Two rectangles sit side-by-side, one black with white text, one white with black text, like a modernist yin-yang or a photo and its negative. “WilliWear”—the clothing brand, launched in 1976—is written on the left in a white sans-serif. “Willi Smith”—the designer, born in 1948—is written in black on the right. The logo, designed by Bill Bonnell, appears on print ads and as garment tags, a motif of contrasting and inversing tones that repeats throughout the designer’s ample body of work.

It’s what New York-raised architect and designer Rafael de Cárdenas remembers about WilliWear by Willi Smith. As a high-schooler, living in Manhattan’s Upper West Side in the mid-’80s, “where all the WASP-y moms wore Laura Ashley and white headbands,” de Cárdenas recalls copying this WilliWear advertisement into his yearbook page: “It was of a light-skinned black woman wearing contrasting polka dots: the bottom was black on white, the top white on black. Willi Smith represented nightlife in the daytime to me,” de Cárdenas explains. “He symbolized a culture I wanted to participate in but didn’t yet have the words for: progressive downtown gay culture.”

We’re on the phone, and I realize our current locations mirror-flip his memory: de Cárdenas is in his SoHo studio-office, not far from Smith’s old Lispenard Street loft, while I’m at home Uptown. I also share underage memories of WilliWear. Though I was raised in Eastern Canada and am a decade younger than de Cárdenas, my parents had shopped in Los Angeles and San Francisco in the 1980s. Among their garments that I absconded with once I was old enough to appreciate their value were Jean Paul Gaultier knits, Girbaud jeans, a Public Enemy concert tee, petites by Issey Miyake and big, soft cotton shirts tagged WilliWear by Willi Smith.

