When tuberculosis—or consumption, as it was then named—ravaged 18th and 19th century Europe, it was artists, poets, and writers who crafted outlandish portrayals of the terrible illness in a feverish frenzy to make its fatal effects easier to grasp. While the disease exterminated the masses, causing bouts of bloody hacking fits, debilitating pain in the lungs, and endless days of exhaustion, visual artists used their tools to wash away the sorrow, depicting the angst of the consumptive as if it were nothing short of beautiful. Thus, a period of glamorizing the dead (or soon-to-be) was born.

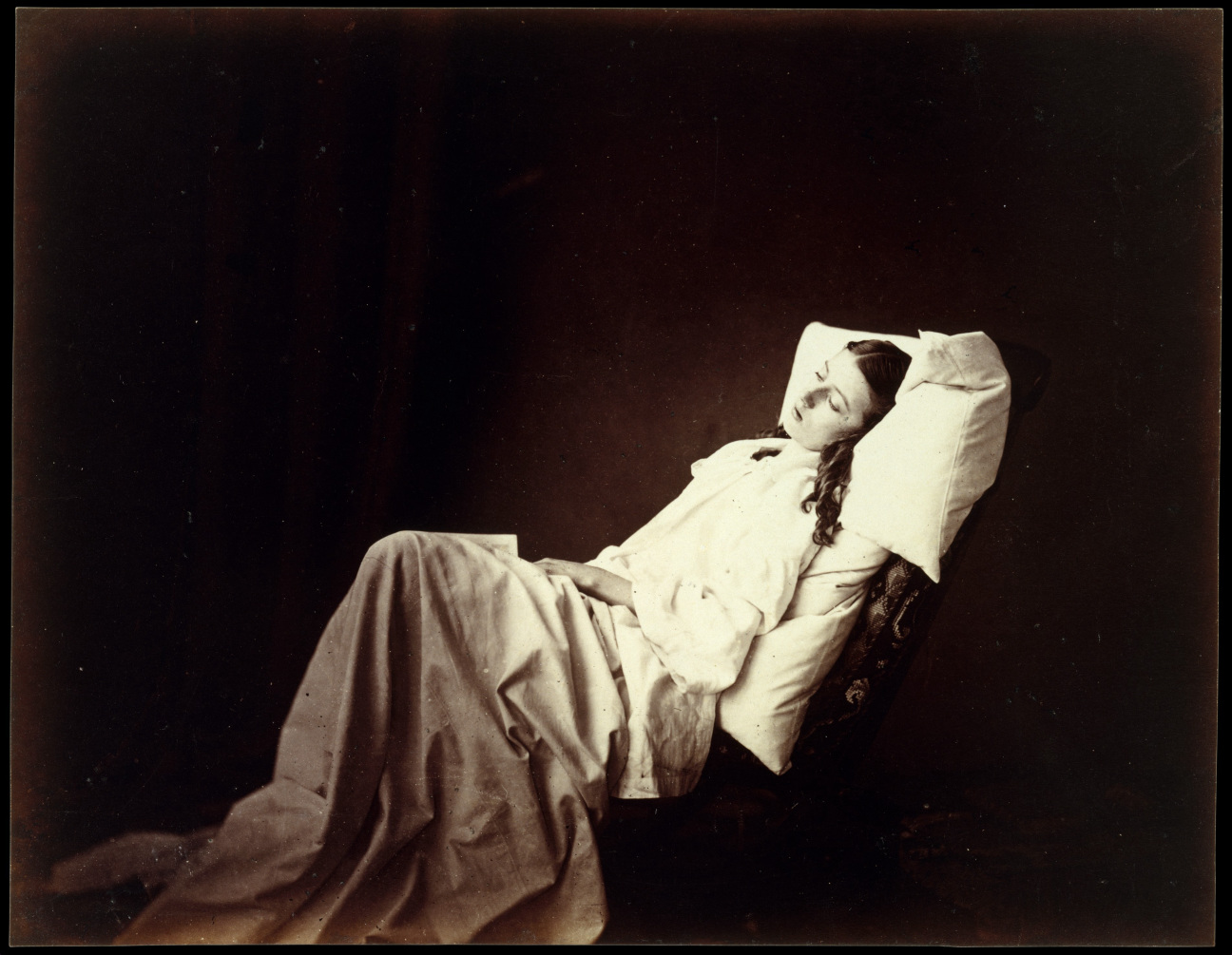

Just look at Henry Peach Robinson's photographs from the era. In She Never Told Her Love, 1857, a young girl lies still and peaceful. Gone are any traces of the grotesque, or the emotional turmoil that likely filled sick rooms to the brim. How lovely to picture someone near and dear drifting pleasantly into death, particularly at a time when medical advancement (or the lack thereof) rendered the outcome a near inevitabiltity. In the opera La traviata by Giuseppe Verdi, 1853, tuberculosis is a disease reserved for romantics and bohemians. It allows the central character, Violetta, to briefly open her heart to her lover before she tragically falls dead at his feet, just as beautiful as before, only paler.

