“I painted a lot of angels back there,” the late artist Purvis Young once said, in an interview. “God sends angels to try to clear up some of this trouble on Earth. I don't listen to the Man, I look up to heaven. It's a habit I got.”

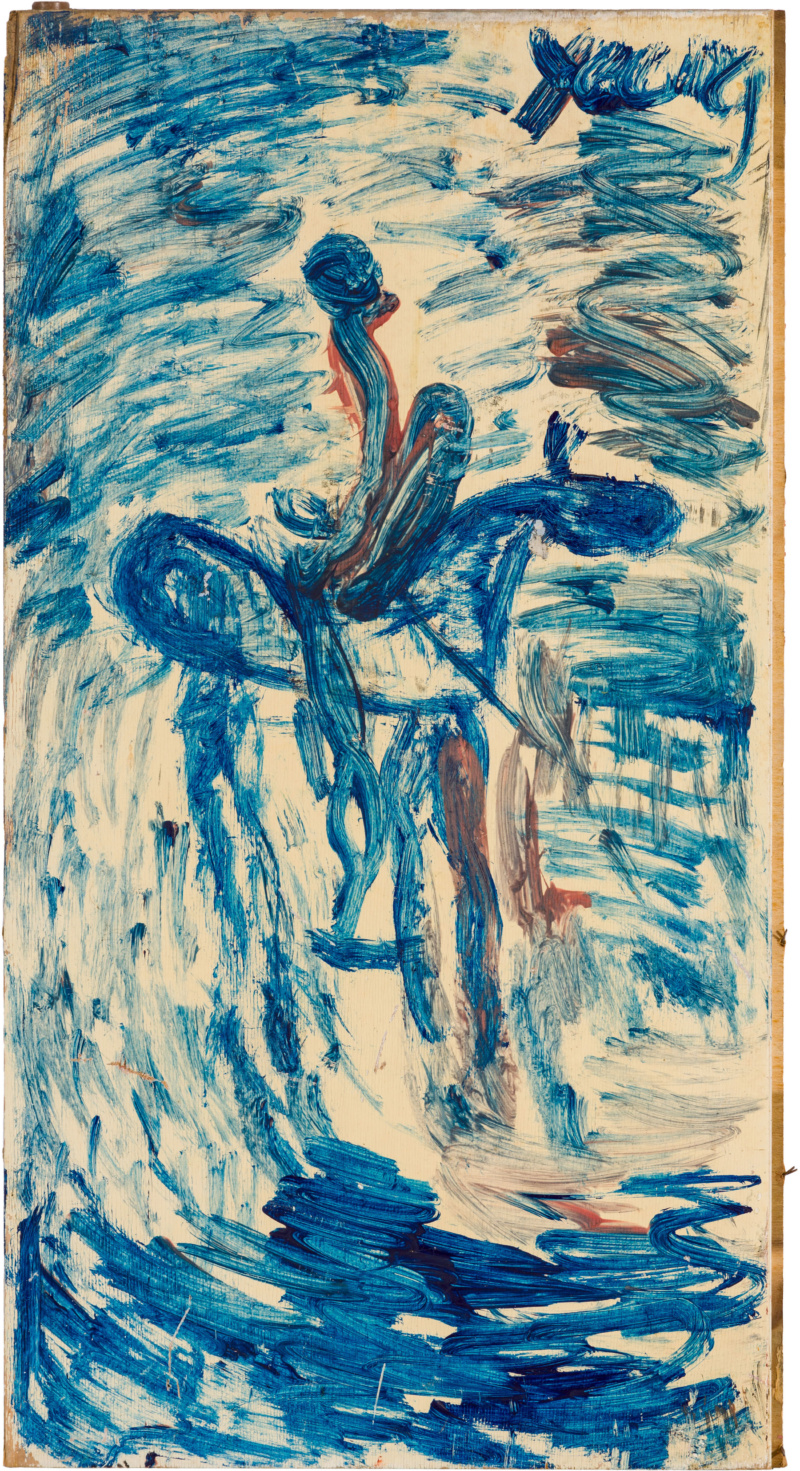

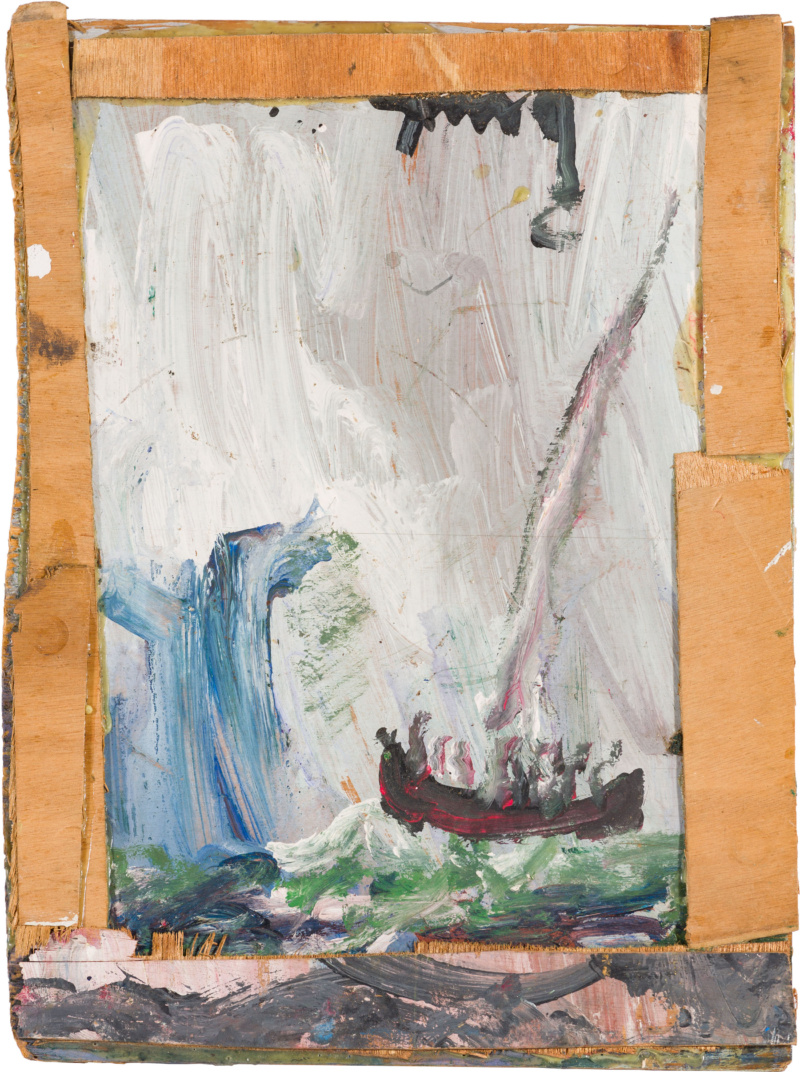

Young was born on February 4, 1943 in Liberty City, Miami. After drawing as a child, he finally began painting in the early 1970s—he'd just moved to Miami’s Overtown neighborhood and was interested in the mural movements of other cities. He painted walls, hunks of wood, pieces of detritus he found on the street; his work was vibrant and moving, and depicted an entire, self-created coded language: angels (God), horses (freedom). Black figures, haloes. Water. The push-and-pull between heaven and hell, both of which, sometimes, were here on earth.

The painter depicted the conflicts of his day, and those that came before—the latter end of the the Vietnam War, the Great Depression, the oppression of Native American and black families in the United States, poverty—and the brightness of hope, too: the kindness of strangers, the power of faith, the healing qualities of art. He painted dreams and struggles, protests and prayers. He studied the work of Vincent Van Gogh, Rembrandt, El Greco, Picasso; his work is not unlike a hybrid of Abstract Expressionism and Impressionism. He began to sell his paintings, often to white tourists.

Bernard Davis, then the owner of the Miami Art Museum, eventually became a patron of Young’s. In 1999, so did the Rubell family, purchasing the entirety of Young’s studio (nearly 3,000 pieces) and later donating pieces to institutions around the country. Late last year, during Miami Art Week, the Rubell Family Collection Contemporary Arts Foundation opened Purvis Young, a floor-sized exhibition of Young's work. Still on view through June, the show includes over 100 of Young’s paintings, each from the permanent collection. (A few were recently received as a donation, in memory of Janet Fleisher).

The work is striking: Young began painting so shortly after the Civil Rights Movement and American antiwar protests; he lived in Overtown just 15 years after the passing of the Interstate Highway Act, which confirmed the construction of a highway in the midst of Overtown and displaced countless black residents from their own community. Though the artist passed away in 2010, his work grows more timely today.

We spoke with Juan Roselione-Valadez, Director of the Rubell Family Collection, to learn more about Young’s legacy and the effect it had on the Rubells.

