As an artist working in both photography and sculpture, Leslie Hewitt situates herself in what she calls the “liminal space” between the two. It’s a comfortable positioning where she can be attuned to what the disciplines of photography and sculpture grant her as she creates her work. “I am attracted to being here physically,” she shares with me as we sit in her Harlem office on bright summer afternoon as she prepares for her September solo show at Perrotin in Paris and her presentation at the Carnegie International, opening October 13. “Sculpture never has to argue that point; it is not an illusion. It is here with you,” she continues. If sculpture allows Hewitt to assert a physical presence, then photography provides her with an opportunity to consider temporality. The photograph is both the object and the conduit; it tugs at the elasticity and fragility of time. “Photography gives a little bit more because it is not just the now, it is also what just was or sometimes what was even further back,” says Hewitt. “It can be about memory in this other way.” What results are sculptural photographs that challenge our relationship to space, narrative and memory.

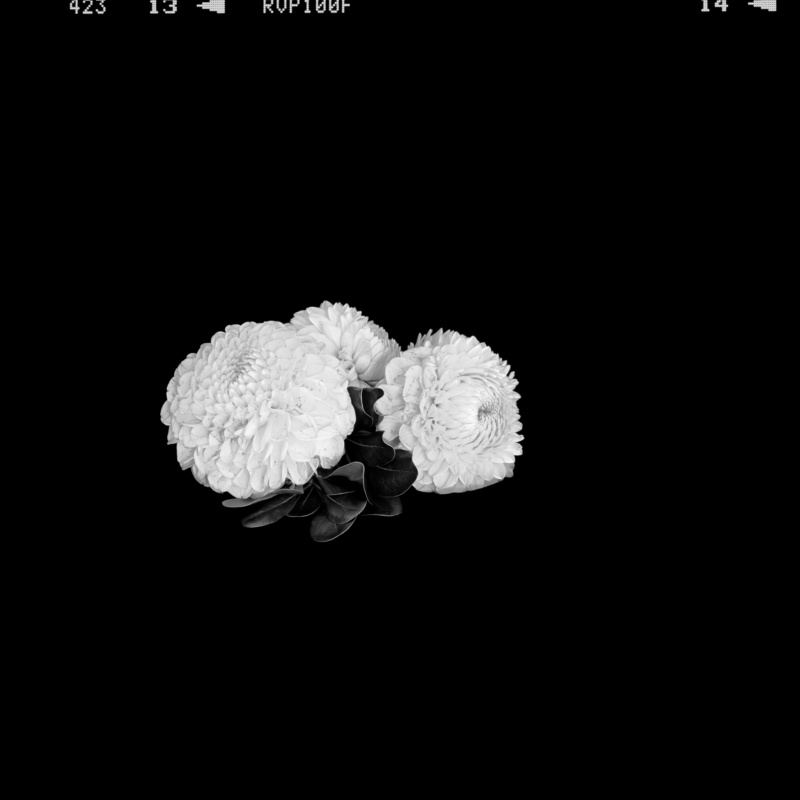

Hewitt’s Aura, 2016

. Digital chromogenic print. Courtesy the artist and Perrotin

Hewitt’s Aura, 2016

. Digital chromogenic print. Courtesy the artist and Perrotin

Hewitt’s still-lifes are often comprised of different types of ephemera—mid-20th-century books written by authors grappling with questions of human rights and race through sociological and poetic means, archival photographs from the ’60s through the ’80s, magazines from the same era, family photographs (though not always of her own family) and handwritten notes and drawings—that encourage new ways of reflecting upon histories. They suggest a shape or relationship, yet never overprescribe their own meaning. Further, as sculptural objects, these photographs become the material through which Hewitt intentionally disrupts the parameters of what the images can do and perhaps more importantly, what they should do. Consider her ongoing series Riffs on Real Time, begun in 2002. Each iteration of the series consists of 10 color photographs that depict a small snapshot laying on top of a larger object placed on a floor of varying surfaces. Scenes of domestic interiors, cityscapes, landscapes, protests and other gatherings deliberately call into question the relationship of time between the images as well as the viewer’s relationship to time and the histories evoked. In this way, Hewitt calls for a new epistemology, a new rendering of how memory is constructed and how its architecture is interpreted.

“I am attracted to being here physically. Sculpture never has to argue that point; it is not an illusion. It is here with you.”

“When I first started to make the prints for Riffs on Real Time, many people asked where the photograph was and I thought that was actually really beautiful. At first it was a critique. ‘I don’t see anything.’ But what an amazing metaphor. ‘I don’t see you; where are you?’ I’m right here, but you don’t see me. How can we both look at something and see different things?” The decision to occupy this “in-between,” is meant to engage viewers in varied modes of seeing and entering her work. “It is not a redacted text,” Hewitt affirms as we walk into her studio space, “it’s here, but it is here in a way that might be less recognizable and requires the patience to make a new relationship, which I think is required of us because of the way in which meaning has been prescribed for us and on us.”

What I know in this moment of exchange is that the “us” is not universal. Hewitt is speaking specifically to and about Blackness. And to disrupt static, linear renderings of black histories is a task that certainly manifests itself through that which is tactile and visual.

Installation View of “Momentum Series 15: Leslie Hewitt”

at Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, 2011.

Installation View of “Momentum Series 15: Leslie Hewitt”

at Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, 2011.

Her series Make it Plain (2006), for example, takes up 1960s Black protest images as its subject. The series features a set of five unglazed color photographs. In the third photograph, a square wooden board rests atop a copy of “Black Protest: History, Documents, Analysis, 1619 to the Present” and the “Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders” by Joanne Grant. A black-and-white snapshot of young Black people sits at the top of this arrangement, resting on its side, and in the upper right corner is a photograph of two smiling Black men. What of quiet resistance? The gathering unto ourselves to rest and take care of one another?

Hewitt’s collaboration with acclaimed cinematographer Bradford Young, Untitled (Structures) (2012), makes use of the Menil Collection’s extensive photography archive to illuminate lesser-known sites that were instrumental to the Great Migration and the Civil Rights Movement. Shot on 35mm before being transferred to HD, the 16-minute-and 47-second dual- channel film take us from the Arkansas Delta to Memphis and then finally to Chicago, traversing, in a nonlinear method, the architecture of an intimate history full of little recognized markers. And yet, Untitled (Structures) does not traffic in nostalgia. Instead, Young and Hewitt use the film as a method for upending a location’s prescribed memory and offer the (moving) image as means of evoking an elasticity in how the history of a place is understood and subsequently inherited.

Hewitt’s work invites us to consider how we know what we know. From where is our knowledge about ourselves and our collective history inherited? What does a collective memory truly look like? It might only be right to argue that such a process is never complete. Instead, we must consistently seek out new, careful entry points into an enduring inquiry.

As I left Hewitt’s studio after our conversation, I was reminded of a few lines from Elizabeth Alexander’s forward to the posthumously published short story collection “Whatever Happened to Interracial Love” by Kathleen Collins. In it, Alexander declares Collins to be a “Black thinking woman,” a woman who “remind[s] us of ourselves,” and affirms that “we were not invented yesterday.” Hewitt is also such a woman.

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.

in your life?

in your life?