Celine Song doesn’t agree with my assertion that her sophomore film, Materialists, is a “bigger production” than her Oscar-nominated debut, Past Lives. In fact, she doesn’t seem to agree with most of my statements about the movie—a sign, at least, that Materialists has enough depth to prompt healthy debate.

In 2023, Past Lives hit theaters like a missile calibrated for maximum career impact. The Best Picture nominee took Song from off-Broadway playwright to household name (at least among cinephiles), and its lead actress, Greta Lee, from supporting TV actor to the face of Tiffany & Co.

Song’s story of a semi-autobiographical love triangle between Lee’s character Nora, her childhood friend Hae Sung, and her husband Arthur was suffused with quiet longing. So when Materialists’s tri-love story came about, fans were ready to proclaim Song a master of the genre. Yet the filmmaker insists that her first film was not, in fact, a love triangle. “It’s about this woman who is contending with reconnecting with her childhood sweetheart,” Song says. “This movie, unlike Past Lives, is actually a love triangle.”

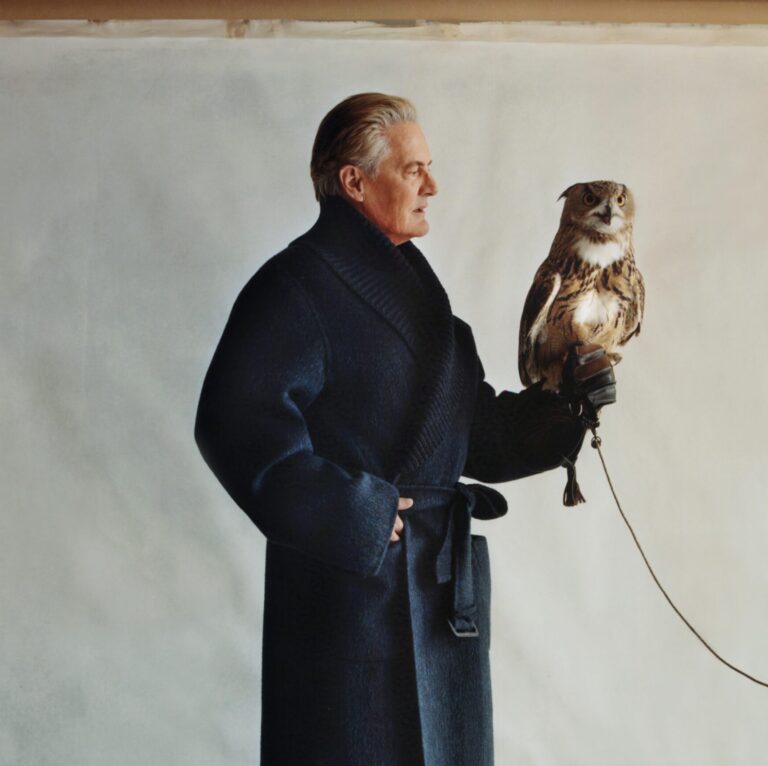

Materialists tells the story of a New York matchmaker torn between two paramours. Its triple bill undoubtedly caused a studio exec somewhere to weep tears of joy: Dakota Johnson is the lead, Chris Evans is her perpetually broke ex, and Pedro Pascal is what Johnson’s character, Lucy, calls “a unicorn.” He’s rich, affectionate, tall, mentally stable, and, well, he looks like Pedro Pascal.

Song shrugs off this boost in name recognition—and budget ($12 million for Past Lives vs. certainly more than that). “I think of it more in terms of the scale that is required for the story, more than ‘bigger project, little project,’” she says, “because every project is the biggest project in the world for me. It’s my whole life.” Where she and I do agree is that, despite cursory similarities, Past Lives and Materialists are not the same beast.

The plot of Materialists is inspired by the six months Song spent working as a matchmaker in New York to support her burgeoning career in theater. “I was hearing sides of these modern working people that I don’t even think their therapists would hear,” she recalls. “They’re describing [a partner] to me like they’re describing a dream car.”

It’s a sentiment that comes through in the film, too, as Lucy listens to men asking for skinny 20-somethings and women seeking tall, rich men. The tension becomes even more explicit as Lucy is forced to weigh the type of man she says she wants (Pascal’s character) with what she can’t help but feel drawn to (Evans’s character).

Online, responses to previews of the film were swift: Song was on her way to save the rom-com. We’ve heard that distinction given to directors year after year as audiences look for something to scratch that mid-2000s itch. I’d argue they aren’t going to find quite what they’re looking for here. Despite the twinkly music and baritone voiceover of the trailer, Materialists isn’t a zinger-packed, 90-minute marvel. True to Song’s introspective bent, it’s a quieter meditation on what we really want out of love.

The film opens on a still canyon where a prehistoric couple emerges and stares longingly into each other’s eyes. In the theater, I suspected that I wasn’t alone in wondering if I’d somehow stumbled into the wrong screening. “That’s what I wanted!” Song says. “Right from the start, it’s a rom-com, but it doesn’t necessarily have the pacing or the affect that people might expect.”

Materialists has all the cool detachment, cynicism, hopefulness, and careerist striving of the New York dating scene itself. Lucy—who grew up hearing her parents fight over finances as they sought to ascend tax brackets—draws out her clients’ underlying desires with an ease her coworkers find almost preternatural. Smoking on the fire escape, she vows to marry rich or not at all. But when faced with the opportunity to do just that, she levels Pascal with a steely gaze and tries to reason away his feelings for her. “What are you doing with me?” she wonders aloud.

This straightforwardness, at least in the first half of the film, comes across as more protective than soul-baring. If Past Lives was about the inherent honesty of real intimacy, Materialists is more focused on the red flags and self-rationalizations we construct to avoid it. We’re confronted, repeatedly, with the callousness of modern dating.

“To me, Materialists is as honest as it gets,” argues Song. “When we’re talking about relationships and connection, you’re always playing with intimacy and distance, right? It’s not one night for them in a way that it might be in Past Lives. [Marriage] is going to be forever. They have to be like, ‘Why do you love me? Tell me.’”

Indeed, as in Past Lives, many of the most affecting scenes in the film come in the form of one-on-one heart-to-hearts. But while Song got bigger actors for this film, she didn’t necessarily get better ones. Just as Materialists suggests Pascal’s private equity manager isn’t necessarily the better option just because he has more in the bank, Johnson and Evans’s star power and Hollywood gloss don’t necessarily convey the depth required of characters working through deep-seated fears about love, loneliness, and class. (Pascal, for what’s it’s worth, delivers when it’s his turn to take center stage.)

Despite occassionally flat deliveries, contrived lines, and predictable turns, Song’s sharp directorial eye is evident. Like Lucy, her keen observations and attention to detail are undeniable, from the heel-clicking charge of bridesmaids that had my audience in peals of laughter to the perfect stretches of quiet that permeate the action. Even if it’s not as startlingly brilliant as Past Lives, Materialists offers something perfectly enjoyable—a more difficult feat than one might expect for a sophomore run.

“It’s a beautiful thing that all we get to do, to spend two hours talking about love,” Song says. That alone could sum up Song’s career thus far—she’s a filmmaker who seems primed to join a developing canon of 21st-century relationship auteurs.

Is she ever tempted to take on a different subject? “Love is one of the most mysterious things,” she says. “I’m going to always be drawn to love stories. But it can be in any kind of form.”

That’s one thing the two of us can agree on before our time has run out: I want to see another film from Song.

in your life?

in your life?