Breakout painter Oscar yi Hou is having a moment and taking it all in. Born in Liverpool, England in 1998, Hou moved to New York City in 2017 for an undergraduate degree at Columbia University, landing in the city he always knew he would live and work in one day. Today, he was awarded the third annual UOVO prize, which includes a cash prize of $25,000, a solo exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum to open later this year, and an art installation on the facade of UOVO's Bushwick location. Cultured spoke to the budding painter about representation in the art world, the painters who inspire him and his hopes for his first solo museum show.

Molly Wilcox: Congratulations on being awarded the UOVO Prize! How does it feel to have your hard work be recognized by the committee at Brooklyn Museum?

Oscar yi Hou: It feels awesome. I feel so blessed to be presenting a show at the museum, and I’m grateful to the committee for awarding the prize to me and for giving me such a wonderful opportunity. It’s so great.

MW: Do you have an idea of what you’ll create for the 50-by-50-foot public art installation?

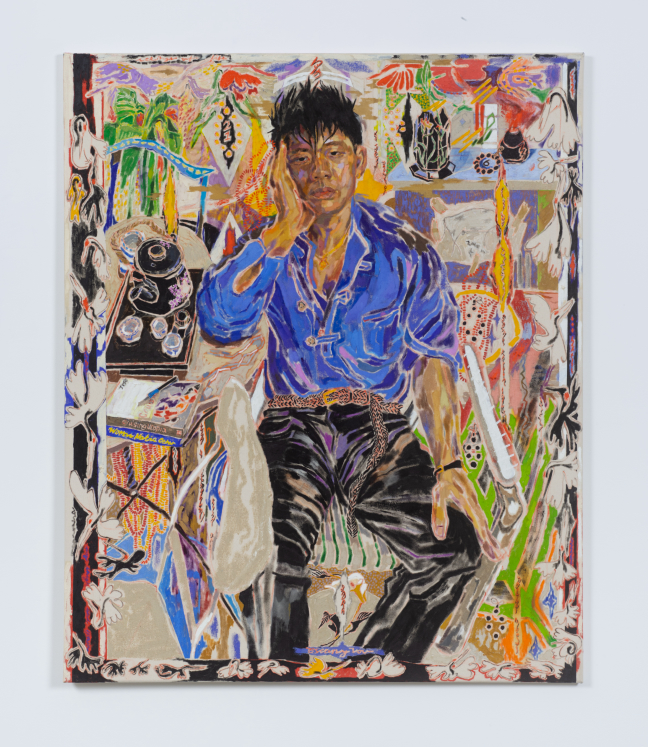

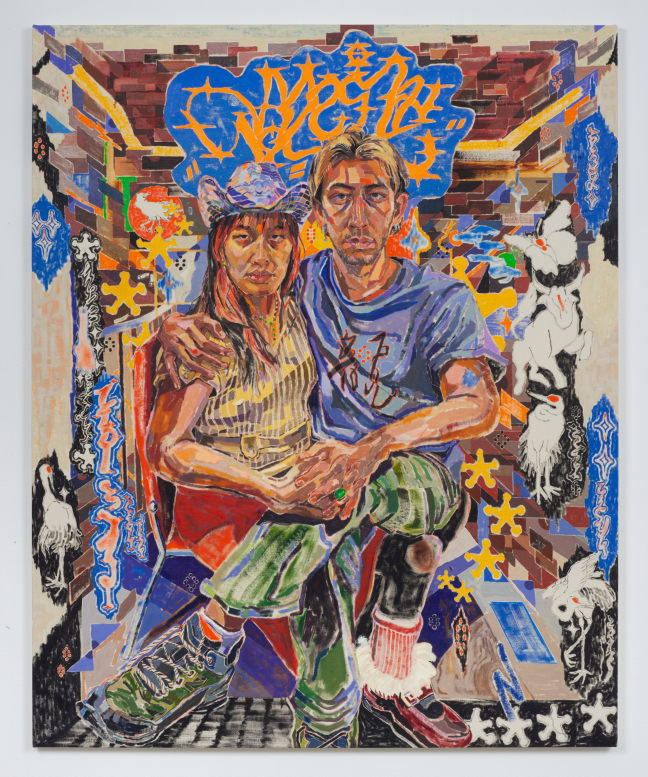

OYH: In my proposal, I drafted up a design using a past painting of mine, birds of a feather flock together, aka: A New Family Portrait, incorporating new graffiti elements and symbols. It’s always been one of my favorite works, so I’m looking forward to revamping it.

