Earlier this year, artist and pedagogue Adelita Husni-Bey’s site-specific installation Chiron opened at the New Museum, spotlighting a group of protagonists in the global immigration crisis. “There is no law to save most people,” one of the haunting first lines of the exhibition’s namesake film Chiron (2019) rings out into the cavernous, blue-lit gallery. Voices continue, projecting a mixture of frustration and compassion regarding immigration policy in the United States. “We’re having to prove that these places are bad and that we’re good in order to win,” says a pragmatic young man. “We’re perpetuating… the myth that we’re the savior.”

Curated by Helga Christoffersen, the site-specific installation is Husni-Bey’s first institutional solo presentation in New York and includes three video works. Postcards from the Desert Island (2010–11) shows students in an experimental French elementary school grappling with self-governance and models of organization in a Lord of the Flies-like environment. The two-channel video installation 2265 (2015) was created with members of Authoring Action—a group of teenage authors led by Nathan Ross Freeman—and shows the teens exploring the possibilities of populating Mars and the resulting capitalist colonialist structures produced from occupying new territory. Chiron features lawyers from the pro-bono New York law firm UnLocal, Inc., who outline their fight for the rights of undocumented immigrants and their families within the United States legal system.

Husni-Bey’s longstanding interest in how societies organize politically through the law becomes evident through the mingling voices of weary lawyers, precocious teens, and sing-song students. Within the exhibition, the viewer is overwhelmed with questions about the origin of rules and their arbitrary enforcement. These queries manifest in a sea of floor-to-ceiling banners that glow with text written in UV-sensitive white ink—excerpts of United States immigration law from c. 1882–2017. Spanning more than a century, the laws provide historical context for those discussed in Chiron, employing viewers to consider how different groups of people came to the United States and who has historically benefited from the country’s legal system upon entry.

