Catherine Opie works a crowd like a seasoned tour guide—a historian intimately versed in her subject matter and equally fluent in the language of interpersonal connection. As she guides a small group of visitors—journalists, collectors, academics—through Regen Projects’s Los Angeles space, these two skillsets, rarely so intertwined in one artist, shine through. “Harmony is fraught,” the photographer’s latest exhibition in her adopted hometown of Los Angeles, marks her 30th year with the gallery, and her enduring role as a stalwart archivist of the city’s changing architectures—social, domestic, and public.

Opie attributes her knack for effortless connection to her first calling. “I was a camp counselor for way too long,” she says, “until I was in my 20s. And I loved it.” Decades of teaching at UCLA came much later, but kept the flame of youth alive. Despite the photographer’s bright, open, and somehow ageless affect, “harmony is fraught,” is born of the kinds of milestones that come with age: three decades with Regen Projects; the end of a 21-year relationship with her wife, Julie; the culmination of her teaching career; and the beginning of her son Oliver’s journey into the art world.

“I’ve never really shown the kinds of personal photographs that are in this exhibition,” the photographer muses as she stands before an image of Downtown LA’s Sixth Street Bridge—an undulating structure designed by her close friend, architect Michael Maltzan. Images of the city’s infrastructure appear on the walls alongside portraits of family in all its forms: lovers, friends at clubs, snapshots of queer domestic life. For Opie, these landscapes and nudes are equally personal. “This work is looking at my relationship to Los Angeles as infrastructure, and the queer body is an infrastructure as well,” she says. “You have these diaristic, intimate portraits and still lifes surrounded by images of the city that is nurturing them.”

To mark the opening of “harmony is fraught,” Opie walked CULTURED through the exhibition, offering a glimpse into the most treasured moments she has shared with the denizens of Los Angeles—and the city itself.

No galleries found for this post.

“This is, in a way, a self-portrait. When you come up to this medicine cabinet, shot with an eight-by-ten negative, you have every single detail of my ephemera perfectly framed. My work throughout the years has dealt with the idea of inside/outside. That has a lot to do with visibility and representation of the queer body.

So, my mustache is up above. Even though I wear a mustache when I go out and play with gender, I still bleach my own mustache—there’s the bleach. And there’s the relationship of the dildo, the vagisil, Preparation H, and a clay mask. In a way, all of these little things amount to a person that arcs across to the following photograph of my lover Pam, and sunday morning sex. Now, the things that you see in the medicine cabinet are all across the floor."

