With a growing list of galleries closing in New York and beyond, the contraction of the market has rattled the art world.

We can’t say, however, that we couldn’t see it coming. Recent history shows a remarkably consistent pattern of expansion and correction. Roughly every eight years, it seems, galleries are hit hard by the market’s inevitable decline after periods of explosive growth.

In the wake of 2008’s financial collapse, around two dozen New York galleries shuttered, according to the New York Times. Fast forward to 2016, and it happened again—a wave of more than a dozen gallery closures in 18 months. News reports blamed the closures on market oversaturation, speculative buyers, exorbitant New York real estate, and the rising cost of fair participation. Young and midsize dealers who had dramatically expanded their overhead during the preceding booms, for fear of stagnating or losing their artists to bigger galleries, found themselves with operations larger than a declining market could support.

“There was too much art, people were exhausted by too many fairs all over the world and every dealer had the same contacts on their lists,” Lisa Cooley told the Financial Times, having just closed her gallery on the Lower East Side. Her sentiments sound astonishingly familiar.

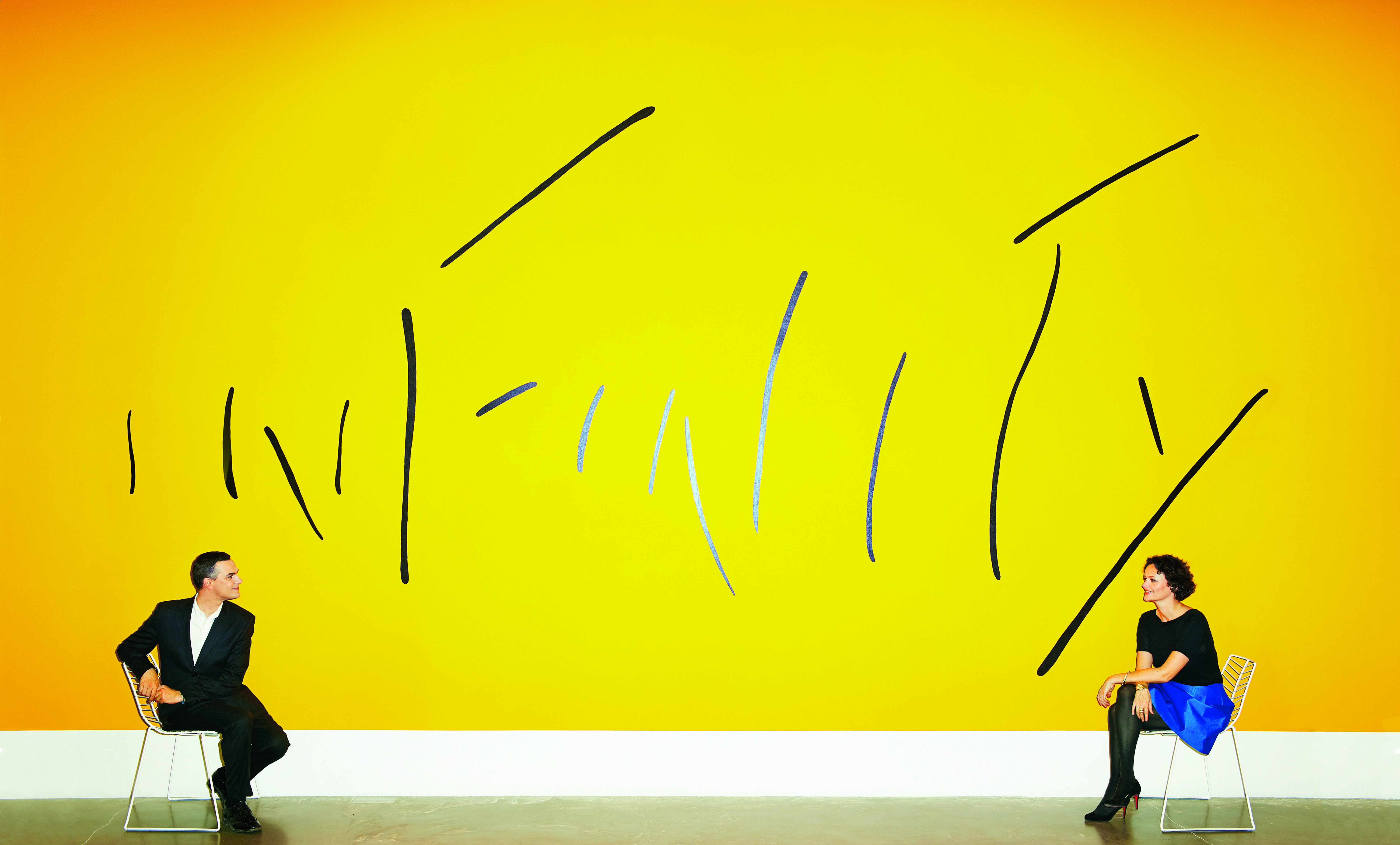

In the predictable boom-and-bust cycle of the art market, what goes up must come down. But do galleries necessarily have to go down with it? CULTURED posed the question to Candice Madey and Laurel Gitlen, two New York gallerists who shuttered their businesses after the 2016 contraction and restarted them again in recent years, older and wiser.

Like Cooley, both gallerists opened on the Lower East Side in 2008, as the neighborhood flourished between downturns. Gitlen closed in 2016 and reopened in 2022, and Madey closed On Stellar Rays in 2017 before opening her eponymous space in 2020. Reflecting on their trajectories, each discusses how galleries can prepare themselves for inevitable downturns and considered the potential upsides of market corrections.

“The last crash opened the art world’s tightly guarded gates to a wave of upstart talent and radical new ways of thinking,” Holland Cotter wrote shortly after the crash of 2008. “That was great. It could happen again.”

Janelle Zara: What was it like opening on the Lower East Side in 2008, when so many galleries were closing? It seems like the neighborhood really thrived commercially between downturns.

