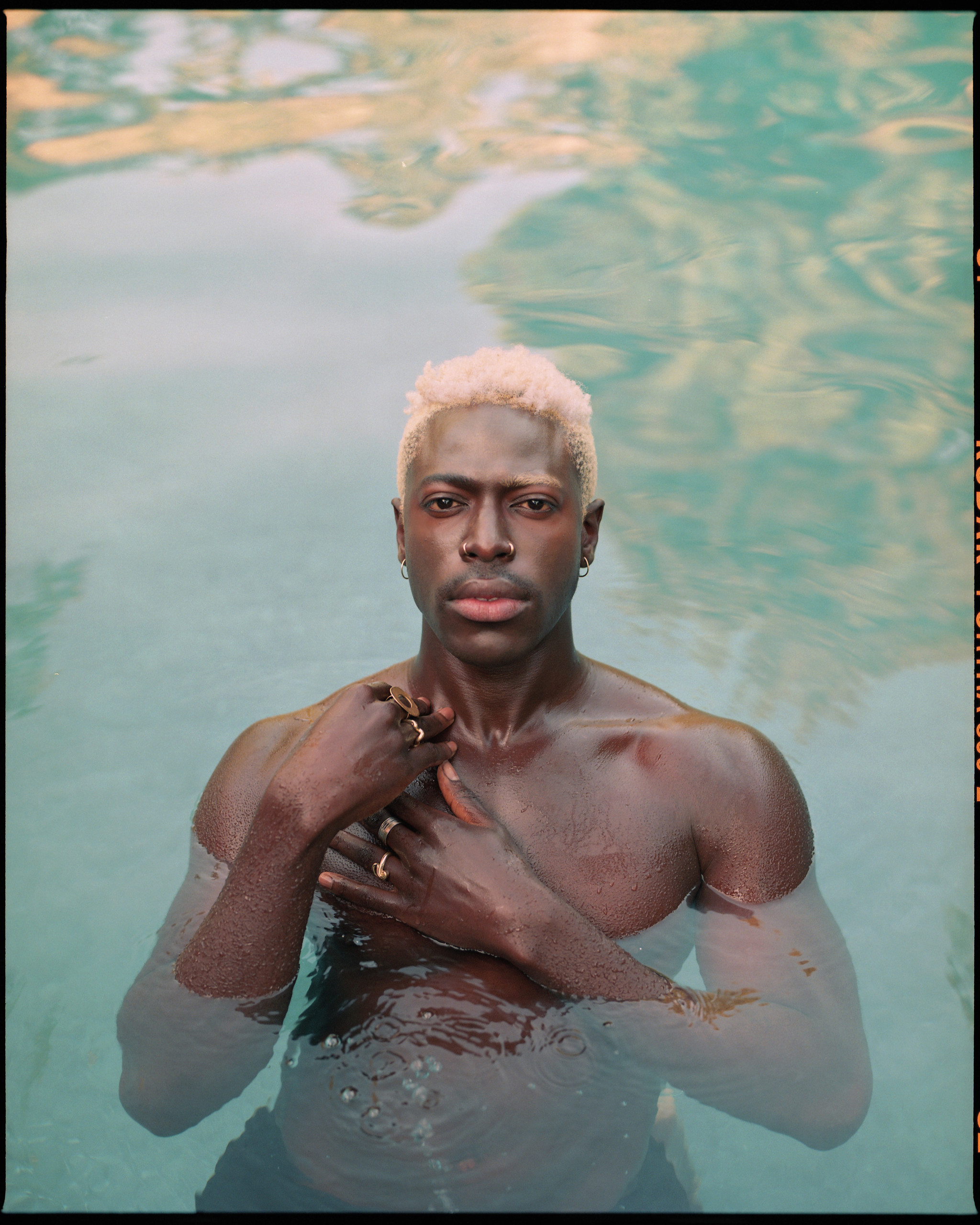

Caroline Polachek: You look so fresh with the short blond. Is it blond? Yes.

Moses Sumney: It is blond. It’s platinum blond-ish. I feel like a new person I had to change it up. It was time to refresh and just start new. New era, as the kids say.

CP: It’s a good time to. Where are you right now?