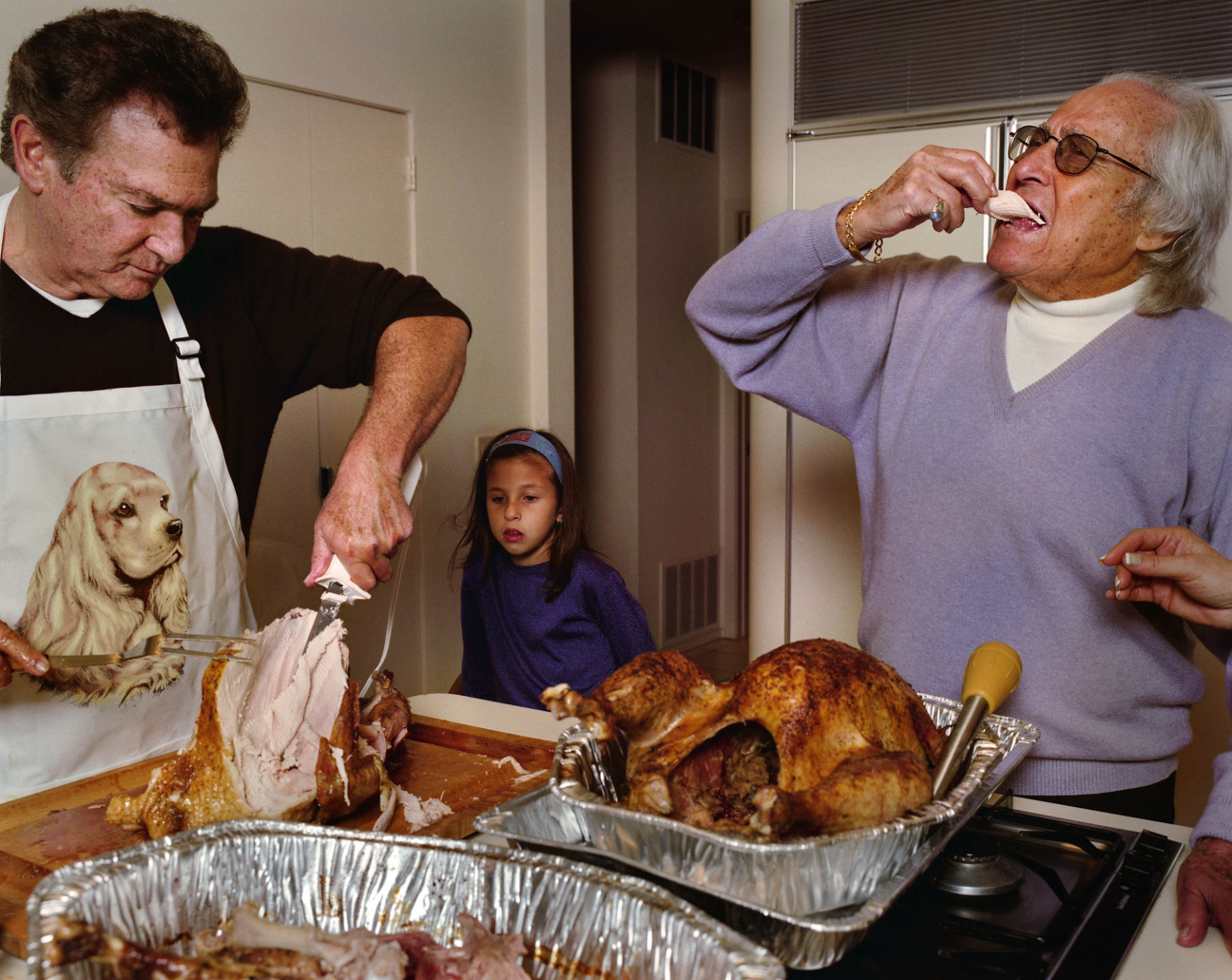

"Well, here’s Oliver and the turkey. There he is with the Thanksgiving turkey, so big. I always wanted family. I always wanted a kid. Whenever Oliver appears in the work, that work is one of the nearest and dearest to me. He's 21 now, he's about ready to graduate from college. It felt good to include him in this, because this show is about families. Look at him. At one-and-a-half, he already knows how to do a Cathy Opie face in a portrait. He was already intimately familiar with my work, because our studio was behind our house in West Adams."

“This is such an important moment for the city. Although I see myself as bearing witness or documenting these moments, they're not journalistic photographs. I’m more interested in the question, How do these moments in our shared life interplay with what happens in private?

I took this photo on my roof, when our neighborhood was burning during the uprising in the ‘90s. There's something about fire and rejuvenation that I find interesting, especially with the cyclical fires in California.”

“We lived in an all-lesbian apartment building in Koreatown. Casa de Estrogen. There were two units in the building out of eight that weren't dykes, and it was the best. This is Jenny Shimizu. We called her Chicken. Chicken went out with Madonna and Angelina Jolie while she lived in the apartment above me. She became a Calvin Klein model. When she got put in jail for a week because she didn't pay her parking tickets, all of us at Casa de Estrogen wrote all over her bedroom in marker as if it was a prison cell. There’s a lot I miss about that period.

We repaired our motorcycles in the driveway, complained about girlfriends we were dating, went in and out of each other's apartments at will and shared things really liberally, cooked meals together. We were just being young, queer lesbians—there was that sense of youth and collectivity. At that time, you could live and be poor in LA. I made $8 an hour, and I could afford a $500 a month one-bedroom apartment. LA is no longer the city that’s represented in this show, but it's still a living, breathing, evolving place, just as queer culture is always evolving.”