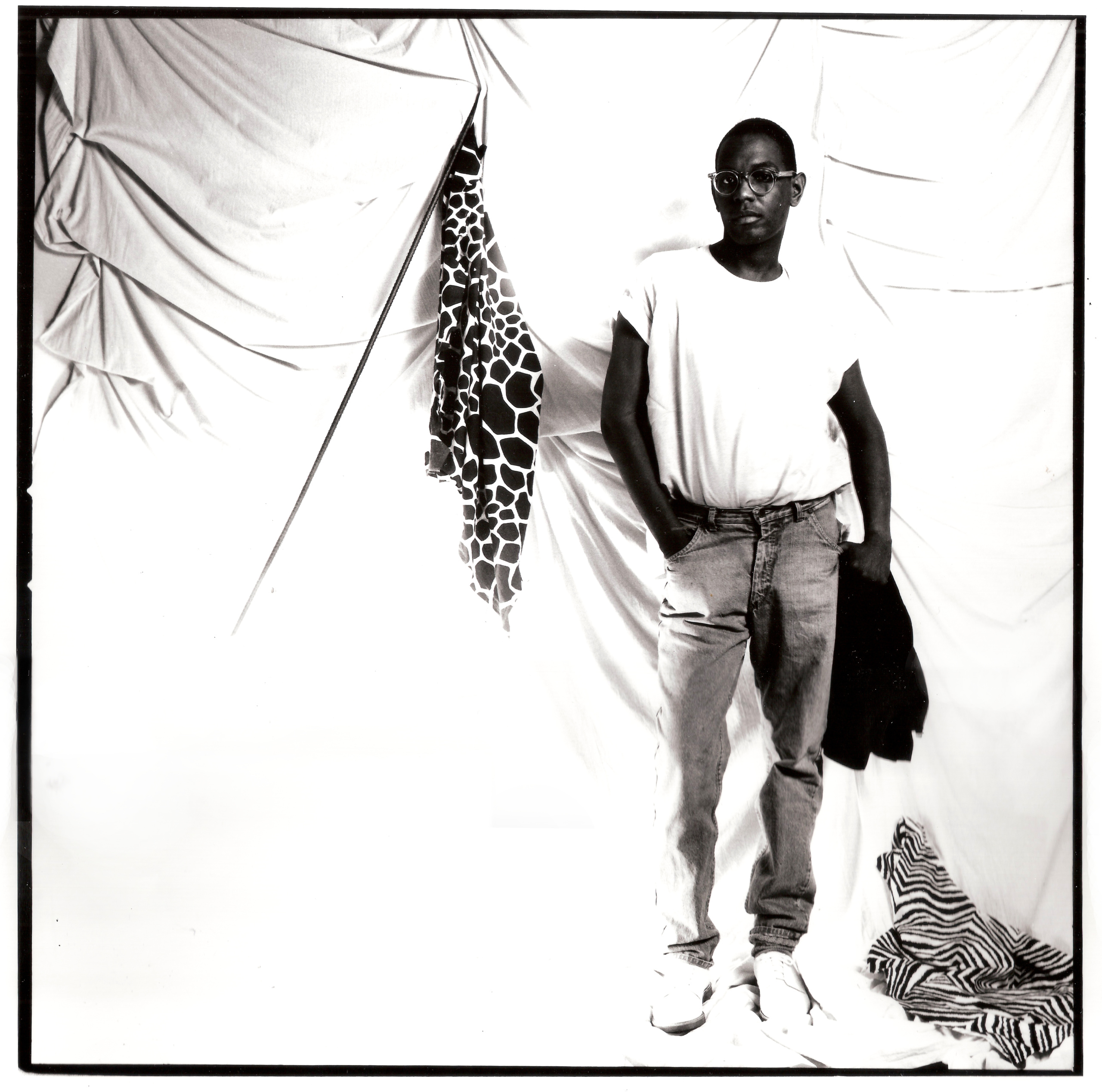

As a child, I confused Willi Smith with Will Smith since the latter was more famous; he was on TV all the time. Both Willi and Will Smith were “in West Philadelphia, born and raised,” like the Fresh Prince of Bel-Air sings in the show’s opening sequence. Old enough to be Will’s father, Willi had no kids. He did have a younger sister, Toukie, a fashion model who will segue into acting, open a West Village restaurant and have two children with Robert De Niro. Before that, she played muse to Jean-Paul Goude, Guy Bourdin, Issey Miyake and her brother—an openly gay fashion designer and a hardworking success story whose clothes appealed to socialist artists like my parents and fashion-conscious society ladies like de Cárdenas’s mother alike. And that was Smith’s goal. As Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, curator of a forthcoming exhibition on WilliWear and Willi Smith at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, tells us: “Smith didn’t consider the work he was doing a success unless he saw people on the street wearing it. ‘I want people,’ he would say, ‘diverse people, all kinds of people, to see themselves in and to use my clothing to express themselves.’”

The Cooper Hewitt show and its accompanying Rizzoli monograph are figuring WilliWear as “the bridge from sportswear to streetwear.” Sportswear, a tradition Smith was trained in, is an American fashion category for adaptable separates, though not necessarily specifically athletic garments. Streetwear, which took root in the nineties in the US and in Japan, is arguably the most globally influential style of dress today. Though countless designers from Yves Saint Laurent to Vivienne Westwood had taken “inspiration” from sub- and street “cultures” before him, Smith was perhaps the first designer in an elite position to insist that his garments were both generated by and for a democratic populace. “I don’t design clothes for the Queen,” he famously said, “but for the people who wave at her as she goes by.”

