Early Sunday mornings, when the light is at its most lyrical, Sam Parker and his wife Madeline Hollander do yoga. Their 1924 Tudor home—rented, not owned, containing five rooms—sits at the edge of Griffith Park in Los Angeles. They do tree poses and downward facing dogs in a room filled with art, not because they are collectors, but because Parker runs a gallery from their house. They’ll be in the company of Gladys Nilsson, Peter Bradley or Roy De Forest, depending on the exhibition, and Ringo, their standard poodle the color of apricots, will come in and cock his head in curiosity.

Started in 2017, Parker Gallery has since mounted an ambitious, intergenerational program focused on early-career artists as well as those in their eighties and nineties. “I realized soon enough that it would be a really important angle of the gallery, to reintroduce a lot of artists that’d been forgotten,” Parker says. One recent exhibition was a restaging of “The De Luxe Show,” arguably the first racially integrated art exhibition in the US in 1971. Parker, along with New York-based Karma Gallery, included pieces that appeared inthe original show, as well as newer work by the artists.

With a combination of intentions related to both the market and museum, Parker belongs to a long line of domestic spaces functioning as art spaces. New York’s storied apartment galleries aside, there is the less well-known history of such spaces in California. Bill Copley ran a gallery in Beverly Hills in the 1940s where Man Ray had his first California show, and Candy Store Gallery, a former candy store turned residence and then gallery by Adeliza McHugh, gave Jim Nutt his first show. Parker himself also has a familial connection to the history of such homespun tendencies: His grandmother, fiber artist Gertrud Parker, started the San Francisco Museum of Craft and Folk Art in 1982, which she initially ran out of her home.

Belying these intimate settings, Parker Gallery also seeks to provide a wider platform for Northern California artists and their aesthetics; it’s a region which gave birth to the wildly influential Funk and Nut Art movements, whose colorful tendrils would touch fine art and pop culture alike. “I find that I often have to temper my own personal taste,” Parker says. “I’m definitely attracted to the eccentric and the wily. I get really excited about something that confounds me and pushes the boundaries of good taste.

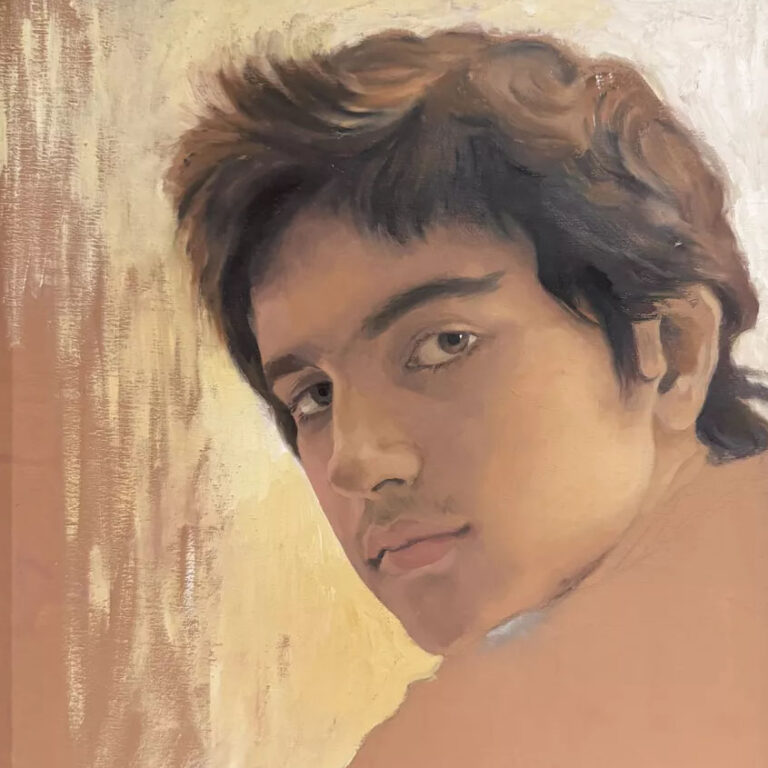

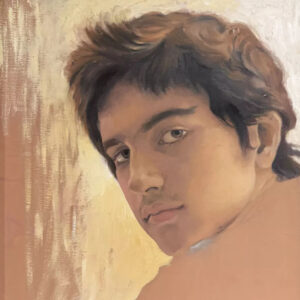

Currently, the early work of Joan Brown, the Bay Area figurative painter known for people and animals rendered in fanciful color and everyday settings, often domestic ones, is being shown by Parker. Brown, who tragically died in1990 alongside her two assistants while installing a ceiling mosaic at the Eternal Heritage Museum in Puttaparthi, India, was a crucial figure of the movement that struck out against the dominance of abstract expressionism. A goal of Parker Gallery is to give Californian artists their due, but also to put them in conversation with the outside. “I think Northern California has always had this really regionally focused mentality and it’s hard to get beyond that,” Parker says. Sometimes, to understand home, you have to leave it, then come back.

in your life?

in your life?