In the fall of 2005, Deitch Projects mounted Kehinde Wiley’s second solo show, “Rumors of War,” an installation of four large-scale paintings inspired by Old Master equestrian portraiture. European dukes and captains were updated with young African American men from Harlem. Imbued with both revisionist and futurist intentions, Wiley depicted Black men preparing for battle and in command. It would foreshadow Wiley’s presidential portrait commission of Barack Obama 13 years later. Nicola Vassell, a director at Deitch Projects, organized the show and, without fanfare, arranged with a donor and Arnold Lehman, then director of the Brooklyn Museum, to place one of the works, Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, in the museum’s permanent collection.

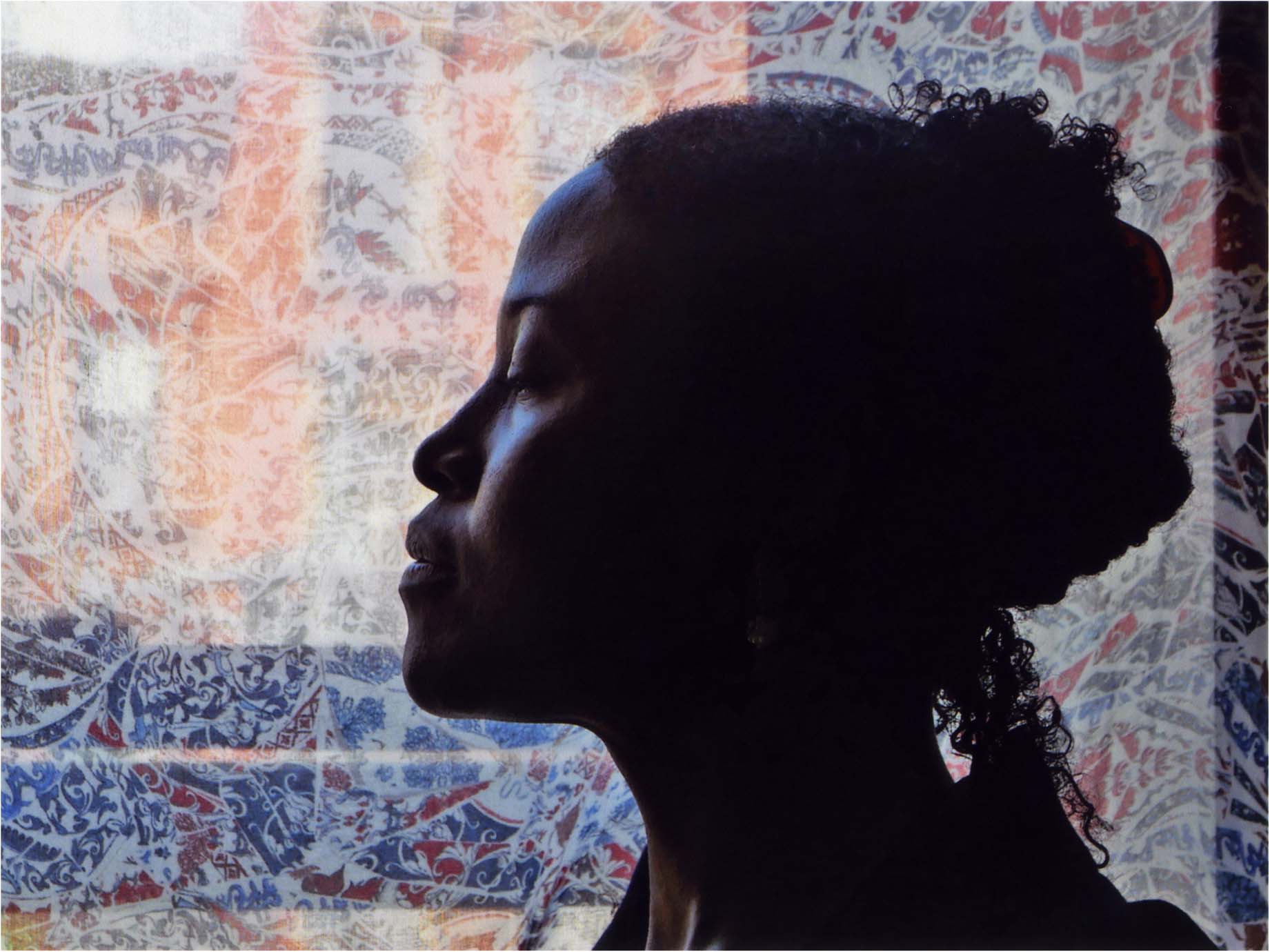

For someone who started her career in front of the camera, Nicola has avoided the limelight while building a career marked by gravitas and future-forward leanings in the ever-morphing contemporary art business. In early 2021, as the “universe finally bends towards some of my ideas,” she will join a small coterie of Black female gallerists when she opens her space in New York City bearing her name: Nicola Vassell Gallery.