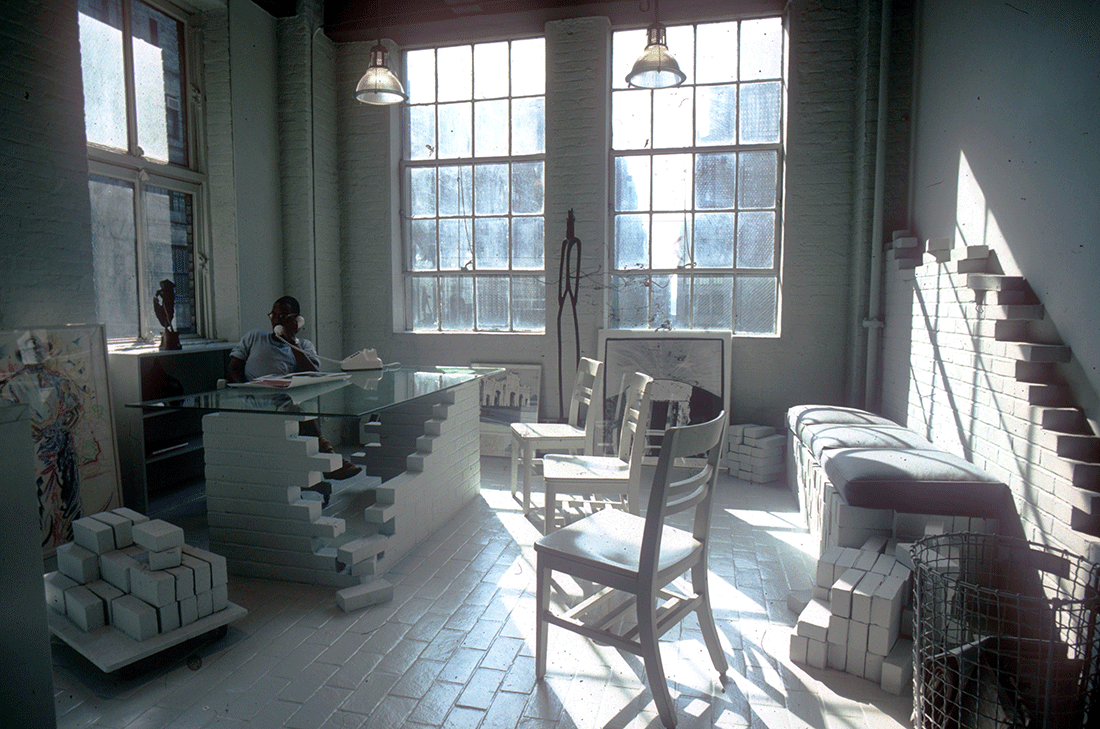

WilliWear was priced to sell widely; not cheap, but fair, especially given its quality. The brand employed terms like “urban optics” (to describe a series of black and white prints), “SUB-Urban” (the title of a 1984 collection) and (for a 1983 collection) “Street Couture,” a phrase used repeatedly thereafter by press and marketers to describe Willi’s wares and now serving as the title of this year’s Cooper Hewitt exhibition and Rizzoli book. Further consecrating his commitment to the street, Smith’s midtown showroom, one of the first examples of “experiential retail,” designed by James Wines and Alison Sky of SITE (Sculpture in the Environment), had, as The New York Times described it in 1982, “concrete floors, furniture that appears to be an ad hoc arrangement of loose bricks and building blocks, police barricade space dividers and backgrounds that are collages of urban textures—sidewalks, doorways, security gates, steel deck plates, sewer vents, standpipes—all arranged into a streetscape and painted putty gray.” Researching this iconic space, which will be recreated by SITE as part of the exhibition, Cameron learned from Wines “that the place he, Alison and Willi went to pull this specific aesthetic was the Christopher Street Piers, an iconic site of gay cruising culture in ’70s and ’80s New York City,” famously immortalized in photographs by Bronx-native Alvin Baltrop, journals and art by David Wojnarowicz and the slice of light installations of Gordon Matta-Clark. A selection of original photography from Sky, Wines and Smith’s walks through the piers will be on display. In my favorite of the photos, a ladder, unstraightened from use and several feet off the ground, edges up aluminum siding; framed by concrete and red brick, the composition is like a flag of New York City textures. This image is one of many pieces positioning Smith within LGBTQ history. “This is an aspect of the show that’s so strong,” Cameron notes: “Willi Smith as a role model for the queer community.”

In Smith’s April 20, 1987 Los Angeles Times obituary, which claimed the designer died of pneumonia complicated by shigella—a parasite he had picked up during a fabric-buying trip to India rather than from AIDS-related complications, as would later become known—Smith is tributed as “the first designer to create clothes for men and women within the same organization.” Reviews of Smith’s runway presentations often commented on how his designs were, as The New York Times fashion critic Bernadine Morris put it in 1986, “so clean and basic they could be worn by both men and women without causing any raised eyebrows.” WilliWear was unisex before the trend; decades later, this exceptional ethos would become a norm for 21st-century queer American brands such as Hood by Air, Telfar, Eckhaus Latta and 69.

Both the spirit and look of WilliWear by Willi Smith permeate contemporary fashion, art and design. Smith’s messages of inclusivity are precisely echoed by the hyper-influential Liberian-New Yorker Telfar Clemens, whose self-described “horizontal, democratic, universal” label is “for everyone.” WilliWear was normcore before the meme, privileging comfort, accessibility and simplicity. The designer made uniforms for the workers who executed Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s 1985 wrapping of the Pont Neuf bridge in Paris, precursing Virgil Abloh outfitting security guards in Off-White Nikes for his solo show at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago last year as well as Telfar’s 2017 uniforms for White Castle servers and forthcoming collaboration with Gap.