MS: I’m in Asheville, North Carolina, in my house, in my office-slash-studio, which is a mess. My view out of the studio window is really beautiful. I wish I could show you in person.

CP: I’m seeing terraced steps, beautiful greenery behind it.

MS: Yes, I live in a forest essentially. After living in L.A. for so long, living somewhere where the seasons change blows my mind. I’m like, “Whoa there’s leaves coming in!”

CP: It’s almost like when you get the flu or any sort of bad sickness, you suddenly have new access to the memories of all the other times you’ve been sick. Do you know what I mean? When it is spring, suddenly those smells give you like a renewed access to all your other spring memories. Do you find that?

MS: Yes. It’s as if there are chambers of memory and different points in time access different chambers.

CP: Fully. I think music can do that for people too, which is why people get so sentimental about music that reminds them of certain phases in their past.

MS: I’ve never actually actively thought about, but it is interesting to think that you would have to be in a really specific environment in order to experience a memory in a more visceral way, because of course you can remember anything at any point, but there’s also all the little things that you forget. I wonder where those go in your brain. For me, how certain plants smell or look or how many bugs there are in the spring, which I never remember.

CP: Maybe we can’t remember everything then. Maybe that’s a lie that we tell ourselves.

MS: Definitely, there’s so much that I just blank out on. I’m always surprised when I forget something, I feel like it’s gone forever. When it comes back, it feels really magical to me. I’m very forgetful. Then suddenly I’ll be like, “Hey, this thing.” I wish I knew more about science.

CP: How does it affect you when you’re writing? If you’re sketching the melody in the studio and someone you’re with starts playing something else, does it overwrite what you’re working on?

MS: Yes and I hate it. There is nothing worse than forgetting the melody. I only have capacity for one or two things at a time, one or two ideas.

CP: It’s so sad.

MS: It’s so sad because [when you’re writing] it’s like you accessed some magical channel. When you forget it, it’s like the channel has been sealed off. It actually kills me.

CP: It’s like you’ve pulled a little fish out of the ocean and then dropped it back and you’ll never see it again. It’s so sad.

MS: Absolutely. That’s not something I love.

CP: I was wondering if maybe this idea that we have access to all of our memories all the time is informed by our relationship with computers. This idea that everything can be backed up, that everything exists on the cloud, that everything exists in this logical objective way. We start thinking about our own brains and memories that way when they really couldn’t be any more different.

MS: It’s like we lie to ourselves more?

CP: Well, it’s almost like we think about information the way computers do. We imagine that our own relationship with information is similar to computers, but it’s just not.

MS: The irony of that for me is without computers, I feel like my memory would be much stronger. If I wasn’t relying on the crutch of, “Oh, I’ll just be able to access that at any point,” I’d work harder. It’s the simple thing of memorizing phone numbers. Back in the day, I used to know everybody’s phone number. Now the idea of knowing someone’s number seems psychotic. How creepy would it be if I was like, “Oh, your number is 823 472.”

CP: I’d feel touched, but maybe a little worried.

MS: Yes, exactly. I would be like, “Oh, that’s sweet, but why?” I think about this with writing too. The idea of losing a notebook to me is the worst thing that could happen because it’s where I write lyrics or just ideas. But of course there are people who used to just write up here, which is, maybe it’s a bygone era.

CP: They must still exist. That takes me to something I wanted to ask you about. I was having a conversation last night with a sculptor friend of mine and was saying that I really envied her relationship with her work, where her relationship with what she’s doing is contained in this object. As a musician, I feel like what we make is so ephemeral and exists in this digital space ultimately, but yet there’s this irony where what we do for a living, we can’t outsource to an assistant or to a fabricator, it has to come from us in our bodies. I feel like you’re maybe the artist who represents that embodiment for me more than anyone else I know, with how much care you put into presenting yourself and the physicality of your singing. Does that dissonance ring true for you at all or do you feel harmonized with it?

MS: Wow. I’ve never thought about that before, which is really quite a striking thing to sit with. I think that I was always really disturbed as a child by ephemerality of course, without knowing what that was. I was always really, really shaken by the temporal nature of time and I would almost obsessively try to perform tasks or movements just over and over, just to be like, “What if I did it again? What if I did it again? What if I did it again? Now, it’s gone.”

CP: I can do it again. I can rewind, I can replay.

