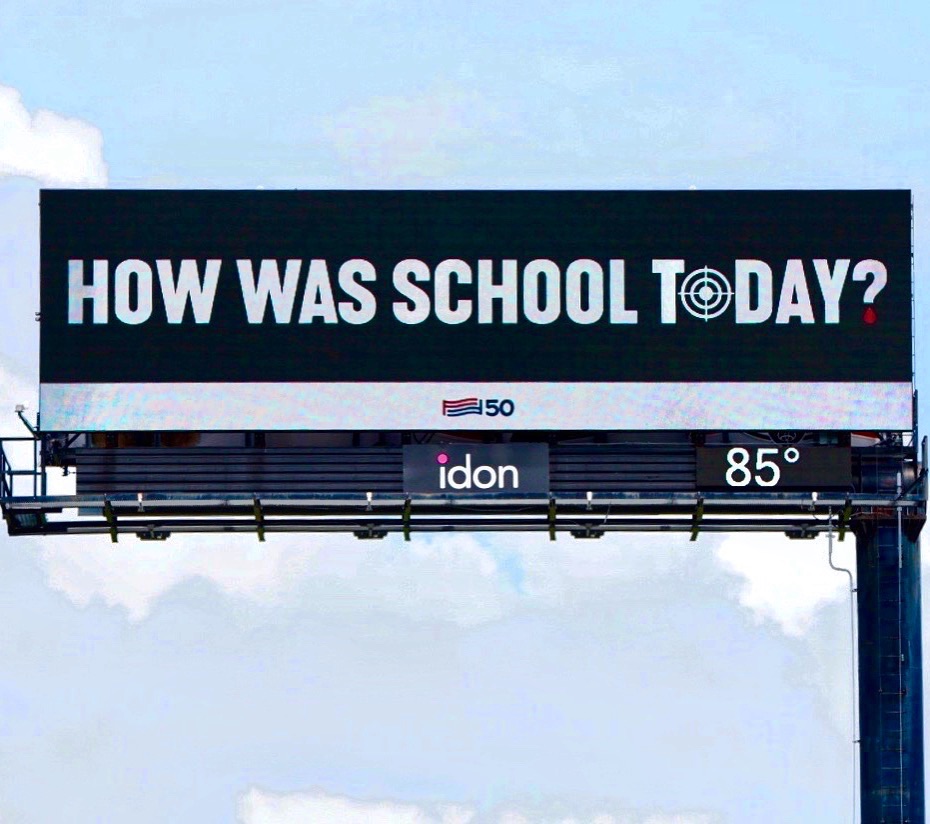

Artists Stuart Sheldon and Zoë Buckman both created billboards for last year’s For Freedoms 50 State Initiative. As the largest creative collaboration in US history, this endeavor engaged over 300 artists nationwide, reflecting a multiplicity of voices that sparked national dialogue about art, education, commerce and politics. For his billboard, “How Was School Today?” Sheldon was awarded an Ellie Creator Award from Oolite Arts, celebrating “the individual artists who are the backbone of Miami’s visual arts community.” When the Perez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) invited Sheldon to share what he learned and lead a town hall discussion on “How Success is Measured in Activist Art,” he invited Buckman to join him in exploring their practices and evolution in the so-called activist artist space. Join them Thursday, November 7 at PAMM, along with some of America’s frontline creative activists and thought leaders, as they examine activist practices and personal benchmarks for success. Before that, read them interviewing each other; beginning with Stuart’s questions for Zoë:

Success in art is a tricky idea. Most measure it through sales. But we’ve both been around long enough to know that is but one piece of a multi-dimensional equation. How do you measure success as an artist? As an activist? What do you consider your successes?

It’s tough because, honestly, I feel uncomfortable with the label activist. I don’t feel I’ve done enough, or am doing enough. I think that Imposter Syndrome is synonymous to the female experience, and it’s certainly a British trait too! It’s taken some time for me to be comfortable owning that I’m an artist, and seemingly even longer for me to be okay with my activism, and okay with where I fall short with it.

I will say this though: it’s become increasingly evident to me that my work moves a lot of people, and makes a lot of those who identify as female feel seen, or heard. My recent show seems to have hit on experiences that a lot of women find difficult to speak about, and so they’re coming to me and sharing their experiences and responses, and for that I am so humbled, and so grateful.

Thanks for the private tour of your recent show, “Heavy Rag,” at Fort Gansevoort in New York. Your superpower seems to be finding the razor’s edge between delicate and fierce, beauty and agony. The result is magnificent tension. Similarly, when your mother died recently, you shared your devastation in real time on social media. Every word you wrote celebrated the singular woman she was, her profound influence on the woman you are and your immeasurable heartbreak at losing her. All of it exposed universal truths which, for me, is the ultimate aim of art. Few can go there in a public forum, but you did it with absolute power and total vulnerability. Tell me more about this gift you have of blending pain and beauty? Is it a survival mechanism? How did it evolve?

Making work out of one’s pain is something I learned from my mother. She was a playwright and her work was often autobiographical. I think I use beauty (its tactile and aesthetic qualities) in my work to try and start nuanced conversations and express complex ideas. What I mean is… violence is ugly. It’s also unfortunately an intrinsic part of the female experience. But so is pleasure, spirituality, the ability to nurture, to choose softness. So why make ugly work about violence? I’m more interested in painting a broader picture that includes all the shades and layers.