Smith also created costumes for the movies (Spike Lee’s 1988 School Daze); for comic books (he designed Mary Jane’s wedding dress for The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #21 [1987], even cameoing as an illustration in the issue); and for performance art (working with choreographers Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane, composer Peter Gordon and Keith Haring on set design for the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s 1984 production Secret Pastures). Cross-disciplinary collaborations such as these are now commonplace, as are fashion films, which Smith was early to engage in. Expedition, shot in Senegal in 1985 for WilliWear’s Spring 1986 collection, plays with themes of colonialism and racial stereotypes in a mythic “Afrique.” The palette of the garments and the film—sun-bleached pinks, reds, blue and tan, colonial white, golden yellow and stalk green on sand, grass and sea—along with the American-African homecoming storyline in which Smith plays six parts, from a ship’s captain to a local woman—recalls popular music videos of the last decade: Solange’s “Losing You” (2012), filmed in Cape Town, South Africa and Blood Orange’s “Chamakay” (2013), set in Georgetown, Guyana, where the musician’s mother is from.

Of course, pop culture repeats itself. Especially fashion. Fashion culture functions like an ecological system, replete with perennial manifestations that seem to disappear (go underground) only to flower and fruit again. But fashion’s fickle flickering does not excuse the whitewashing of history. As critic and professor Eric Darnell Pritchard writes in his essay “Vernaculars of Black and Queer Remembering” commissioned for the Willi Smith: Street Couture monograph: “…many Black LGBTQ people have found that Black LGBTQ ancestors and elders have been excluded from historical records. A troubling impact of the ubiquitous practice of ‘historical erasure’ is that many Black LGBTQ people struggle to achieve the identity affirmation, sense of historical achievement, and communal connection that others enjoy from having ready access to histories that document, preserve, and celebrate their group’s life, culture, and politics.”

“Most people don’t know who Willi Smith is,” de Cárdenas bluntly stated. “It’s bold of Cooper Hewitt to do this show.” Popular history, maintained by power elites, has always excluded stories from the margins. Now, industry holds power. Visual artists stand the greatest chance of being memorialized because the art market can profit wildly off their work, post-mortem. Authors may be worth eternalizing too, if their books continue to sell in print. An architect’s legacy can house many lives. But unless a fashion designer is turned into a house—which was tried with WilliWear (Andre Walker briefly led the design after Smith passed and there was a mid-nineties label reboot through T.J. Maxx)—they risk disappearing from popular consciousness. At the time of writing this, the most extensive online documentation of WilliWear by Willi Smith is a 15-minute YouTube fan video compiled from old VHS recordings and magazine scans: uploaded eight years ago, it has four-thousand views.

Fran Lebowitz and Sarah Schulman have written and spoken extensively about the impact of the AIDS crisis on New York and on global culture. “A whole generation of gay men died practically all at once,” Lebowitz told Interview Magazine. “The first people who died of AIDS were artists. They were also the most interesting people. The knowing audience also died… [AIDS] decimated not just artists but knowledge. Knowledge of a culture.” This is the premise of Schulman’s exceptional historical memoir The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination. Like Schulman’s book, much of the WilliWear exhibition and monograph have been generated beautifully, but also by necessity, from the testimonies of folks who knew and knew of Willi Smith and his work. Dozens of voices—from choreographers Dianne McIntyre and Bill T. Jones to artists Brendan Fernandes and Nam June Paik, poet Tom Healy, editor Kim Hastreiter, fashion designer Jeffrey Banks and Smith’s business partner Laurie Mallet—have come together to restore history. Recognizing there are still gaps in the story, Cooper Hewitt has created a digital community archive where folks are invited to upload personal photographs, ephemera, garments and anecdotes related to the life and work of Willi Smith. “What I remember most,” film director and former head of communications for WilliWear Mark Bozek writes, “beyond [Smith’s] creative genius, are his endless fits of laughter at the spectacle of life.”

in your life?

in your life?