This July, artist Njideka Akunyili Crosby and MCA Chicago curator Naomi Beckwith take the stage as part of the Anderson Ranch Summer Series. We asked the pair for a preview exclusively for our readers, and the following interview is a snippet of their conversation, in which the two explore the MacArthur genius grant-winning painter’s singular visual language.

Naomi Beckwith: I’d like to dive right into your work by thinking about the spaces within them. One of the more striking things for me about your work is that many of the objects depict interior scenes, but there’s always a kind of window or space looking out onto a world that is present but still extant to all these scenes. It seems so consistent in works such as I Still Face You and The Beautyful Ones are Not Yet Born; it’s becoming a metaphor for something. Can you talk about the spatial arrangement that happens in this work and where that comes from?

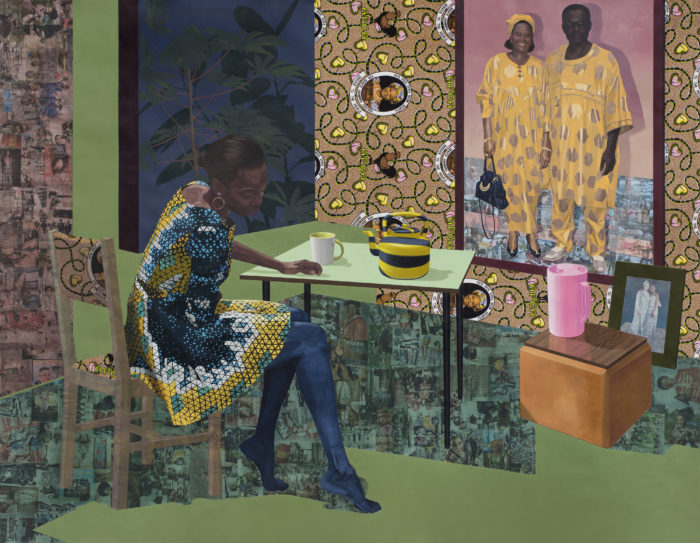

Njideka Akunyili Crosby: This is part of a lexicon I’ve been developing over the years—a window in an interior, a garden seen through a window, certain objects on a table, etc. These objects and plants seen through the window are bearers of heritage and meaning. They in turn tie into a bigger theme I have of differences coexisting next to each other—the part of my work that deals with my immigrant narrative, a narrative which rejects the parts of the American dream that are predicated on assimilation. The assumptions or expectations of assimilation are that you’ll give up your heritage and the cultures you brought with you to become “American.”

This was seen in the recent news from Montana where ICE questioned the citizenship of two American women simply because they were speaking Spanish. The conceit is that you can’t be American if you’re speaking Spanish. That is the path I reject, and so instead I’m making a work that relies on a model of cosmopolitanism that is predicated on maintaining your difference and having that exist alongside other people who are different as well. So with the work, I’m trying to show that my Nigerian-ness and my American-ness exist in the same space.

So inside-outside is one of those things because the outside usually tends to be a mixed space as well—even though some elements show up consistently, like the cassava plant. That’s the plant that looks a little bit like a marijuana leaf but it has a red stem. The cassava plant is something that I associate with rural life in Nigeria. Usually when I’m in Nigeria, I know I’m in the village when I start seeing cassava, so it becomes a stand-in for that. It’s a way to bring that part of my life into this space I’m creating.

NB: You just spoke very eloquently about interior and exterior and difference sitting side by side, and also “Nigerian” and “American.” There are two things I’m really interested in. One: juxtaposition is really important—it’s not just about space, it’s also the elements that really inhabit a space in seamless, but also kind of odd, spatial configurations. Then there is this idea of synthesis, in terms of the Nigerian-American identity amongst women, known as the “Americanah” phenomenon. You seem to be arguing for something a little bit different than synthesis, you’re actually insisting on multiplicity side by side rather than synthesizing itself.

NAC: And only because I believe the two come together to create a new thing, so in some aspects it is a synthesis, but it’s a synthesis that is into something that is unique to your experience.

