Whether he likes it or not, Mark Bradford is one of the art world’s favorite Cinderella stories. All quick wit, good looks and an easy-going charm, the artist—recognized with both a MacArthur “Genius” grant and a National Medal of Arts award—honed his conversation skills wrapping perms at his mother’s hair salon in Los Angeles’ Leimert Park, an experience that would later inform his paintings.

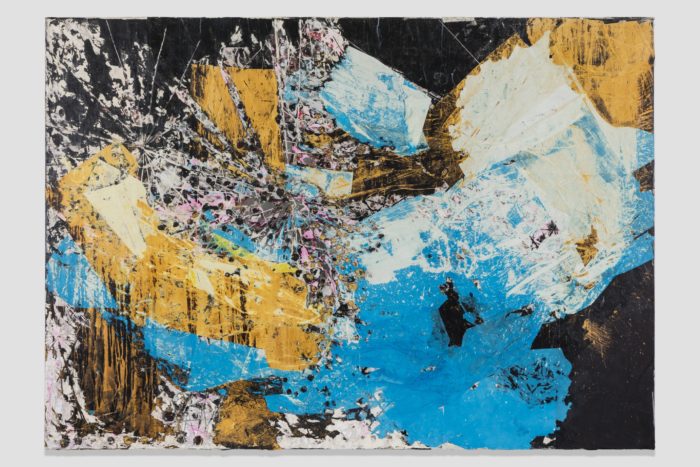

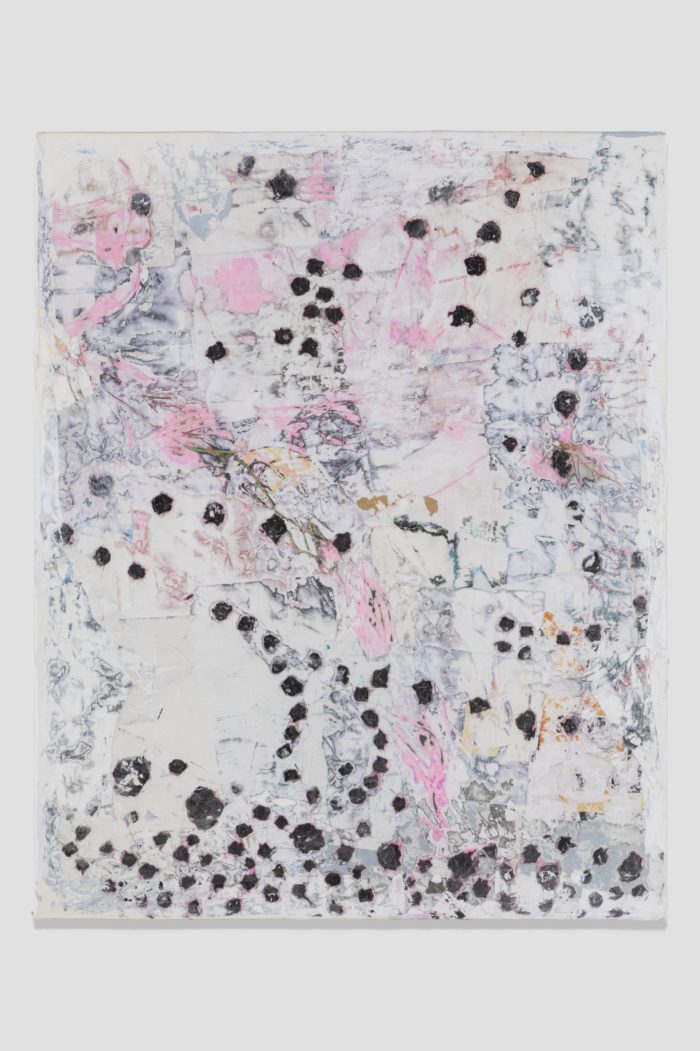

“Paintings” here is applied loosely; Bradford tends to forgo the brush and palette in favor of a good power sander, which he uses to cut through layers of found materials, ranging from the end papers used when perming hair to the homemade flyers advertising payday loans, quickie divorces or—Bradford’s favorite—“Sexy Cash,” frequently plastered around his studio in South L.A. Bradford’s “social abstractions” (as he calls them) can now be found in places as diverse as the Museum of Modern Art and the Los Angeles International Airport’s Bradley Terminal, where this summer he installed Bell Tower, a massive JumboTron-like assemblage hovering ominously over the security checkpoint.