MS: Yes, absolutely. Can I recapture time or an idea? I would think about this a lot as a kid and be really annoyed by the fact that I couldn’t. Really it’s all about death for me. All things, all paths lead there, which is inevitable and scary, but also there’s something comforting about knowing that it’s going to happen regardless. I think the way that that manifested for me vocally was just trying to create a rift in time learning to hold a note for as long as possible, or trying to do things that were really disruptive and felt like they were tearing through a plane, which they’re not and they can’t, but really putting everything into it and giving it everything made me feel better about the ephemeral nature of what I do.

CP: It’s amazing that you think about sustaining notes as a form of playing with time. I love that. It gives me chills. I took your entire discography for a walk today and it definitely stuck out at me how the more you work, the more of these obviously pronounced long notes are appearing. It’s cool to hear that’s the philosophy behind that.

MS: How long can we make a moment last?

CP: Speaking of long notes, this is very special that we’re two vocalists who get to speak about singing, so I’m going to really get into that.

MS: I don’t know that much about singing.

CP: No one gets to know anything about singing. That’s how it works. We’re just driving the car. For me, I have all these visual devices that I use when singing. For me, it feels very aerial, it feels like a bird in space, or I very often think about it in terms of drawing, even harmony as being like, “Oh, that’s a paintbrush instead of a pencil.” You’re moving parallel fibers in space. I’m really curious if you have any visual devices conscious or unconscious that you find coming up as you’re singing or as you’re writing.

MS: I almost don’t. It feels more in my body than in my mind’s eye. Obviously, I have visual things that I go to a lot when I’m writing. I think about color sometimes when singing. I think about temperature, warmth or what’s warm, what’s cool. What feels soft and what feels rough? What feels porous? I think about that a lot because I have a really raspy voice and it often feels like someone just poked a bunch of holes in it. You said you think of drawing lines sometimes?

CP: Yes, but I also went to art school for drawing. I think the way a point moves through space feels very vocal, but also what you do with your voice feels so environmental.

MS: Yes, that’s really important to me, to feel more like an architect or a director, and to be able to feel like every piece of the music is a reflection of me, whether or not I am the one playing it, and whether or not I am present as a vocalist or a storyteller in the explicit sense. I think about this all the time as a soloist. As a first name or last name artist, so much of your music becomes about your image, the idea of you is ever-present in the music. No one’s ever like, “Oh, and the bassist is—” Whereas when I think of a band, we love Cocteau Twins, and as much as I’m thinking of Liz Fraser, I’m thinking about the environment and I’m thinking about the atmosphere that’s created and I’m thinking about the different people and what they’re all bringing, or I’m not thinking at all.

As a result, I often feel the need to step away from my image and ego. I get sick of myself, especially because I sing so much on the record and in the live shows, I’m like, “All right, that’s enough of me. Really, we’ve had enough of that. How can we tell stories with just music? How can we tell stories with images? How can we tell stories with instrumental pieces?” Because that is just as much a part of it as me doing a few riffs or something. How can I bring in other people’s voices and stitch and patch them together? As soon as I started making films I’ve been thinking more about that, being a conductor, patching in different voices, and saying, “This is who I am as well.” It’s definitely something I want to do more. I’m always like, “Sing less.” Then I can’t.

CP: Maybe just the definition of singing is just shifting.

MS: Yes, I think it needs to because space is such an important part of singing, just in the same way that you have to take a breath. The moments you choose not to sing are just as impactful, if not more impactful.

CP: I think that’s the deep lesson of entering one’s 30s in general. Philosophically, just having that wherewithal, having that presence of mind to be like, “I don’t need to be speaking right now. Is it awful if I don’t?”

MS: Yes, totally. Often silence is also a mystery. Come on.

CP: Who’s one of your mystery icons? Who do you think is completely getting it right in terms of staying mysterious in 2021?

MS: In 2021?

CP: In 2021, who’s mysterious?

MS: Damn.

CP: Can mystery survive this year?

MS: That’s also a great question for last year. It was a moment where everyone was like, “Here’s me in my house.” And it’s like, “Do we care? I’m not sure we do.” Honestly, I have to say Beyoncé is the queen of mystery, the queen of candor, and giving. I would call it generous mystery. She gives you so much and at the end of the day, you don’t know shit about her. You don’t know shit about her life. I think that’s fucking cool because it’s still so generous. Who else? I’m going to think about it because I want to say more names. I want to put that question back to you actually.

