Firelei Báez was born in the Dominican Republic on the island of Hispaniola, where Columbus first arrived in 1492. “It was the oldest colony in the new world,” says the thirty-nine-year-old artist of her homeland, for centuries a pivotal crossroads that relied on slave labor from both Indigenous people and Africans transported across the Atlantic on the Middle Passage. “Economies were tested, populations mixed,” says Báez, who moved to Miami at age eight with her mother and sisters and has been based in New York since coming to Cooper Union for art school. Though now viewed largely in terms of its tourist culture, the Dominican Republic, she poses, “was like the Petri dish for modernity.”

In her expansive studio in the Bronx, Báez is turning her imaginative lens on the place of her early upbringing, plumbing its diasporic histories and mythologies in a series of massive canvases measuring more than eight-by-ten feet. Fantastical female characters and botanical or watery landscapes are painted over blown-up reproductions of historical maps representing fluctuating views of the Caribbean within the larger world. Eight of these were on view this spring with James Cohan in Tribeca, in Báez’s second show with the gallery.

In one painting, a stunning, braided serpentine creature winds across a 19th-century map reflecting economic investments in the Caribbean. Báez says the figure was inspired by the Native American Taíno queen, Anacaona, who chose death over becoming the mistress of one of Columbus’s captains. “She’s a revolutionary icon that Dominicans and Haitians, who can’t agree on anything, agree on,” says Báez, whose father is of Haitian descent and mother is Dominican, and who lived along the border of the two countries as a child. “I was thinking of her as this avatar of female resistance, from the very first step of colonization to the present.”

Other paintings include versions of the Ciguapa, a wild female trickster of Dominican folklore. Báez began incorporating this figure into her early abstract work during a pivotal residency at Skowhegan in Maine, before getting her MFA at Hunter College in 2010. “She was always sold to me as a warning of what not to be,” says Báez, who describes herself as a child “hellion” and always admired Ciguapa’s freedom. “The only fixed things about her are that she has a lustrous mane of hair and her feet are backwards so she’s traceless.”

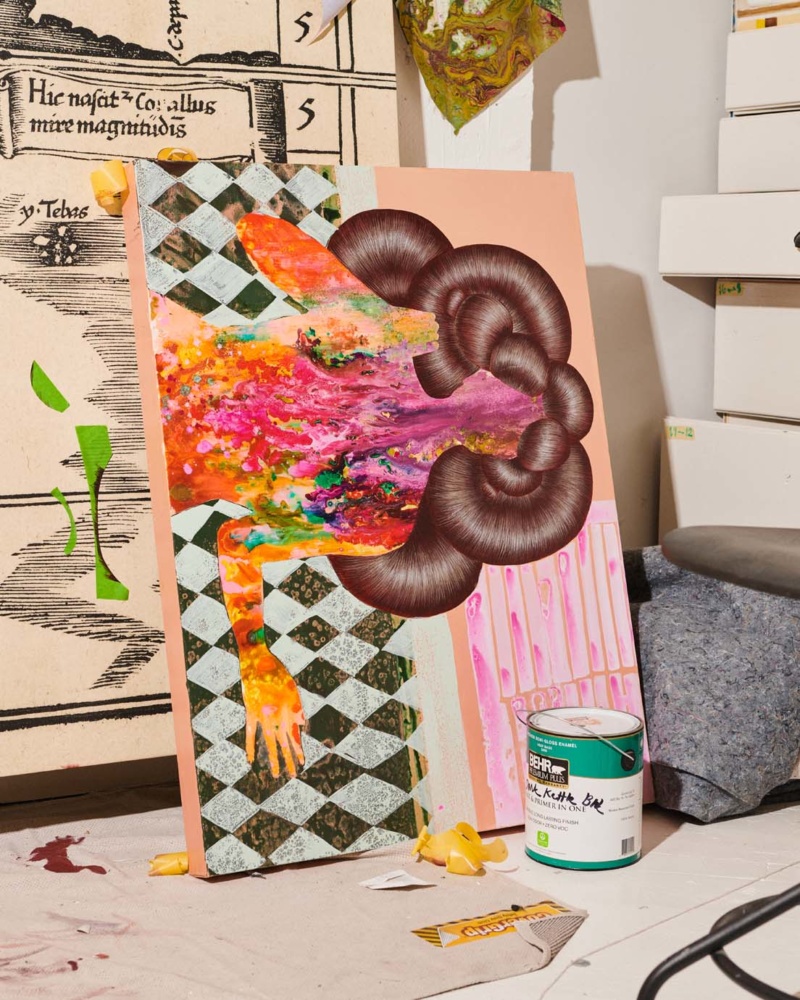

On a 1645 map positioning the countries of the world in a spiral, with France at the center, Báez overlays a Ciguapa with coils of hair and lush flora mushrooming from two tapered legs. “These hair balls almost become like spider eyes, so the thing you think isn’t looking at you is constantly looking back,” says Báez, one of six artists shortlisted for Artes Mundi 9 who will show work at the National Museum Cardiff in Wales next fall. The furry legs of another Ciguapa stir the waters of a kiddie pool, whirling over an 1846 map of the ancient world from the end of the third Punic War in 146 B.C. “It’s taking epic history with a grain of salt,” says Báez, who likes to reenvision past, present and future possibilities through her layered, hybrid imagery.

Báez will similarly collapse time and geography, but using different media, in her largest sculptural installation to date originally set to open in late May at the ICA Watershed in Boston. There, inside the former warehouse in a working shipyard, she is reproducing a section of the architectural ruins of Sans-Souci Palace. The palace was built in Haiti shortly after a successful revolution led by enslaved people overthrew the French colonial government at the start of the 19th century, but was then devastated by an earthquake in 1842.

“It’s as if the waters have receded and up comes this ruin from the Boston seafloor,” says ICA chief curator Eva Respini, who felt that Báez’s work was well-suited for thinking about the histories of trading, migration and cultural exchange along the Boston Harbor. “Here in Boston people might think ‘the Haitian Revolution really has nothing to do with me,’” she says, but points out it was the precursor to the abolitionist movement in the US.

Similar to architectural fragments Báez fabricated for the Berlin Biennale in 2018 and then recently for the High Line in New York, this seventy-two-foot-long, twenty-foot-high sculpture replicates the colonnades and corridors of the spectacular palace. Its faux crumbling walls will be stenciled with her interpretations of West African indigo printing patterns, appropriated from enslaved people in the American South, that Báez has embedded with motifs of resistance, such as the Black Panther logo.

The whole thing will be draped from the ceiling with blue industrial tarps, perforated to let in a constellation of light, creating the simultaneous effect of being under water and under the night sky.

“That site in Boston was one of the largest points of entry for people from other countries, almost a vetting into this new world,” says Báez. She is integrating sound into her work for the first time. Murmured voices, echoing stories of her own migration and of so many others, will be activated by people’s movement through the installation.

“This palace was built for a queen and was a place of joy and learning,” she explains, noting the presence of printing presses at Sans-Souci, meaning “without a care.” “If you’re going to build a new land and a new people, that’s what you would hope for. Even though an incredible earthquake destroyed it, it still resonates.”

in your life?

in your life?