You once said that the birth of your daughter, Cleo, in 2011 “sparked your career.” What did you mean by that? My entire emotional paradigm shifted when my children arrived. What changed for you, your practice and your approach to creativity?

Becoming a mother was a hugely empowering landmark for me, and I think it had a lot to do with my being quite young and not particularly comfortable in my skin. I had never called the shots for anything before, and suddenly I found myself giving birth at home with no pain meds and feeling completely in control, and in step with my instincts. I just knew what to do, and how to command the space and bring the baby in and I felt bad ass. After that something shifted: I felt powerful for the first time ever, and at the same time utterly vulnerable and completely open. I felt like my vulnerability was my power, in a way. And so I shed a lot of my attachments and insecurities and decided to just create from an instinctual place.

We coincidentally collaborated on a 100-foot For Freedoms mural in Miami in 2016 back when the organization was just starting. Is your work more solitary or do you seek out collaboration?

It’s so solitary! And I think that right now it needs to be more solitary than collaborative. I think I’ve spent a lot of my life being overshadowed by big personalities. I’m drawn to them. I seek them out because it’s familial, and because I likely have issues standing in my own light, but as I’ve gotten older I’ve realized that I need to adjust that, and so my art practice has been a space for me to wild out and be me, and not be trodden on. I guess I’m a bit attached to that now. I have to keep myself in check and make sure I remain open and generous too though. There’s a balance between not giving your power to others but rather sharing your power.

What do you want?

Personally, and selfishly, I want to give myself time to recover. The past three years have been insane, man! I got divorced, moved home, transitioned my daughter through the pain of those changes, fell in love again with a man who threatened my emotional, sexual and physical safety, was unable to stop my mum/best friend/guide from slipping away. Got my heart broken while grieving. I mean… it’s been REAL. I want to be okay with being by myself for this next chapter, and that’s gonna be my number one job. Second to that will be being a mom and to keep striving for authentic ways to tell mine and others’ stories through my work.

And now, Zoë’s questions for Stuart:

Your billboard “How Was School Today?” stopped me cold, and yet you are one of the warmest people I’ve met in our industry. What is the relationship between the light and dark within you, and within your art practice? Have you developed tools to stop the two becoming muddied?

My fine art practice began in the midst of intense darkness, as I tried to heal my broken heart after a devastating divorce. Though I didn’t realize it at the time, I made “activist art” from day one, because my paintings were super intentional, aimed at specific outcomes. When I finally stopped feeling sorry for myself, I did three things that changed my life. First, I clarified exactly what I wanted most—a loving life partner. Next, I made a plan—I created the silhouette of that woman I desired. Last, I executed that plan by painting that image constantly over two years. I still don’t fully understand it, but just after completing the last of these thirty-plus paintings, I met someone charming and funny and gorgeous. In fact she is now my wife and the mother of my children. Crazy thing is … she looks exactly like the figures in the paintings; it’s like an outline of her body. Ironically, though coming from a sad and desperate place, those early paintings were bright and upbeat, as most of my work has been for the past 20 years. So, for me, when that darkness collides with the lightness of optimism and action, magic happens. It’s just in these past few years that the work itself turned really dark and foreboding, like my For Freedoms billboard.

How do you measure the success of an artwork? Or of your activism?

My artwork succeeds first when I enjoy and grow in the process of making it; double bonus if I get to spend time in that ecstatic flow state! Because so much of my work has a specific intention, it succeeds again if my intention is actually realized, like meeting my wife; or after we got married and had a lot of trouble having kids, I went back to the studio and made a series expressly to bring forth a child. And he arrived later that year. The work succeeds a third time when another person grows from it, no matter how that might be defined. Like you, I never considered myself an activist, per se, but I’ve always had a keen sense of fairness. I think the antidote to unfairness is human connection, because, if we feel connected to others, we’re less likely to tolerate unfairness toward them. So, as a writer and an artist, I’m hoping my creativity somehow translates my struggles and my joy into a universality that helps people understand their own journey more clearly. Success can be as simple as making someone smile. But, in today’s hectic environment, I’m hoping to actually change people’s decision-making and behavior. I don’t consider this political. It’s cellular. It’s helping find our shared humanity.

You mentioned that when you became a father your emotional paradigm shifted, did that effect your choices as an artist? How so?

We were living on a houseboat in Sausalito when my first child arrived. My wife and I had struggled so much and really thought we were not going to be able to have kids, the one thing we wanted most of all. When our son arrived, healthy and perfect, two amazing things things happened: my gratitude level skyrocketed and has never come down to this moment; and my considerable ego evaporated like mist in the California sunshine. The realness, permanence and sheer delight of fatherhood filled the silly spaces where my quest for artistic recognition has been. Now, my practice is about the making itself. I don’t need to be famous, just happy.

What’s next for you? And what do you want?

I’m excited for our gig at PAMM together. My practice is in a state of flux now that I’m living in a remote corner of the jungle by the sea. Spending significant time with my children and my wife in nature, surfing every day, free of so much toxic noise, I’m realizing how much I value tranquility, something the city boy in me never fully realized. After years responding to pain as an artist, I’m experiencing a much stronger emphasis on joy in my new work, because that is what I most wish to activate.

in your life?

in your life?