CP: I think Yves Tumor walks that tight rope. Who else?

MS: I agree wholeheartedly.

CP: We’ll do a mystery round two at the end, but then round two has to be non-musicians as well, if you can think of any.

MS: I’m jealous you said Yves Tumor and that I didn’t say it to be really honest.

CP: Maybe we just leave it as Beyoncé and Yves Tumor because that’s a hot duo of mystery masters.

MS: Great range.

CP: I want to jump topics for a second. You talk about plurality in “græ” and you also embody it so deeply in that album. I’ve been thinking a lot about archetypes and how these archetypes that we’re raised with inform us again and again and again, both as things that we don’t want to be perceived as and things that we deeply cherish and are constantly seeking to arrive at in our own way. I’m curious about any archetypes that you encountered as a young person, younger than 12, and not necessarily people that you wanted to become, not role models, but ways of being that you found in the world that you were deeply attracted to and still engage with. Are there any archetypes that are very meaningful to you right now?

MS: Yes. I’m obsessed with the introvert archetype, the bookish introvert, which I am, but not fully. I’m not nearly as bookish as I wish I was, but as a child, I was extremely bookish. I would go to the library every Saturday and check out 15 to 20 books. My goal was to read them all before the next Saturday. Actually, I was quite lonely as a child, but that was maybe actually another archetype that I was attracted to, the loner. The You-don’t-get-me kind of mysterious loser was one I absolutely loved as a kid. I would say those are the two that I’m still very attracted to. Then I get really envious when other people say, “No, I don’t leave my house.” Or people are like, “Oh no, I read two books this week.” I’m like, “How?”

CP: I have memorized your phone number suddenly.

MS: Yes, exactly. “I’m calling you from my rotary phone.”

CP: Oh, that’s so beautiful. Those archetypes do come up so much in the idea of outsider and experimental music in general as well. I wonder sometimes if those archetypes are what drew us to that music in the first place. We’re like, “Oh, that’s what those people listen to.”

MS: Exactly. That’s the coolest type of person, the kind of person that goes off and does their own thing and then makes whatever they make unaffected by the mainstream ideal of what they should be doing. It’s like, “That’s who I want to be following. The person who’s creating outside of culture.” Because those are often the people who end up making cultural shifts honestly.

CP: Yes, totally. The loner is always going to be someone who has the confidence to be alone and also has some skepticism about what else is going on or has nothing better to do and that’s just an intoxicating combo.

MS: It is because you should be skeptical.

CP: I have an assignment for you. Do you have your phone around?

MS: It’s sadly right here.

CP: I want you to find your last selfie and describe it really poetically.

MS: Oh, my God. This is a great assignment.

CP: You can also lie. You can blatantly lie, but we’re here for the poetic description of your last selfie.

MS: Off-the-cuff poetry. I don’t know. I’m a little rusty. Let’s see. Luxuriating on lamb skin. A rug, a bag made of calfskin, sheepskin sits on its calves next to me, also on top of the lambskin. It’s lamb on lamb and I am laying down next to it gazing quite forlornly into the mirror. Phone next to my head, sunglasses on though it is nighttime. You can’t see my eyes, but I’m gazing, gazing, gazing.

CP: “Lamb on lamb?” If that’s not the title of this interview, I don’t know what is.

MS: I’ll send it to you.

CP: Thank you for that. Yes, please. If you don’t mind me asking, who was the photo taken for?

MS: The photo was to my friends, Matt and Kelly, who worked for Thom Browne. They sent me this gorgeous bag for my birthday, which was a lamb. My birthday was yesterday.

CP: Happy birthday!

MS: Thank you. Although I say I wasn’t born, I landed.

CP: Whilst this is a beautiful photo, your description of it painted, I imagined, a fireplace.

MS: Oh my God.

CP: No, I imagined stacks of dusty books. I don’t know why.

MS: No, I love that. Your imagination will always be better than the real thing.

CP: Well, I’m going to fill in some of the blanks. This wooden mirror is propped up on a wooden floor next to a dark gray floor-to-ceiling velveteen curtain that matches the exact shade of muted gray of the wall behind Moses. It’s modern. This is a modern room.