MW: What was the inspiration for your latest body of work, “A sky-licker relation?”

OYH: I drew from an eclectic array of sources. “A sky-licker relation” felt like a natural development in my practice, but certainly there were things that occurred during the making of the show that I can point to as direct inspiration—I’m thinking of that Alice Neel show at the Met last year. My painting A crane and two sea-goats walk into a bar, aka: Summertime Cosmogony on Old Broadway (2021) was compositionally based off Neel’s painting Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian (1978). It’s the one of the gay couple with the fruit bowl on the table next to them. The guy on the left is a lot more butch, with his unbuttoned red flannel and exposed chest hair.

In my piece, I wanted to follow a similar dynamic, but with a lesbian couple. Additionally, the setting of the painting is the apartment from when we lived back in Harlem last year, so I kind of wanted to do an ode to that place, since it was our very first apartment in New York. The number at the top of the painting (556) was our building number, and Old Broadway was our street. You can actually see into our respective rooms within the painting. So I suppose, amongst other things, that I was inspired by all these things happening in my life at the time.

MW: What can you tell us about your new work for the Brooklyn Museum?

OYH: It’s going to be a combination of my figurative work and my poem-picture practice. In addition, I’m going to incorporate depictions of artifacts from the Brooklyn Museum’s Asian Art collection. I already utilize archival materials a lot—a lot of the cranes or other symbols are referenced from artworks or objects within Asian Art collections in the West, usually images I find online. I’m interested in how Orientalism continues to haunt Western ways of knowing. So being able to work closely with the museum’s collection is going to be great!

MW: Your paintings have so much depth and complexity of image—how do you use symbols and patterns to enhance your work?

OYH: Everything signifies something but, of course, symbols are the most transparent about it. Symbols can have multiple, sometimes opposing meanings, like the five-pointed star, which can signify socialism if it’s painted red, or a state of the United States on the star-spangled banner. I try and weave a web of signifiers within each painting—there’s continuity between different paintings if you look close enough. There’s a shared lexicon. It’s kind of just like writing with words, but instead you draw from a symbolic language system instead. Things like grammar and syntax still apply.

MW: When did you realize you were going to pursue art as a profession?

OYH: I was pretty existentialist as a teenager. It sounds a little corny to say now, but I realized that I only had one short life, that the universe was indifferent to whether I succeed, live or die, etcetera, and that I had to somehow take life into my own hands and mold it according to my own desires and dreams. I knew that there were actionable steps I could take towards doing what I wanted to do: I wanted to end up in New York and I wanted to be an artist. I was confident enough in my own capabilities, and I felt like I genuinely had something new to offer. I was always very clear headed and ambitious about it all.

Despite my family really discouraging me to pursue art as a career, I knew that fundamentally I wouldn’t be satisfied in life if I wasn’t aligning my career with my art making, and that, at the very least, I owed it to myself to give it an honest attempt.

MW: Which painters have recently influenced or inspired your own work?

OYH: In terms of painters, I’m inspired a lot by Martin Wong, Alice Neel and Kerry James Marshall. They’re timeless painters. Some others I’ve been looking at recently have been Odilon Redon and Marsden Hartley.

Otherwise, recently I’ve been looking at a lot of Japanese homoerotic artists of the late 20th century, such as Tamotsu Yato or Sadao Hasegawa. In particular, I’ve been incorporating a lot of yin-yang symbols in reference to Hasegawa.

MW: How has the topic of representation and identity influenced your life and your art?

OYH: I think about race all the time. It can be a little cumbersome at times, but it’s always there. I think a lot about the politics and meaning of “yellowness” and its relation to the larger American racial program.

I think that being queer, and I’m sure that this is something others might relate to, is what compelled me to realized that another life was possible. I think that’s the beauty of queerness: it veers you off the straight path; you don’t have to follow any blueprint. You can make shit up and choose your own way of life.

in your life?

in your life?