It’s clear why artists would refrain from memorializing the agonized state of their loved ones in favor of a more flattering representation. Unfortunately, the instinct complicated matters significantly. That the emaciating and pallor-inducing effects of tuberculosis were considered attractive in the Victorian era—even desirable—undermined the lethal nature of the disease.

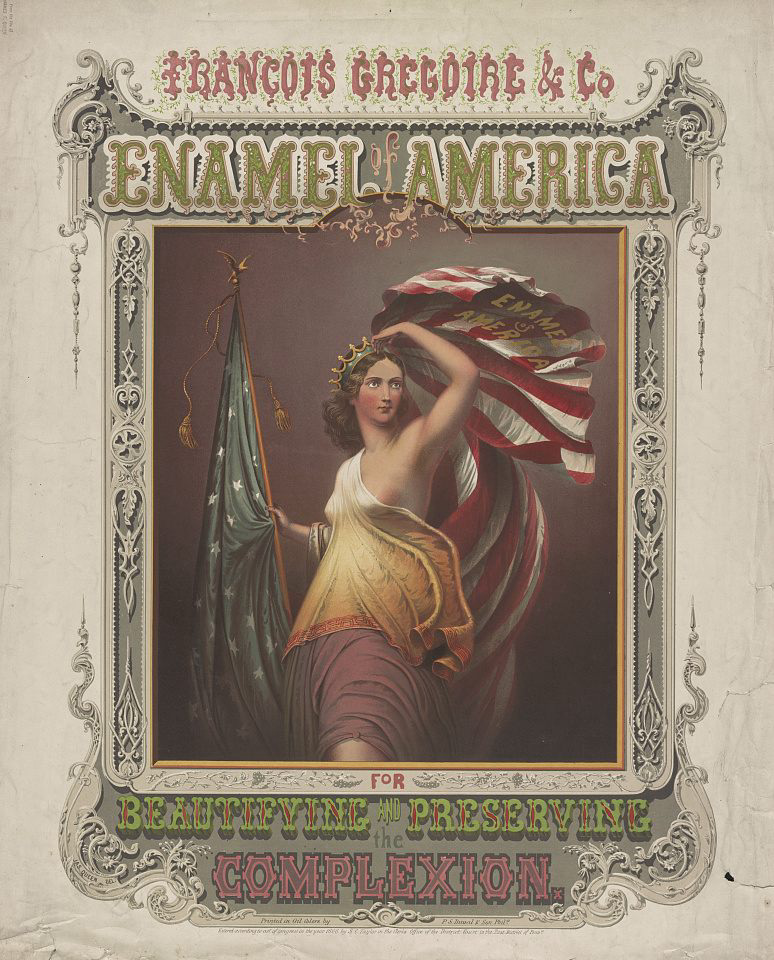

By the mid to late 19th century, the whitening effects of tuberculosis were so coveted that women began swallowing arsenic wafers (falsely advertised to be “absolutely harmless”), washing with ammonia, and covering their bodies with white paints and toxic enamels to aid in lightening their complexion. François Gregoire & Co advertisements selling “Enamel for America” in 1866 boasted a crowned goddess flaunting rosy cheeks and a pale arm, lightened by their poisonous product. Even Charlotte Brontë fell subject to the peculiar mentality, attesting infamously, “consumption, I am aware, is a flattering malady.”