NB: So that the viewer actually wouldn’t understand that new thing in their own life experience, per se, but they get introduced to it by you.

NAC: I think I’m trying to say that maybe a melting pot isn’t—

NB: No, it’s not the apt metaphor for America. People talk about the salad bowl now, right? It is not meant to be a thing where everything melts into each other. It’s meant to be about the distinctiveness coexisting. NAC: Exactly, as opposed to a bowl of mush.

NB: It just so happens I’ve just returned from a visit to Nigeria. I’m interested in the way that oftentimes, when you’re asked to talk about cultural heritage, you’re asked to speak generally about the country of Nigeria. I know your family is from Enugu, which was the capital of the short- lived state of Biafra. If there’s one thing that Biafra and its existence makes clear, it’s that Nigeria is also a multiplicity of things. I’m just wondering, in your life growing up, what did it mean to be Igbo and what did it mean to be from that region? What specifically is in your work from there, rather than just the general idea of what audiences in the US might expect of Nigeria?

NAC: I’ve never been asked this. Biafra is a very complicated subject in the history of people from Eastern Nigeria and that’s why Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novel, Half of a Yellow Sun, about the Nigerian/Biafran war was so important. The war is rarely discussed, it’s not part of the school curriculum and various parts of the country experienced it differently. I went to high school in Lagos and never heard anyone mention the war. However, in the east where I grew up, there was hardly any family that wasn’t affected by the war. Although people didn’t talk about the specifics of the war, it became a huge marker of time (before the war/after the war) for those who survived. My dad fought for Biafra and never talks about his experience, but will insert “before the war,” “during the war,” “after the war” to stories of his boyhood. The war was very much part of your subconscious if you grew up in the east. Did you make it to the east on your trip?

NB: I didn’t get to go to the east.

NAC: It is very different from Lagos. It’s small, everybody knows each other and everybody’s more alike than they are different.

NB: That’s definitely not Lagos.

