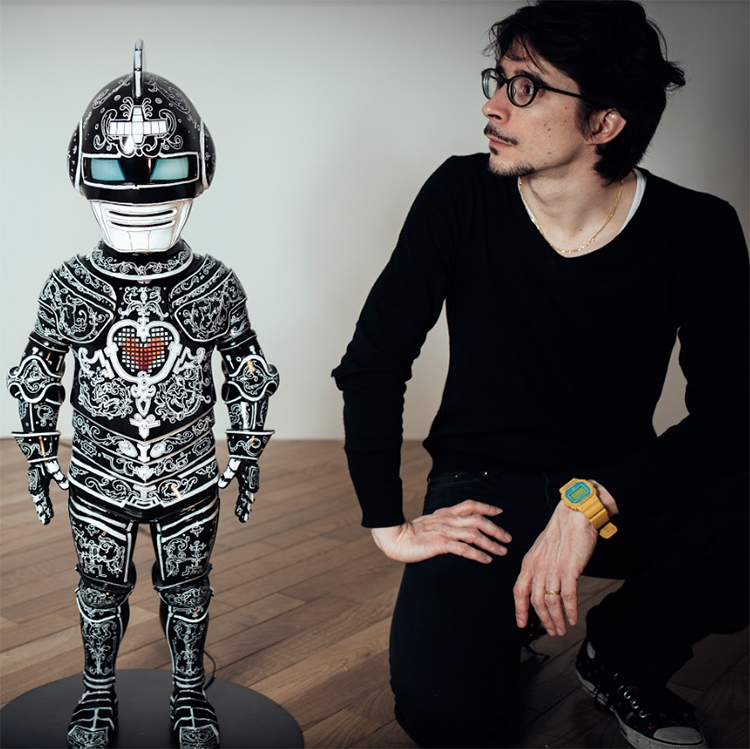

French-born, Tokyo-based artist Nicolas Buffe debuted in the US this past spring with the opening in the Miami Design District of “Serious Play,” one of five facades comprising the Museum Garage project. Buffe’s four fantastical twenty-three-foot caryatids flank the garage’s entrances and exits. This work, like others, combines his fascination with video games, French and Italian Baroque ornament, and Japanese anime and manga culture. His art has been exhibited in Maison Rouge, Paris, and the Museum of Contemporary Art and Hara Museum in Tokyo. He has collaborated with Commes des Garcons and Hermes on fashion projects and designed theater and opera sets. Here, he chats with Cathy Leff about his own mash-up visual language.

CL: How did you become interested in Japanese culture? NB: As a young boy, I was completely obsessed with Japanese animation. Japanse TV series with superheroes and special effects were my favorites and popular then in France. I especially liked Spectreman, a kind of Planet of the Apes remake with the superhero fighting bad gorillas that were attacking Earth. There was so much Japanese animation available on TV. I was watching feature length animation. I didn’t even realize at time it was Japanese. It just seemed part of my everyday life and culture. When I would draw, I would make my own superheroes, similar to another Japanese one, Space Sheriff Gavan, who was a robot-like man who could switch suits in a second to take flight. He was my childhood superhero. I also was always playing video games, normal for a child in France at the time.

What was your formal art training? The moment I became conscious I had an interest in art, I went to L’Ecole des beaux arts. There was lots of pressure there. Being in a school surrounded by 400 plus years of French history was very impressive. Then there was the Louvre, across the river, looking back on you. I felt the weight of history and the weight of my peers and professors. I had a sort of crisis, since I wondered if my fascination with cartoons and animation were a legitimate pursuit. I questioned it I should throw away all the things I loved and grew up with? Then I said to myself, I would create art I care about from my interest in popular culture and the childhood things I liked, but also my interest in history. I began to construct a personal way of looking at history and my place it. I didn’t think I belonged to any current contemporary way of thinking about art. I built my own family of art.

Did your professors encourage you to pursue that path? Yes, they were very encouraging. It wasn’t like Les Miserables or Cinderella. It was just a way to construct my universe and my history. I remember maybe it was Basquiat who was building his own imaginary ancestral history going back to the dinosaurs. I had my own way of doing it with my own taste, going back each century and looking at ornament. I love the grotesque and artists who can work across disciplines. One day they write a text, then create a sculpture, then make a painting. I never put limits on my practice nor placed boundaries between art, design, and architecture. I also love video games as an art form. Denying video as an art form is like living at beginning of 20th century and saying cinema isn’t art. My work leaves doors open for many audiences to enter the work. I first try inspire awe and then more serious probing.

Do people need to understand all of your references? My art derives from popular culture and philosophy. I try to create and solve a puzzle in each piece. The more educated the viewer, the more they understand the references. However, the notion of game—to play—is a big part of my work. I try to get you to unravel the clues. I call my work “serious games” because I’m always mixing up things and trying to put together things that don’t seem to have anything in common. My work is a network in time and space—sort of like space travel.

What are you working on now? Video games. It’s ongoing work and I don’t know exactly when it will launch. I’m working with a French TV channel, Arte, who produce cultural projects. Recently, they started to produce video games and web content. Mine is a video game for a gaming device. The theme is one I have been working on for many years, the dream of Poliphilo, a Renaissance romance story. Poliphilo falls in love with Polia, but she doesn’t love him. In his dreams, he goes through many adventures looking for her. Everything is allegorical. The original book was published in 1499, in Venice. It then was very avant garde. There are cryptographic drawings in the book, with many meanings and codings. It’s close to a video game, with many clues within. I first saw it when at L’ecole des beaux arts. No one is sure who wrote this book—maybe a group of people, but all the ideas in it are very humanist. The French edition had a tremendous influence on French art. For example, Louis XIV’s Gardens of Versailles are a kind of game of Poliphilo.

You’ve now lived in Japan for many years. How do you identify culturally? I learned a lot of things from Japanese and French culture. My PhD thesis was about mixing different cultures. I am a French man who has been Japonized. I have a lot of Japonese inferences in my behavior. It takes a different energy to dive in to a new culture. The Japanese are super protective, shy, and don’t understand why we’re interested in them. I’m almost like a one of my superheroes. I took off from France and landed in Tokyo.