While an aura of melancholy and grief certainly prevails in portraits of the era, there was an undeniable romanticization of disease-afflicted women in particular, even as their bodies crumbled in the throes of death. Let us examine Beata Beatrix dated circa 1864 to 1870, a portrait by the Pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti of his consumptive wife. Here, tuberculosis appears more like an offering than an affliction, a gift bestowed upon the divine. Employing a color scheme of earthly hues that mimic the François Gregoire advertisement, Rossetti depicts his spouse with a celestial face, glowing in its pallidness. It begs the question, which came first, her innate pulchritude—drawing inspiration from the medieval sonnets of Dante Alighieri—or the beguiling effects of the horrible disease?

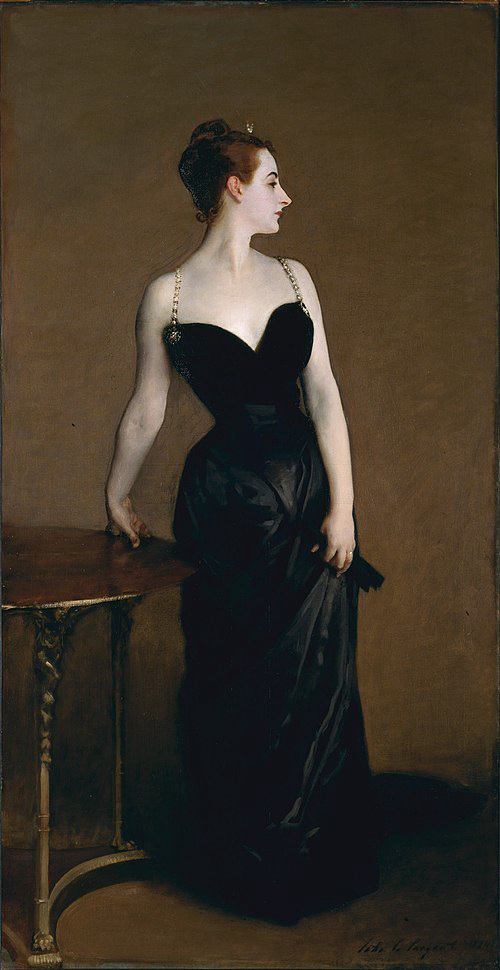

One of John Singer Sargent’s most notable works, Madame X from 1884, captures the inanity of this historical moment head-on. Pictured is French socialite Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau in a waist-constricting black dress, her ghostly white skin luminescent in comparison. It should come as no surprise that such a fair complexion was not blessed upon her at birth; Madame Gautreau routinely coated her face and body with enamel and stood statue-still to achieve the effect of near-translucency, lest the paint crack. Though Le Gaulois, a French newspaper, once deemed her “goddess of the night, all golden powder,” not everyone reacted so favorably. The painting was derided at the Paris Salon of 1884 for showing the right strap of the American-born socialite’s gown falling seductively off her shoulder. Sargent, ridiculed, succumbed and eventually repainted the masterpiece to right what was viewed as wrong.

Reflecting on this bizarre moment in history today, it’s obvious that Victorian society had bigger fish to fry than the state of Gautreau’s shoulder strap. It would be almost 60 years before the cure for tuberculosis was discovered and a long battle ahead to counter the archaic beauty standards by which artists were so enamored. Western society had better get to work.

in your life?

in your life?