In the mid-1960s, John Baldessari changed the course of art history by beginning to incorporate photography onto his canvases. It was a radical shift in form: Baldessari was essentially giving photography the permission to be art where it had been functional before. It’s a different time today, and if Baldessari with photography—or Rauschenberg with found objects or Carolee Schneemann with bodily fluid—taught us anything, it’s that any material should be considered in the creation of an artwork.

Perfume is as much an art, and Anicka Yi has been using it, and its corporeal root, smell, for a number of years. In her biggest exhibition to date at the Guggenheim in 2017, the museum’s gallery was filled with a perfume called Immigrant Caucus, made up of the smell of the pheromones of carpenter ants and the sweat of Asian-American women—synthesized with the help of perfumers.

Yi has now created three separate perfumes—the series is called Biography—available for one week (November 21–28) at Dover Street Market in editions of 1,000. In accordance with the series title, each perfume is meant to tell the story of a person (or sentient being). The perfumes have a vast range, but none would fall out of the realm of being wearable. In fact, they’re all almost a bit too wearable, though as someone who has made perfume for artists, I appreciate that push-and-pull—how much art is too little wear-ability? How little is too much?

For example, the story behind first perfume—Volume 1: Shigenobu Twilight—focuses on Fusako Shigenobu, the leader of the communist organization the Japanese Red Army. The notes are supposed to evoke Shigenobu’s “stateless existence, exiled in Lebanon while yearning for her native Japan,” and make use of aromas associated with Japan like shiso and yuzu, while adding a healthy dose of black pepper, all over a bed of cedarwood.

It’s a bit too nitpicky to say that I don’t necessarily smell the metaphorical stateless existence or the struggle for communism to be taken seriously. How would one express those notes? Do I feel like a Japanese Red Army leader when I shroud myself in Shigenobu Twilight? Or is it simply enough that the perfume—by power of suggestion—makes one yearn for home? And whose home is it that we are yearning for? Is the smell of yearning universal or are we to embody Shigenobu’s state of smelling the smells of Japan and yearn for them ourselves? I’m being a difficult critic, but having smelled hundreds of “perfumes as artwork,” it is hard to dismiss these questions.

As a material art form, perfume is much more difficult to conceptualize than visual forms. It’s not quite abstract—in some ways perfume is like a sculpture or a painting that foregrounds its material qualities. But, of course, our noses—due, it is believed, to the lessening of the evolutionary need for our olfactory system in our survival—are perhaps not as acute as our eyes. Our ability to critique perfume then falls onto the use of metaphor.

I have been in exhibitions where the smell—by design—is jarring. Peter de Cupere, the godfather of olfactory art, recently made a work that mimicked the smell of smog, and it was horrible. I had a sample in my bag after receiving it in London, and I would whiff it as it snuck out from my bag during my travels and I would cringe. But it smelled very much like smog; I would never wear it, but I would call it successful in its intention.

The smell of Yi’s Immigrant Caucus has been described as fairly unpleasant, and deliberately so. Is the Biography series less of an artwork, because it appeals to a broader audience? These perfumes are based on strong women, both real and imagined, and perhaps that is where their success lies, in more abstract sensuality. However, allowing such concrete concepts to be carried by abstract smells is becoming more and more common in independent perfumery. So what stands on its own? The concept or the perfume itself?

Volume 2 is inspired by Hatshepsut, the successful and powerful pharaoh; a female pharaoh was a rarity when she began her rule in 1478 B.C. The final volume was made in the mien of a hypothetical A.I. woman. Both of these—if you close your eyes and suspend your disbelief—may allow you to agree that they are Egyptian-powerful and futuristic-feminine respectively. But more than that, they are nice to wear. I wore each of them around for a day and found them to be pleasant. Like a fine fragrance.

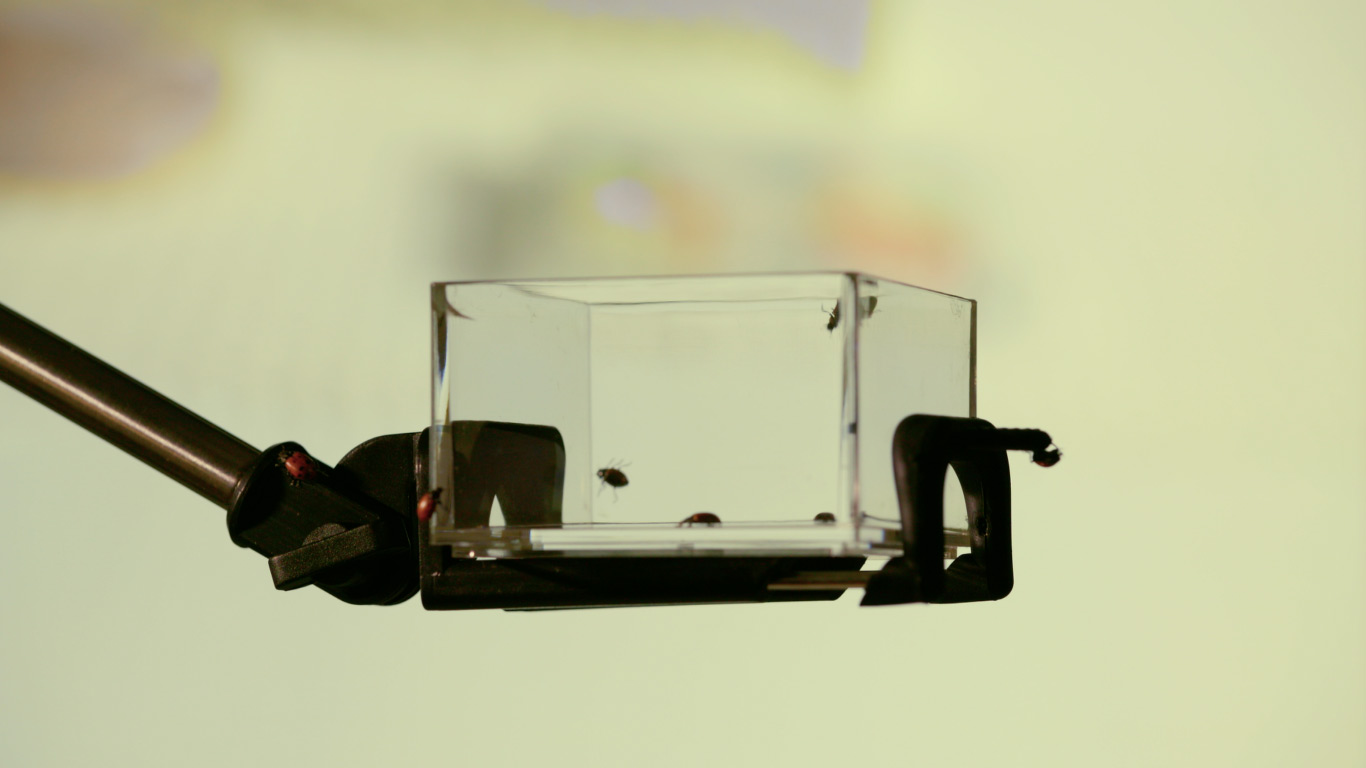

For each of these perfumes, Yi worked with Barnabé Fillion, the young France and Mexico-based nose behind Aesop’s Marrakech, Le Labo’s Geranium 30 and Paul Smith’s Portrait for Men and Portrait for Women. The bottles are as much of a part of the Biography series: made of ladybugs, flies and ants encased in Lucite, they stop time and look beautiful on a shelf. Again, like a fine fragrance.

in your life?

in your life?