Laurel Gitlen: Our move to New York [after three years in Portland] corresponded almost exactly with the Lehman Brothers collapse. The emerging market was pretty strong in those years; collectors still wanted to buy art, and the entry point to collect was like $2,000 to $3,000. It had a lot of collaborative energy—we were regularly walking our clients over to neighboring galleries and vice versa. The shows were ambitious, and our overhead was pretty low. It was a very fun time.

Candice Madey: I think it was advantageous. I had very low sales expectations to begin with because I was so new, so it wasn’t easy, but I managed to hang in there by making money consulting on the side.

Zara: Looking back to 2016, what was going through your head as you decided to close? Both then and now, there seems to be a pattern of galleries expanding to a point that became unsustainable.

Gitlen: It wasn’t so dramatic. There was this super-strong period from about 2010 to 2013 when gallerists on the Lower East Side were really focused on the aggressive expansion of our programs. I moved from a 500-square-foot space to a 2,000-square-foot space, and we had the sales to back that up. But when the market slowed, it had gotten to the point where if I sold nothing that month, I’d go $50,000 into debt. Could we have kept going? Yes, when we closed, we had some really successful painters like Emily Mae Smith and Ryan McLaughlin. But the financial pressures were getting really stressful, and it just wasn’t pleasurable anymore. When a much bigger gallery offered me a lot of money to sublease our space, I realized I could just pay all my bills and walk away.

Madey: I’ve been through that—expanding and getting totally overwhelmed, not even financially, but in terms of how much one can handle, or how much energy a person can put out. When I closed On Stellar Rays in 2017, I had just signed on to a very expensive space. With Trump’s election and feeling like the world was ending, I knew it just wasn’t gonna work.

Zara: How much does real estate play a role in making or breaking a gallery?

Madey: Moving into a bigger space takes so much mental and economic energy away from the program. Rather than growing big and getting stuck, we’ve set ourselves up for expansion and contraction. I’ve experimented with second exhibition spaces at different points in the gallery’s history, but I’m not in Tribeca: I’ve been at my space on the Lower East Side since 2013 [Madey kept the property after closing, subletting part of the space and using the rest as an office]. I know that no matter what happens, I can manage the rent.