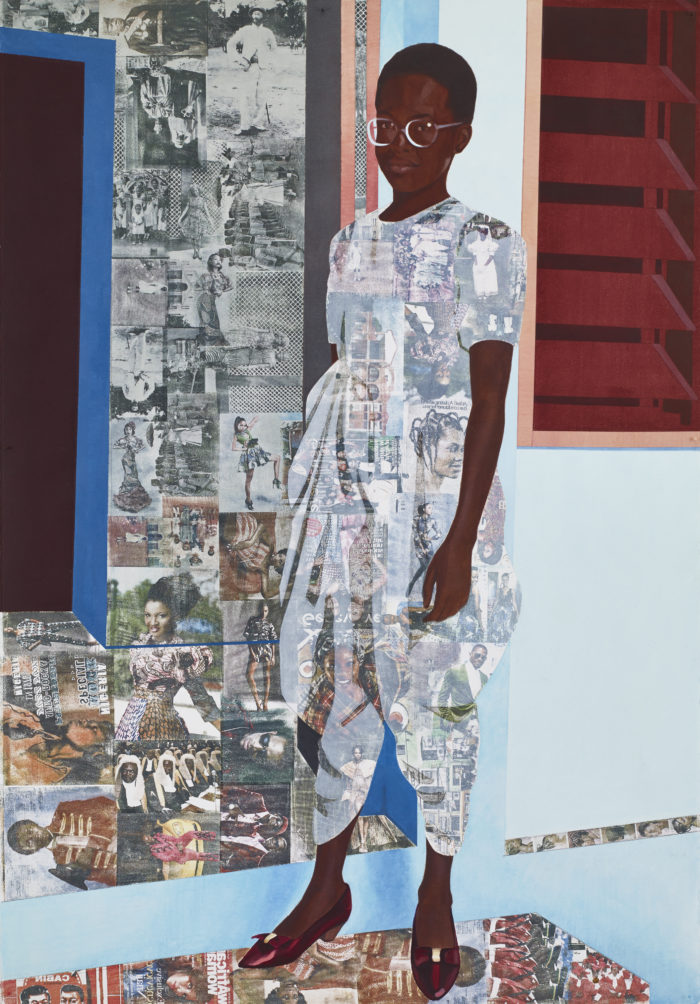

NAC: Yes! For me, the culture shock of moving from Enugu to Lagos was significantly more than the culture shock from Lagos to America. The transfers in my work delve into this move as well as my Igbo/Eastern Nigerian identity. For example, Ojukwu, who was the head of the Biafran Army, shows up in my transfers. For me, another marker of Eastern Nigeria is my grandmother. She spent her whole life in the village. I spent my summers and weekends with her. So I try to allude to that—the threaded hairstyle often seen on the women in my work is associated with village life. I also made the series Predecessors based on objects from my grandmother’s table which I associate with the village, and that is an important part of my life— the most discussed duality in my work is the Nigeria/America split but there’s a whole other part that’s about my relationship to the village/Lagos. That’s why the conversation I have about the work with Nigerians is totally different from the conversations I have about it here. This is the first time I’ve been asked about representation of my Igbo self in the work. That part of my life plays a significant role in my work because I thought of myself as Igbo before I became aware of being Nigerian. When I moved to Lagos at 11, I became aware that I was Igbo. And of course once I moved to the US, I became aware of my Nigerian identity.

NB: You’re exactly right. What you’re saying is that one’s identity really is based on context. What comes to the fore, what becomes most visible is really dependent upon what the backdrop is around you, what comes into the foreground and background. I think that plays out really beautifully in your work too—this idea of foreground and background—what’s considered kind of flat, what’s textured, what’s multilayered, what’s almost monochromatic versus what is really a collage. That, to me, is a really incredible part of your practice. Where did the visual language come from?

NAC: The visual language developed slowly and I’ve been adding to it over the years. Before graduate school, I was making fully rendered charcoal drawings and carefully modeled oil paintings.

NB: And this is at PAFA [Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts] or at Yale?

NAC: This was at PAFA. When I got to Yale, I wanted to start from scratch. I wanted to leave everything I came in with and rebuild my practice.

NB: Why is that? Why did you want to rebuild? NAC: Because I got to a point where I felt I was stuck. I had an idea of what I wanted to do but the work I was making was not it. The conversations I had during studio visits about my desires for my work did not match up with what I was making. Also, it was in grad school that I really started collecting a lot of pictures from Nigeria. Every time I went back home I took pictures. My grad school studio was littered with Nigerian magazines and pictures and during studio visits, we often ended up talking about my image collection instead of the drawings or paintings I had completed. Slowly, I realized the pictures were important to me because they were a way for me to stay connected to Nigeria while living here. They helped me keep pace with the energy and cultural happenings in Lagos; it’s a very fast place!

NB: Oh yeah. It is vibrant, literally at all times.

NAC: Very vibrant and it’s constantly changing— the fashion, the lingo, the music, the cultural scene. I felt like every time I returned I came back to a new city.

NB: And this is annually, basically?