How did Don and Mera Rubell meet Purvis? I know they eventually bought all of his works. In 1998, the Rubells were at dinner at the home of their friends, the Antonis, in Miami. The Antonis own a painting by Young, and Don and Mera were intrigued with the work. Also at the dinner was Tamara Hendershot, who was a gallerist and a close friend of Young’s. Tamara and her collaborater, Jeffrey Knapp, a poet and professor at Florida International University, arranged a studio visit shortly thereafter.

Young had already discussed with Tamara and Jeffrey his desire for the Rubells to acquire the entirety of his studio prior to their visit, and once all were at the studio, he shared this with the Rubells. Young said his landlord was threatening to evict him and to destroy the thousands of his paintings in his studio. The Rubells spent the day with Young, viewing and discussing his paintings and his plans for the future. Ultimately, and after speaking with their son, Jason, and daughter, Jennifer, they agreed to purchase the contents of his studio and to donate many of the paintings to institutions around the country.

Since then we’ve donated 494 paintings to 18 museums and universities. I can’t imagine that many museums or private collections would make a commitment on this scale—acquiring and assuming responsibility for the care of 3,300 paintings.

Young was influenced by artists like Vincent van Gogh and El Greco, by Impressionism and a language of motifs all his own. He is arguably one of the greats. How is the art world attempting to "classify" him, historically? Classifying artists is convenient but problematic. When white artists educate themselves they’re often referred to as “autodidacts.” When black artists educate themselves they’re referred to as “self-taught,” “folk artists” or “outsider artists.” Young is also referred to as an “urban artist” with urban being code for black and, perhaps, poor. Young educated himself via public libraries, public television and public radio and managed to achieve something that any artist can tell you is nearly impossible: to dedicate his life to his work and support himself solely via the sale of his paintings. His interest in art history also extended to modern and contemporary artists, such as the COBRA group and the artists that created Chicago’s Wall of Respect mural.

Tell me about the current exhibition itself, the shared trajectories and periods in Young’s life. The exhibition’s bookends are birth and death, with a suggestion of an afterlife. It’s the largest single artist presentation we’ve made in the foundation’s 25-year history. I’m outside as much as possible studying birds, plants and fish and I rely heavily on field guides, so I felt a field guide of sorts was needed for Young. This was after seeing his work erroneously titled at other institutions and a general sense that the frenetic nature of his painting led many to ignore the content therein.

We’ve parsed Young’s work and highlighted many of the concerns closest to his heart, presenting each in a separate room. These themes include institutionalized racism, mass incarceration, the refugee crises, the drug epidemic—basically everything that still rends society apart a decade after Young’s death. Artists spend their entire life grasping for meaningful content and imagery, but with Young’s first forays into art, his murals/protests in the early 1970s, he created a repository of images that he would draw from and expand upon for the rest of his life.

Of the works, are there any that move you in particular? There’s a haunting painting of shackled slaves hovering above the ocean, gulls flying in the distance, the ocean’s waves are highlighted with red paint, and angels are between the slaves’ legs, preventing them from drowning. Perhaps when Young made this painting he had recently read or heard accounts of slavers drowning their captive men, women and children, at times by tying them to the anchor’s chain. The Martinique poet and politician Aimé Césaire wrote an equally haunting and horrific poem about these practices.

Last year, Young was inducted into the Florida Artists Hall of Fame. Do you have any insight into his rising popularity? It only seems sudden. Recognition for him is long overdue. What amazes me is the sheer number of people who own an original painting or drawing of his, more so than perhaps any other contemporary artist, not just in Miami but nationally and internationally. The German painter George Baselitz collects his work, as does the musician David Byrne, but so do schoolteachers and librarians and anyone who knew him or knew of him, often through word of mouth.

For many, Young’s paintings, loaded with his social and political concerns, were the first, and perhaps only, original artwork in their home. Young was accessible, often painting outside along busy thoroughfares, and he always made the work available. A large painting of Young’s was recently exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art as part of a show highlighting new acquisitions. How often can you stand in front of a painting at the Met and, at the same time, for better or for worse, scan sites like eBay or Etsy on your phone and purchase an original painting by the same artist for under $1,000?

In 2008 we included Young’s paintings in a group exhibition, 30 Americans, that has since traveled to 14 museums. It’s currently on view at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, and from there will be presented at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City and at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia.

Purvis Young is on view at the Rubell Family Collection Contemporary Arts Foundation through June 29, 2019.