The problem with Cinderella stories is that they don’t leave much space for rage. “There’s a certain narrative I have probably let go on a little too long,” the artist admits when we spoke this summer, a month into “Scorched Earth,” his solo exhibition at the Hammer Museum. “My life was not easy. I always had a smile on my face and I was an optimist, but an ‘optimist’ in the sense that I was thinking, you know, it’s got to get better.” He pauses, adding: “You have to get below the rage, to address exactly the sites that make you feel so disenfranchised.”

As the title implies, “Scorched Earth” took no prisoners as it surveyed the broken foster care system or the willful ignorance around the AIDS epidemic and the 1992 L.A. race riots. “Let’s call them ‘riots,’ not ‘civil unrest’,” he urges. “Don’t cool off things that should be hot.” For the Hammer Lobby, Bradford used his sander to carve out a map of the United States from the hundred-plus layers of paint from previously commissioned wall paintings. Each state is emblazoned with a number, denoting the portion of the population (per 100,000 citizens) diagnosed with AIDS as of 2009, from Vermont’s 1.3, to New York’s 29.2, to D.C.’s staggering 139. Upstairs, a suite of sprawling new compositions based on microscopic close-ups of AIDS cells send rays of red and gold pinwheeling over mottled black-and-white backgrounds.

Just as incendiary as the exhibition is its catalogue, which features authors like Douglas Crimp, Marlon T. Riggs and Hamza Walker tackling taboos around homophobia, racism, the stigmatization of disease and the crisis of black masculinity. All of these issues came to a head in Bradford’s latest media installation, Spiderman, a riff on Eddie Murphy’s 1983 stand-up act, “Delirious,” in which the performer, clad in a red leather jumpsuit, kicks off the set with the statement: “I’m afraid of gay people.” “As an artist, I’m always interested in the moments when something enters into social contract,” Bradford explains. “And for me that was the moment that gay bashing entered into the public arena as something acceptable.”

Bradford recalls standing in the audience with one of his friends. “I remember telling her, ‘careful, you’re next.’ And sure enough only a year or two later, it became okay to refer to women as ‘bitch’ and ‘ho.’” Spiderman channels an entertainer in the vein of Murphy, but Bradford counters the misogynistic posturing of the comedian’s language by making his character a trans-man, a twist revealed towards the end of the piece.

The title for Bradford’s solo show, “Be Strong Boquan,” which is his first exhibition with Hauser & Wirth since leaving his longtime gallery Sikkema Jenkins in 2013—was derived from Spiderman. The media installation is flanked by a series of new paintings, as well as Deimos, a massive video installation that fills one entire wall of the gallery with footage of a roller disco after the party is over. The exhibition opens in the wake of an announcement that Bradford has been commissioned to fill the Hirshhorn Museum with a monumental series of fresco paintings—the largest he has ever made—due to open in November of 2016.

Amidst it all, Bradford has not forgotten his roots. As part of the programming for “Scorched Earth,” the artist participated in a public conversation with Anita Hill, one of his lifelong heroes whom he had met while speaking at the Rose Museum at Brandeis last year. “It was like we have known each other all our lives,” the artist muses. “I mean, in the 1990s, she was disagreeing with another black person in public. That was huge for me. I was so young and scared and beaten-down, but watching her, it was like something was pinging from the outside.”

Bradford now hopes to provide this kind of beacon in South L.A., an area home to a disproportionate percentage of foster youth—with nearly 30,000 of the national total of 400,000. Bradford and his partner, social activist Allan DiCastro, joined forces with philanthropist Eileen Harris Norton (the first person to ever buy one of Bradford’s paintings) to convert several buildings in Leimert Park—Bradford’s mother’s former hair salon among them—into Art + Practice, an initiative that combines cultural programming with job training and support for foster youth aging out of the system.

As Hammer Director Ann Philbin wrote in the prologue to the “Scorched Earth” catalogue, “At a moment when the world at large seems awash in chaos, Mark has done the nearly impossible and made a space for possibility.” Bradford puts it more bluntly: “If you ask to sit at the seat of power, they’ll never let you. You just sit.”