For the last few decades, London-based Amanda Levete has been an influential presence in the world of architecture: in the ‘90s and noughties as one half of the groundbreaking practice Future Systems and since 2009 as the head of her own studio, AL_A. With major projects being completed in Bangkok and Lisbon and the recent announcement that the practice has been appointed to transform Paris’s most iconic department store, the Galeries Lafayette, AL_A is about to enter a different league. No project is quite as visible, however, as the new exhibition gallery and all-porcelain courtyard AL_A has designed for London’s world-renowned Victoria and Albert Museum that opens next spring.

“The V&A is a seminal project for us as a practice. I think it’s the one that really marks our coming of age. It speaks a lot about our preoccupations and the values we think are important,” Levete says. She appears calm and thoughtful as she speaks but admits that with hindsight, some of the choices made with regard to the V&A project were “very brave.” One was the decision for the museum to remain open and fully functional while the contractors were “digging a basement 15 meters deep and piling 50 meters down within one meter of a Grade I historic building!”

Another was the practice’s idea to remove parts of a century-old stone wall (or screen) that separated the museum from Exhibition Road and was designed by one of its original architects, Aston Webb. The proposed design leaves just the columns and arches on which aluminum gates will be hung. “Our argument was the screen was designed to hide the boiler rooms, which have long been gone,” says Levete. “Now the purpose is to reveal and not to hide.”

For the first time in its 164-year history, the V&A will open out on to Exhibition Road. At night the aluminum gates will close but the perforated patterns—which are based on the shrapnel damage suffered by the wall in World War II and that, in Levete’s words, “memorialize absence”—allow for transparency whatever time of day.

“It’s not just another iconic building she is creating,” says Martin Roth, the V&A’s director since 2011. “She is doing something really bespoke for the V&A.” The museum has “always worked with contemporary artists and architects,” he continues “and never copied the past.”

Roth lauds Levete’s “attention to detail and understanding of craftsmanship.” Unlike many architects she is not one to be easily deterred by budget or other difficulties. “She is extremely demanding and has very high standards but is someone who guarantees quality all the way to the end,” says Roth.

The ultimate expression of Levete’s commitment to craftsmanship and materials is undoubtedly the all-porcelain courtyard, composed of 14,500 tiles made by hand in Holland’s 450-year-old Royal Tichelaar Makkum factory. A world first, it also demonstrates the practice’s attention to creating inclusive and interesting public space. “I am incredibly interested in designing spaces where people can just be: where they can hang out, take a break and reflect, have events and exchange ideas,” says Levete.

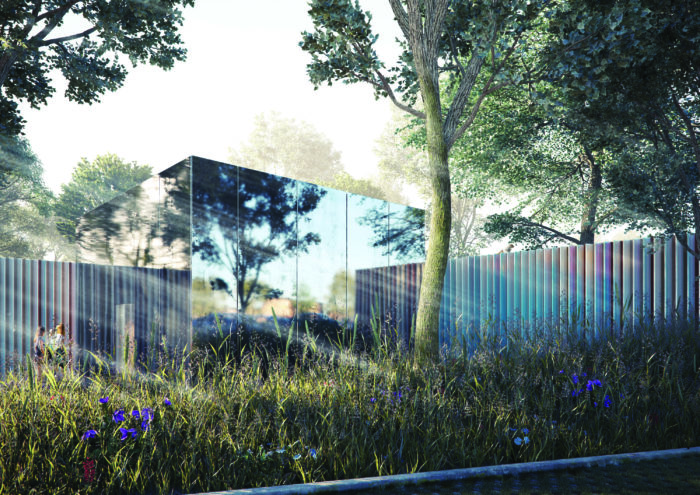

Before the V&A, however, AL_A will cut the metaphorical ribbon in October at the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, a compelling new space located on Lisbon’s riverfront and led by Pedro Gadanho, a former curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. That same month sees the completion of AL_A’s Central Embassy retail and hotel project in Bangkok, its shimmering aluminum skin and sinuous form already an icon on the Thai capital’s skyline.

Its facade was created out of three different tiles and the pattern generated digitally. “We used software to accentuate the line of the tower as it came round and merged into the plinth,” explains Levete. Though software was also used for the color field pattern of the V&A courtyard, Levete is clear that digital technology is about enabling ideas and should never be the idea itself.

“There are a lot of practices for whom software is a driver,” she says. “I am interested in it only insofar as it’s a tool to get to where you want to go. We used it here to heighten people’s perception of certain lines and create a rhythm and a complexity that you wouldn’t be able to do by hand.”

As a practice, AL_A has always been driven by a desire for technical innovation. A few years ago it created a super slim and incredibly resilient table out of ceramics; more recently it experimented with composite materials and technologies used in the aerospace industry to build a slender petal-like canopy for its MPavilion in Melbourne.

“We like to push things as a practice and test the limits of a material,” explains Levete. “But it’s also about how the details are part of the narrative. With the V&A there was a different idea that drove the project, which was this abstract notion of how you make visible the invisible. The big event—the gallery space—is below ground and there’s a certain kind of paradox in that.” A paradox that Levete and her practice has managed to transform into a virtue by giving Londoners a new kind of public piazza—or, as Levete calls it, “an outdoor living room.”