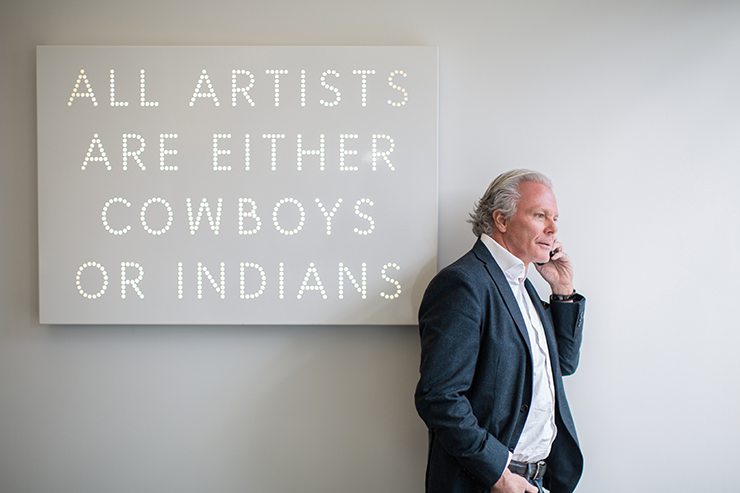

“To a large extent, I don’t want the work to be identifiable as having come from our office,” says architect Roger Ferris. “The idea of trying to create a brand, to me, is anathema to the whole process of architecture. We try to reinvent the wheel every time.” His reinventions are executed for such clients as billionaire Blackstone Group CEO Stephen A. Schwarzman, theater director Robert Wilson and energy trading firm president Frank Gallipoli.

Ferris’ process begins long before the first line is ever drawn, before he places the first door or window. “I think that something is lost when I start to draw too quickly. The line is in one place or the other, and it kind of starts to solidify a notion or a strategy. I’d rather force myself to think about it more fully before committing pencil to paper.”

He prefers to back off and write a story—almost a fiction—about the project, the site, the client. “It doesn’t mean that it makes the drawing easier; in some sense it makes it more difficult because we have more thoughts, more ideas to pursue or more things to explore.” And while Ferris’ firm is tricked out with the latest in technologies (BIM, 3D modeling, orthographic drawing), he admits to not using any of them himself. “Technology is just a tool. I don’t design on a computer. I’m not knocking the firms that get this kind of radical gesture or response where they can get that. But I’m not interested in radical gesturalism.”

Many of Ferris’ award-winning projects are located throughout the Hamptons, among them The Bridge, a golf course in Bridgehampton on the site of what was once a storied racetrack. (Paul Newman was introduced to racing there by Mario Andretti.) “I wanted it to be a place that subverts the norms, the ideas of exclusivity and stuffiness, a place that was welcoming and open.”

The clubhouse sits on the highest point and takes advantage of the expansive views of the water. Ferris’ inspiration was a turbine wheel from a racing engine he found on the site, and translated it into a series of “blades” coming out and framing different views of the landscape. The Bridge has become a cultural nexus for the Hamptons, hosting everyone from the Royal Shakespeare Company to Robert Wilson.

Ferris and Wilson are at work on an underground space for The Watermill Center, which will house Wilson’s collection of works by artist Paul Thek, left to him when Thek died of AIDS-related illness in 1988. The space is something of a cement vault, albeit with 22-foot-high ceilings. It will also serve as a library for Wilson’s enormous collection—more than 40,000 artifacts—of everything from pre-Columbian dolls to bones, which can all be viewed by the public. They are researching the possibility of using an advanced tracking system that would allow objects to be moved by users around the facility, but still always able to be located. So, even though his projects begin with the pen, they often end up relying on progressive technology, as well. “It is, of course, an integral component to realizing the highest level of excellence.”

in your life?

in your life?