Gitlen: A Tribeca storefront has a great built-in audience, but if you have 10 shows a year and only two or three make money, your space becomes such a burden. My main thought when I reopened was to lower the pressure by lowering my overhead, so I chose a weird, small, incredibly affordable space [in the Lower East Side] that allowed me to do more experimental shows—a single video by Katz Tepper, or a single sculpture by Peggy Chiang. I’m currently between spaces. When they told us they weren’t offering us a new lease in June, I decided to take it slow, especially with the current market. Right now I’m organizing two shows in a domestic setting in Bed Stuy, which I might not have done at another moment. Now there's no reason not to, especially because so much of our sales are online and by appointment.

Zara: How does today’s market compare to previous downturns?

Madey: This isn’t 2008 or 2009, when sales just stopped. It’s more that sales are so far below expectations and at lower price points. Instead of the $48,000 piece, I'm selling the $15,000 piece, and our costs, including photography, local shipping, packing, and framing have gone up with inflation in ways I couldn’t have anticipated. Where you’d think that getting a big work from Brooklyn would cost $600, tops, I get a low-end estimate for $2,900. The volatility is really hard. You could make everything more expensive, but you might not sell it.

Gitlen: The main difference to me is that in 2012 and 2013, there was a robust market for diverse, challenging practices; I could sell giant sculpture and long-format video. But when I reopened in 2022, it was immediately clear that the market was so focused on painting, and the attention cycle for an artist seemed to only be one show long. After our first two years, we went from reliably selling out shows to selling almost nothing. In my opinion, things are much worse now than they were in 2016. The market was already diminished by the fact that people were only selling very commercial work, and now even that’s not a sure thing.

Zara: Do you feel better positioned today to weather a downturn? Since reopening, what kinds of expenses have you cut in order to make your overhead more flexible?

Madey: I’ve been really cautious in terms of expenses. Part of staying nimble has been returning works to artists that I didn’t sell. It can be awkward, maybe, to admit that we didn’t find them a home, but for smaller galleries, the cost of storage can be crippling. I learned the hard way with On Stellar Rays. I also went several years without doing fairs, trying to think outside the box in terms of other ways of promoting artists; I launched an online editorial project called Journal, for example—a small investment [that] has had varying degrees of success. I am going to Art Basel Paris this fall with the estate of Darrel Ellis in a shared booth with Hannah Hoffman; collaborations like that have been so fundamental to my new operation. The collective energy of sharing costs, pooling resources and contacts, and generating attention together really energizes me. And in some cases, it’s increased our success tenfold.

Gitlen: I don't think anyone knows the answer at this point—how to navigate the increasing gap between how much you're spending versus how much you're making. Fairs are what I’m most ambivalent about. If you lose money, you can lose a lot of money, but at the moment they seem to be the only reliable mechanism for sales. I find the excitement of a fair is also hard to replicate; Peggy Chiang had six or seven studio visits with major international curators after we showed her work at Liste. For a small gallery, it’s hard to get that many eyes on your artists otherwise.

Zara: Having already been through a market downturn, what have you learned about resilience and sustainability?

Gitlen: Everyone knows that when there's this really buoyant, speculative market, it's going to be a disaster, but these situations are also an opportunity to function better as a community. People are coming up with more DIY, collaborative projects, like Esther, a non-traditional fair with a participation fee of $1,000, or the Campus, this collaboration between six galleries to show large-scale work. These feel like different ways of working, of putting our skills together to build something significant. Since coming back, I try not to think in terms of the gallery’s career trajectory as much as creating a community—one that works for artists rather than for the market, which is a trap that only works in the short term. The challenge now is cultivating young collectors so that dealers can support exciting practices; when dealers only show what people want, we all get bored.

Madey: Looking back, I realized the times I had money to pay myself generously at the end of the year were when the gallery was small, and the moments that looked really ambitious and impressive on the surface were when I was really struggling. It takes discipline to not get big, especially when that seems to be the goal, but you can’t really do all the interesting projects you want to do when you have a volume of sales to maintain. Don’t think of it as just an upward trajectory, but more like breath, a constant expansion and contraction. You inhale and you exhale.