At 16, Nicola arrived in New York City and was signed by modeling agency Next Management. The city represented her first taste of freedom, and in quick succession, she landed a Guess campaign, Paris runway shows and spreads in Marie Claire. It was 1997. Black models were scarce, and the Jamaican modeling scene would not take off for another two decades. Some of her earnings went into an NYU education, and she became part of the club scene.

After studying with the likes of art historian Robert Rosenblum, she found a home at Deitch Projects, a gallery-cum-band-of-outsiders art community. Jeffrey Deitch, savvy and pioneering, recognized Nicola’s value from the get-go: a downtown fixture who came with a Rolodex of fashion and press contacts. The fashion industry had given her practical application to the language of aesthetics—texture, color, composition, and light, while waxing poetically on art became second nature. Her forte was managing artists. She knew first-hand what it meant “to be managed” from her stint as a model. There were plenty of positive and negative experiences that shaped her ethos. “I was lucky. I had a few agents who had absolute belief in me, and that translated into my success. They helped me understand how to treat my artists,” she said.

The maxim of ‘work hard, play hard’ undoubtedly characterized her seven years at Deitch Projects. Jeffrey provided her with the fundamental tools of art dealing, and she flourished in the powerful female cartel that included Kathy Grayson and Andrea Cashman. She managed artists Tauba Auerbach, Francesco Clemente, Raqib Shaw, Nari Ward, and Kehinde Wiley. Deitch’s annual Art Parade became a touchstone of what it looked like to be inclusive, ten years before DEI working groups became commonplace. She remains steeped in pride for organizing a number of publications, notably Jean-Michel Basquiat 1981: The Studio of the Street and Francesco Clemente: Works 1971-1979.

When, in 2010, Jeffrey announced that he would be decamping for Los Angeles to become director of MOCA, it was the end of an era but a blessing in disguise. “Art became my life. All parts were so intertwined, every step after Deitch would be an opportunity,” Nicola recalls. A decade later, they remain comrades, and she describes conversing with Jeffrey as always generous and generative.

With a desire to crack the code of a larger art enterprise, Nicola entered the kingdom of Pace, a gallery-behemoth with humble origins: in Boston in 1960, Arne Glimcher, at twenty-two, opened his first space and named it after his father. The current blue-chip stable is a font of knowledge, but it was the writings and teaching of Light and Space artist Robert Irwin that Nicola embraced. “Bob is a hero. His work on phenomenology and perception challenged my eyes to go beyond the frame. He was an outsider and perhaps better for it. He helped me think about looking and being,” she explained.

After Pace, Nicola was keen to tackle a project that was nonlinear and outside bureaucracy. Her determination resulted in a two-year labor of love, an exhibition titled “Black Eye,” which opened in May 2014. As President Obama’s second term represented a reconciliation of fragmented hopes, Nicola questioned the nation’s Black identity and wondered how it might manifest in an art context at that crucial point. The roster of artists (which included up-and-comers Derrick Adams, Sanford Biggers, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Deana Lawson, Simone Leigh, Rashaad Newsome, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Jacolby Satterwhite, Xaviera Simmons, and Hank Willis Thomas) signaled the impending bull market in Black contemporary art.

Shortly after “Black Eye,” Kehinde Wiley introduced Nicola to Kasseem Dean, aka musician and producer Swizz Beatz. Within four short years, their curatorial partnership resulted in a dizzying array of projects. The most spectacular was a series of No Commission art and music events in which pop up ‘art fairs’ broke the traditional mold by presenting artists’ works for sale, where 100% of the proceeds went back to the artists. It was less an affront to the gallery system and more an expansion of how artists can operate. Traversing the globe, No Commission popped up in Miami three times and had outings in Berlin, the Bronx, London, and Shanghai. Each represented a complicated rubric of negotiation, production and presentation. No Commission Shanghai, which focused on the digital future, resonated most for Nicola. “The Chinese youth have so many political and structural obstacles, yet their grasp of technology and connecting it to the human condition struck me,” she noted.

Nicola guided many new purchases for the Dean Collection — which now includes the most extensive body of work by Gordon Parks in private hands. Swizz and Nicola share a professional activist strategy that underlines dismantling racism through story-telling and community support, and they frequently speak about black wealth and ownership. In the fall of 2019, Nicola started to sketch out what a gallery might look like if she were in charge.

By March 2020, her plans were completely upended and stalled by the pandemic. However, as the BLM movement reached a pitch in June 2020, dozens of friends called upon her to hurry up and get it done. A few supporters materialized as private investors ready to stake their money on her fifteen years of expertise and experience.

Defying the current mood, Nicola will double-down on New York by opening a Manhattan space in early 2021. She’s planning to curate nerdy intergenerational exhibitions she has fantasized about for years and will present the photographic work of Ming Smith as her inaugural exhibition.

Nicola surmises, “I want to agitate, create frisson. Black people are not the natural inheritors of certain kinds of spaces. I’m planting a flag and making a declaration.”

All eyes, Black and otherwise, will be on her when she makes her debut this spring.

in your life?

in your life?