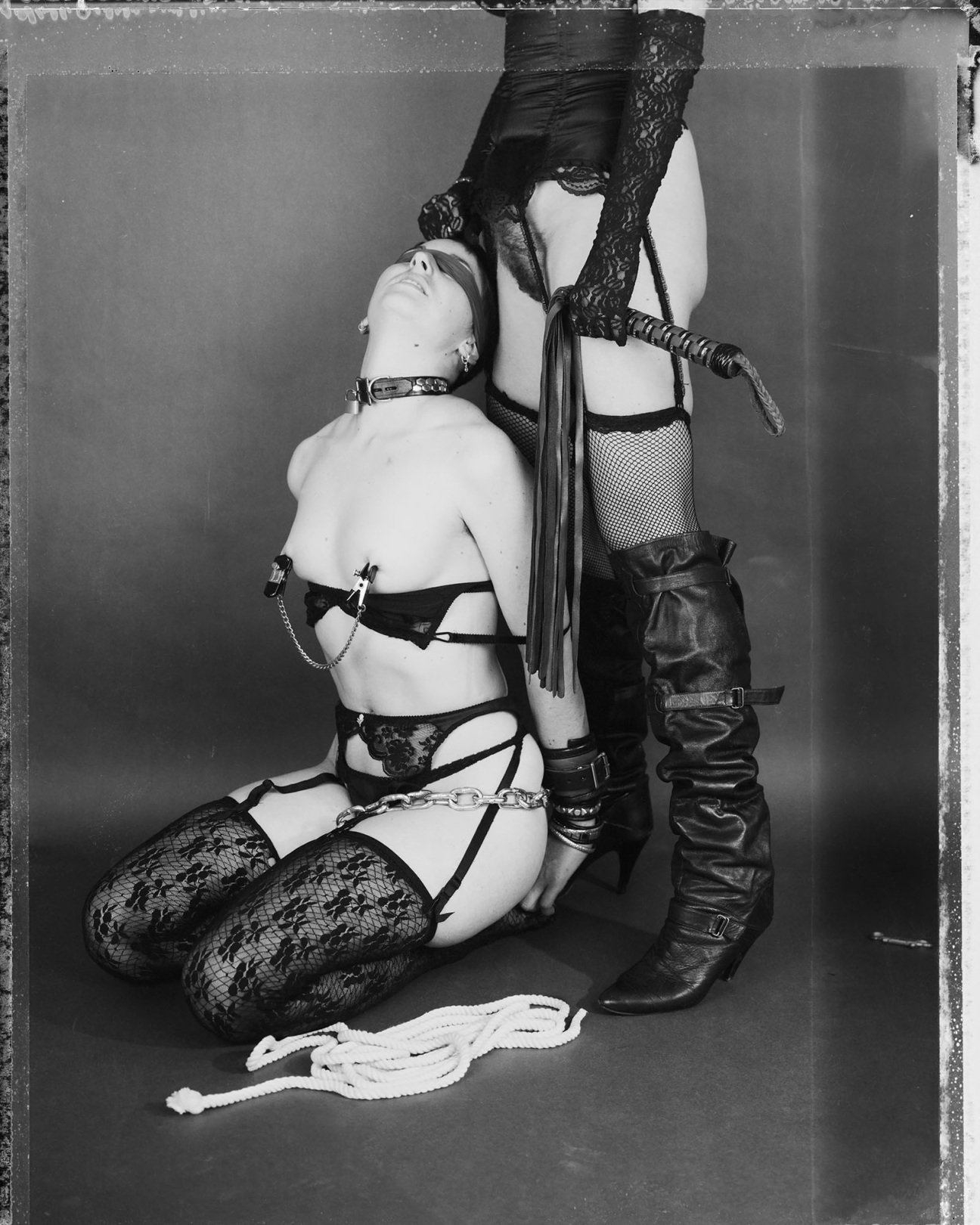

“Pam and I did this. I was trying to make sexy, erotic photographs, but those images never were released anywhere in the art world. They were only in my private archive. When we broke up in 1993, I made Self Portrait Cutting on My Back [Self-Portrait/Cutting contact sheet, 2003]. I had this dream of a domestic life with her, but relationships as a young adult, they come and go. That's definitely represented on these walls.

I've had five significant relationships in my life, and the last one was 21 years with my wife Julie—we've since divorced. Raising a kid with Julie was one of the most incredible experiences of my life, and now that I’m not teaching anymore and the divorce is almost finalized after two years, I’m about ready to [process] it. I'm going off to Norway on Sunday to spend 20 days in the mountains by myself, making photographs of blue mountains under the Northern lights. When I finish a show or I have a breakup, I do something really cathartic—I put myself in an environment that I haven't been in to figure out how to work through feelings. It helps me meditate, and I make images.”