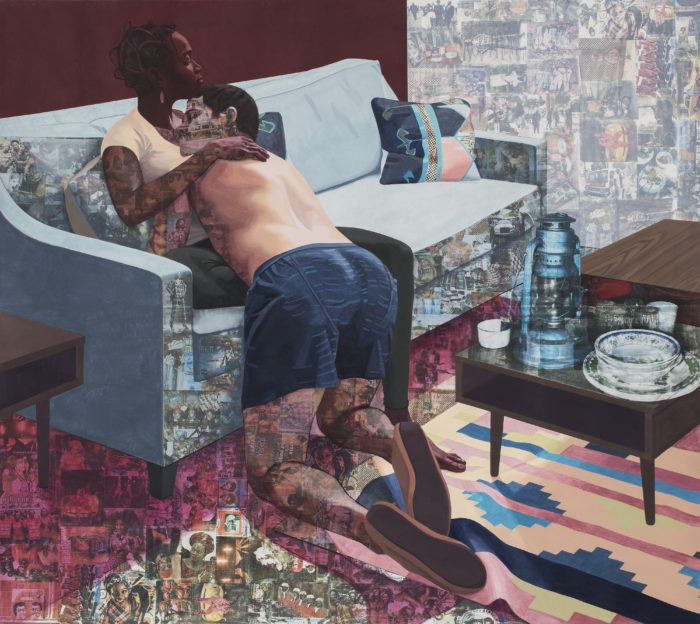

NAC: Yes. I was going back once a year so I used pictures from blogs, Facebook and other social media to keep up. That way when I returned, I wasn’t announcing to everyone that I didn’t belong because I had been overseas. During my time in grad school, I realized that the pictures mattered enough that I should incorporate them into my work. I also liked that they showed Nigeria as a complex and exciting space that people outside the country didn’t see much. I started making collages with the pictures, then the collages got bigger. I missed drawing so I reintroduced it into the large collages. I also started painting some of the flat areas in the work. That’s how it happened. By the time I graduated, all my compositions centered around the characters of the Nigerian girl and her white American partner. I put a lot of thought into the figures but not the background. That I just filled with flat color. My compositions continued thus until halfway through my Studio Museum residency when I decided to stop over relying on the figure. I wanted to orchestrate the background with the same compositional rigor I brought to the figure. For instance, if I was painting my female character, I might give her the threaded hairstyle which speaks to her being a village girl—I still see myself as that.

NB: Aw, that’s sweet. A cosmopolitan village girl.

NAC: Haha. Yes. But then she would have a dress from Tiffany Amber, a hip Lagos designer, and slippers from Hausa traders. So I construct this character to be multifaceted. However, I wasn’t bringing the same attention to the background. I decided to do that.

I decided the best way to force myself to deal with it is to take the figure away and grapple with the space. How can I have just the space say everything I’m interested in? How can a space be a portrait of a place? How can I make a space that speaks to the village and the city, Nigeria and the United States?

Once I felt my interiors were getting complex, I brought the figure back into it and I felt an expansion/growth in my work and lexicon. Then I got to this other place where I felt I needed something else to change in the work. What I realized was I was making these paintings that worked like windows on a wall that you stand back and admire. I wanted to shake that up a little bit and make this thing that wasn’t a window the viewer could just stand from and behold. I wanted it to implicate the viewer more and have them have a slightly topsy-turvy, for lack of a better word, experience in front of it. I started to make the works bigger and multi- paneled, as well as begin to play with perspective and point of view. I’m constantly changing the perspective points and the eye level of the “ideal viewing location” so that the viewer doesn’t quite know where they are. The composition looks fine from afar but once you spend enough time in front of it, those things reveal themselves slowly and you begin to have this feeling of not quite knowing where you are. I’m putting the viewer in this space of difference—by changing the language of image- making within the work but also by manipulating the space so they have this feeling of the ground being slightly uneven under their feet.

NB: I think this is absolutely remarkable. I love the idea that as much as you talk about the juxtaposition and putting difference side by side and your work that happens within the scene, you are also talking about the experience of the viewer also being shifted—I would say unsettled even—which is a great place to be, I think, when looking at work. You talk about the space in your work as almost fictional. You talk about the characters as ‘the girl as based on me.’ And so I want to talk literally about the role of fiction. It feels like your work to me is very much cinematic, very much narrative, very much literary, and can you talk to me about that? What is it to be a kind of visual fiction but somehow still have this real relationship to the world?

NAC: I’m so happy you brought up fiction and storytelling because I count a number of Caribbean and African diaspora fiction writers as major influences. When I was in grad school and struggling to visualize themes that were clear to me, I found kindred spirit in writers from African and Caribbean countries. Most of us were trying to find ways to tell our own very complex narratives (because a number of us have existed in all these in-between spaces) using an inherited tool like language. The salient example being Chinua Achebe, a first generation English- speaking writer who used English—an inherited tradition—to tell stories of Nigeria and his experience as a Nigerian person. I felt like I was doing something similar. I think of myself as a storyteller. In graduate school, the characters in my work were closely based on me and my family members but over the years, they have taken on their own stories and evolved as the narrative I’m building for them has expanded.