MS: Very true. I love that exercise. Thank you.

CP: I’m going to switch once again and bring us back to your past a bit. I’m curious about your first ever memorable experience writing songs. How old were you? Did anyone hear these songs? Where were you?

MS: I have two distinct memories. Actually stories I haven’t really told, but the first one was when I was seven and I knew I wanted to be a singer. I had watched a movie. I don’t remember exactly what it was called. It was called One-Night John or something like that. I wrote a song called “One-Night Stand”—where I learned the phrase, I don’t really know because I was seven years old. I’d written it and it was the lyrics were like, “The one-night stand for a one-night man. Something I could never do.” Did not know what a one-night stand was. “One night stand for one man. What and who.”

I had written it as a whole thing and I took it to school and I just held it very close because I was like, “Wow, I wrote a song,” so special and then I lost the paper at lunchtime. I grew up going to a Christian private school. I lost the paper and some older kids found it. Kids who obviously knew what a one-night stand was. I could see them at a lunch table laughing and just being like, What the fuck? Then they gave it to the teacher and told on me and the teacher came to me, took me aside and was like, “Moses, you’re a really good kid and this is not what I expect from you. I could really tell your parents, but I’m just not. Just don’t do that again.”

CP: So sexuality, in general, was not accepted at that age?

MS: Yes. It was the sexuality and that age and the fact that it was a Christian school. I didn’t know that it was sexual. I was just like, I don’t really know what I did wrong but clearly I pushed a button, so there’s something here.

CP: Wow. I think that would have really traumatized me, actually, as a kid. That’s cool that you leaned into being provocative.

MS: Well, I think I’d had both experiences but I leaned into wanting to provoke, but I also wanting to be even more private because I hadn’t told anyone. Remember I didn’t really have friends. I wasn’t like, “Hey, I wrote a song.” I was more just like, “This is a thing I did by myself, for myself.”

The second memory I want to tell you is years and years later. I didn’t write another song until five or six years later. It was five or six years until I picked up the pen again. I was now living in Ghana. That first story was in California. This second story is in Ghana. I had a friend, like a best friend, and he knew I wanted to be a singer.

We had a weird relationship, I would say we weren’t real friends, it was one of those school relationships where you’re super competitive and you’re like, “I love you but I also want to destroy you.” He one day was like, “I wrote a song.” I was just like, “Oh.” And then he was like, “Yes. I don’t know, I was just chilling last night and I wrote a whole song. Want to see it?” He showed me this whole song that he had written and I was just so jealous. I was just like, “That’s my thing, I’m the songwriter. Have I been writing songs? No. But I am the songwriter amongst the two of us, and I’m the singer. I’m going to start writing songs.” I went home and I started writing songs. I wrote my first one and I came back. I remember this song was called “Mesmerizing Eyes”, it was a love song. Who was I singing to? No idea.

I came back and I was like, “I wrote a song. Blah, blah, blah.” He had completely forgotten about it. He was like, “Oh. I was kidding, I didn’t write that song. That was a Westlife song.” Do you know the band Westlife?

CP: Yes.

MS: He was like, “Oh, I’d forgot—Oh, that? That was a Westlife song. I don’t write songs.” I was like, “Oh,” but then it just actually triggered this thing in me where I just never stopped writing songs after that. I was always writing songs after that.

CP: How did you write that song? Was there accompaniment or was it just a cappella?

MS: There was no accompaniment, and the first, I would say seven or eight years that I wrote songs, I primarily wrote them a cappella. I did not know how to play any instruments, and I came from a family that discouraged music-making. I, in a really insular way, would just write songs alone in my room. I had a notebook that I would write all the lyrics in and I would just remember all of the melodies. At the peak of this, I had 100 songs in this notebook. This is actually what I was saying about pre-digital songwriting. I had 100 songs and I could sing you verbatim verse, chorus, bridge, verse, chorus, bridge, every single melody, without ever recording them and without ever having a reference pitch.

CP: That is so beautiful. Would you ever consider going back into them? Do you still have that writing anywhere?