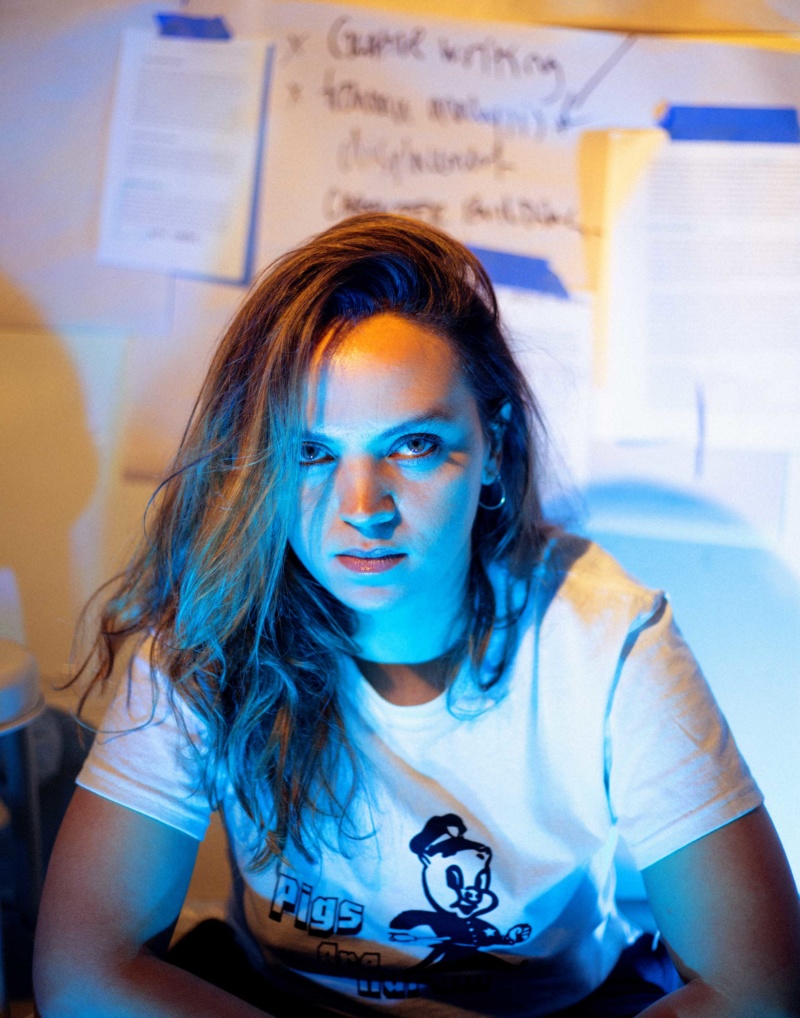

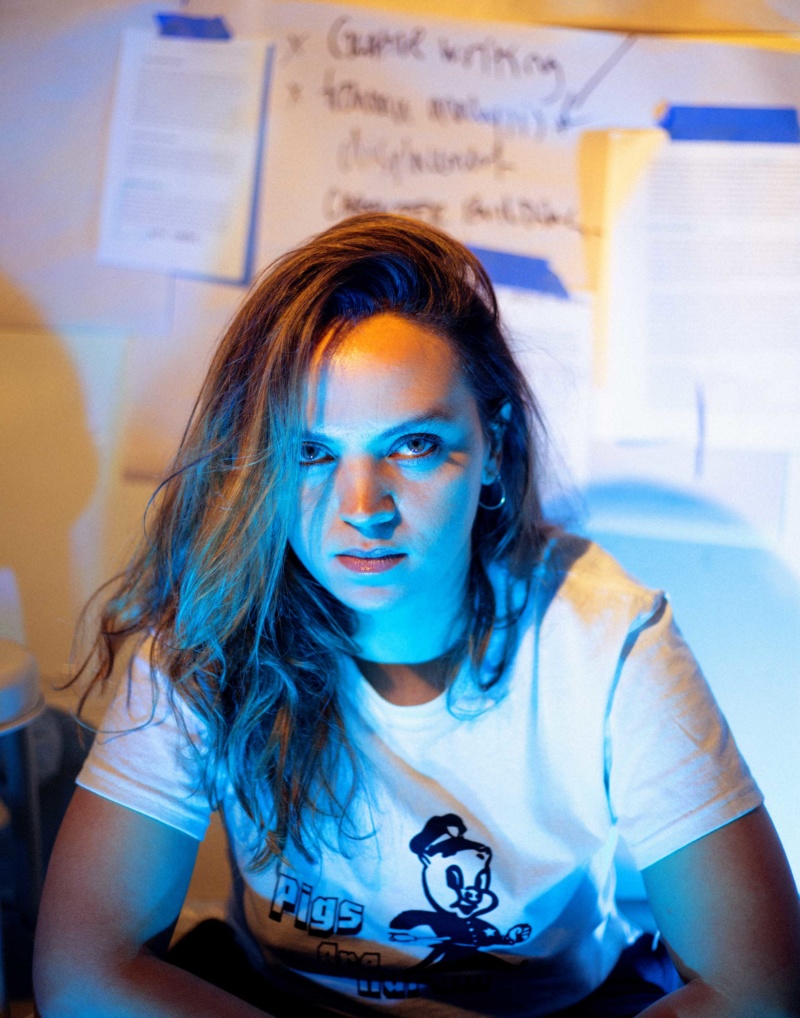

Born in Milan, having studied in London, and now living in New York, the topics Husni-Bey addresses are rooted in personal experience: “I think ‘displacement’ would be too strong a word for me,” she explains, “but I certainly moved a lot between Libya, Italy and the UK, and had the capacity and privilege to do that… to forge community.” Perhaps due to this, most of Husni-Bey’s projects begin with collectivity, employing collaborative pedagogical models in a workshop setting to produce and record material. In this way, she has created photo essays, radio broadcasts, publications, and archives that form the foundation of her film work—which has been included in the Venice Biennale, where she represented Italy in 2017, and in “Being: New Photography 2018” at the Museum of Modern Art.

The making of Chiron also began in 2017 when Raoul Anchondo and Christhian Diaz, board members from UnLocal, asked Husni-Bey if she would be interested in developing a workshop for their organization. The exhibition takes its title from the Greek mythological figure Chiron, an immortal centaur who is notable for being an intelligent and nurturing educator and natural healer. Ironically, Chiron eventually does succumb to death, a healer who could not heal himself.

While working with UnLocal, the term “secondary trauma” became a touchstone of conversations. “Secondary trauma, or as I prefer to call it, after Sara Ahmed, ‘emotional depletion’ happens when the work you do to change the institution becomes overwhelming,” Husni-Bey explains. “It takes a toll on your person, on your body, somatically. It’s often associated with activism or social work.”

Husni-Bey’s workshop with the law firm examines this trauma through the lens of American policies around immigration. Chiron, subsequently, is about how the constant struggle to fight systemic oppression generated by the United States legal system leaves a wide array of communities with exhausted leaders, healers who have no time to heal themselves.

The film also does well to address the seemingly arbitrary application of legal protection and the disadvantages faced by many immigrants who have already made it to the United States and made the country their home. There is a chilling moment when, in the mundane setting of an office conference room, fluorescent lights humming, one lawyer recalls the government’s threat that offering legal aid to undocumented immigrants in order to procure documentation could potentially qualify as aiding and abetting a criminal.

In Chiron, Husni-Bey reemphasizes the brutality of borders, but she also focuses on a seldom-talked about piece of the current global immigration crisis: the broader effect a broken legal system has on communities working within the law. We are asked to consider our own protection under the law in relation to others, and why this is. With this understanding, only then can we begin to collectively heal.

in your life?

in your life?