MS: I hope I do. I think it’s in a storage unit somewhere. I remember some of the songs still. I am interested in revisiting some of them lyrically. I know I have to change some lyrics. I don’t know what the lyricism was doing. Melodically I am interested in revisiting them because I was very much writing pop songs. I was very much pop, R&B and rock but I would put them all under the umbrella of pop. I think about it sometimes and those are my roots as a songwriter. Then I went into this place of wanting to be more experimental and abstract and obscure, of course. I wanted to be an artist. I am interested in revisiting them but also I’m curious to know what I would do instrumentally now that I have the skill and the knowledge that I have.

CP: That would be such a wild experiment. It’s funny because my first interest and I mean addictive, obsessive interest in music came from pop music as well, probably at the age of eight or nine. Then, of course, once we entered our early teens we started finding out about Radiohead and then: Mind equals blown. Then we go down that hole. It’s funny that you describe these a capella pieces of music as pop tunes, when I think, for me, the music that gets described as pop music now is music that’s incredibly produced and especially very electronically produced. It makes me think that maybe pop tunes, the tunes that are singable in the schoolyard, in the back of the car without any accompaniment, are folk music and that’s what folk music has always been. I’m curious about your own relationship with that term and that idea.

MS: I think that what we think of as folk music, from a modern cultural perspective is not as expansive as folk music actually is and was going through the ages. I love the idea that the only way to capture a memory is to write it. I think that idea in some ways is at the foundation of pop music because in order to pass on that oral history it has to be memorable. It’s got to be catchy.

CP: That’s so interesting to use a narrative form as a definition of folk music. The way I’ve always thought about it has to do with the economy of what’s available, like using instruments that are easily accessible. Whether it was a lute or a bottle, or a guitar or a computer. By that standard of defining folk music then, would you include love songs in that? They’re not talking about the times as much as they are about a personal feeling.

MS: Yes, absolutely. I would. Traditionally, those are also passed down. We are talking about how something felt and how it looked and how it smelled and tasted and needing to share that with someone else. We have an idea of the love song before we have an idea of what love itself is. I know that was the case for me. I was writing love songs before I even had tried to imagine myself being in love.

CP: I guess Greensleeves is probably the oldest folk song I can place. That’s a love song, isn’t it? I can’t recall the lyrics.

MS: Yes: “Alas, my love, you do me wrong.”

CP: Right there, line one.

MS: It says traditional English folk. Henry VIII of England, 1500s.

CP: We’re including heartbreak in oral history. That seems right.

MS: Also, what could be more universal? There’s both capturing a moment, but there’s also an implied universality to the folk song, the pop song, and those are the most universal timeless tropes.

CP: The love song too. I had this switch flip inside me a few years ago when I started listening to love songs as spiritual instead. If you think about the you in any love song as being life itself, it just changes everything. It’s pretty amazing.

MS: I need to sit with that because that is really deep. I had the inclination as a child, but even now, sometimes an inclination to listen for a “you,” when there isn’t one. Where does that come from? It’s true that there is some kind of inherent spirituality to the romance of being. Often that’s what you’re tapping into. It’s about the actual romance of just being alive and listening and taking things in and feeling. Are there any specific songs that made you start thinking about that, or was that more in the songwriting process?

CP: I can’t remember what actually triggered it, but I got very critical of my own use of the word “you” in songs—that I was leaning on it too much as a device. I was starting to question if there was any kind of implied femininity in making so many songs dedicated to or about people. There’s this whole history especially within 1960s protest songs of talking about ontology. What exists in the world, what’s going on in this shared space? The politics, the facts of living, what’s going on in the neighborhood. I was just thinking about that legacy belonging more to men in the last century than to female songwriters. Then I started getting really critical of my own use of direct subject in music and trying to push myself out of that, into writing in a more ontological or abstract or socially conscious way, and ultimately failing at it. I’m a romantic, I’m a hopeless romantic, and I decided to detach that from any idea of gender and put all those critical thoughts away and redefine “you” as a living itself.

MS: Honestly, I’m glad you just touched on that because I feel similar in some ways because especially with my first album, I felt so dominated by the culture of romance and obsessed with it, even as someone who felt like I was on the periphery of it. Standing outside the club, listening to the music and the bass but not actually being in the club.

CP: Have you gotten down to the rabbit hole of this YouTube genre of people rerecording albums from outside of the club?

MS: I fucking love those rerecords. I felt similar to you in that I felt like so much of my writing was about romance or love or the lack of love or infatuation. I was like, Damn bitch, can we come up with something else? Is there more to life? Then I’ve written a bunch of songs that aren’t but it honestly just doesn’t hit the same, it doesn’t hit the same as writing to you. There’s something about it.

CP: I think we’ve peaked, but I still have a couple of questions. In this digital age of music release, which you’ve experienced so personally because you’ve put out a record during a time you couldn’t tour it, where we’re left feeling very on our own in this monocultural digital soup that is the internet, it seems to make the need for mentorship much greater. I was curious if you have or had any mentors in your career, or if you’ve ever considered mentoring younger artists yourself?

MS: Yes and no. I was actually thinking about this a few days ago. I don’t feel like I have any mentors and it bothers me. Maybe it’s me. I’ve never really been the type of person to let’s say, seek out apprenticeship. However, I can point to certain people who have been there at different points in my life, who gave me advice and I could learn from. I would say that Dave Sitek, the producer from TV on the Radio, was a big one. Early in my career he gave me great advice about navigating labels and navigating producers. It was a big thing to produce my first record. I was meeting all these white male bros. He gave me really excellent advice about going my own path and doing my own thing and I never forgot it.

I also toured with Sufjan Stevens before my first album came out and he was really great. Again, really generous and kind, and a great ear.

CP: That’s interesting to think about support gigs as a form of apprenticeship.

MS: They could be but they usually end up being traumatizing.

CP: I had so many of those, going out on the road, opening, I will not name any names, but opening for lots for artists who just barely wanted to speak to me. Then the opposite also happens too, where you’re opening for someone every night and you just watch and learn.

MS: A lot of it does end up being you just watch and learn, as opposed to, “Hey, can I ask you a question?” It’s rare that established artists will take the time. Most of the time you get bullied as a support act. You get tossed around. I hated those days, but yes Sufjan was very much like, “Hey, what are you doing? How’s it going?”

I would say Solange was another person who’s been really generous and open. I’ve had people along the way who have given me wonderful advice but I wish that maybe I had sought out someone to be like, “Hey, can I just really sit and learn from you? I don’t know shit. Can I come to you and just ask you stuff? Can I just sit behind you and watch you as you produce? Can I just sit there and maybe ask a question here and there, but I won’t be annoying.”

CP: I wonder if, as you were saying, you’re attracted to this archetype of the loner which actually predisposes us to be musicians in the first place, so as much as we’re the kind of people to not ask for help maybe we don’t need it either.

MS: I think it’s both. Everyone needs help, but I think that you don’t need help all the time. Let’s say that. We’re sitting in our rooms teaching ourselves how to do things and exploring our own curiosities and not knowing the right way to do this is part of what makes it more interesting anyway. I agree to taking advice on the business side of things, because it’s so mysterious.

CP: Speaking of mystery, do you have a final mystery icon?

MS: I’m thinking of this French actress actually. Isabelle Huppert.

CP: The ultimate. I just thought of mine, but it’s really contentious. Have you seen Barron Trump’s artwork?

MS: Wait, what?

CP: I think he’s like 12 years old, but he makes these really horny anime drawings that are actually kind of good—

MS: Wait, I’m looking this up immediately.

CP: But also that classic photo of him in the backseat of a limousine, that should’ve been an Evian Christ album cover. That should’ve been the cover of the darkest album of the year. It’s an open goal. Anyone reading this who needs album art, just snatch that image because it’s timeless.

MS: It’s so good.

CP: That’s not crafted mystery, that’s a mystery for a very different set of reasons but equally potent.

MS: I’m just blown away. You know what I mean? I’m almost just like, “What’s going on in there?” I would love—

CP: There’s probably some really good fan fiction.

MS: Actually, to that end, this is a little bit less supportive but just because now it feels fun: Ella Emhoff.

CP: Oh crazy. It’s so hard to know if she’s actually compelling or if the situation is just so wild and loaded, but it doesn’t matter anymore, does it? It’s all one thing.

MS: It’s all one. That’s what is great about it. It’s all just mashed together and we’re just outside the club listening to culture audio.

CP: We’re eating the culture sandwich.

MS: We really are.

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.

in your life?

in your life?