Andre D. Wagner sits on a stoop outside his Bushwick apartment, watching the neighborhood unfold at dusk. A girl, no older than six, twirls in her tutu in front of a bench. Four other kids are in motion—laughing, dancing and playing around. Unhurried, Wagner adjusts the settings on his 28mm Leica M6, an appendage he never leaves home without. He tweaks the shutter speed and the F-Stop, puts the camera to his eye and clicks.

In the resulting black-and-white long-exposure photograph, the girl’s tutu becomes a cloudy blur. A boy is caught mid-jump. One girl’s body is a complete haze, like that of a ghost’s.

Wagner is a sought-after photographer. He regularly contributes to “The Look,” a New York Times column. His Instagram account has amassed upwards of 97,000 followers—including Erykah Badu, who regularly comments on images he shares. Lifestyle brands like Madewell and Hennessy tap him for campaigns. Yet Wagner prefers shooting regular people in the streets: A barefoot kid playing with a bursting water hydrant; a tattooed woman in the subway writing “Fuck Trump” on a blank sheet of paper; two women wearing hijabs whispering to each other under a bridge. In the midst of commissions photographing the likes of Dua Lipa, Issa Rae and SZA, Wagner remains dedicated to telling narratives about people of color in New York City.

Watching him photograph in the streets is like watching an agile player in a basketball game—no surprise, as he was a scholarship athlete at Iowa’s Buena Vista University with aspirations to play professionally. Wagner averaged 20 points a game in college; his coach at Buena Vista, Brian Van Haaften, remembers his unusual quickness and how “creative” he was with the ball. His former teammate, Brian Fogelman, describes him as the most talented player on the squad. Nonetheless, after his senior year, Wagner did not make the cut for the Iowa Energy (now Wolves), a minor league NBA team. With his pro basketball dreams squandered, he focused instead on his major, social work.

The son of a pastor and a human resources director, Wagner grew up embedded in his community. His mother, Donna Wagner, says he has always been sociable, “He could make friends very easily, because he’s that little jokester that little boys and girls gravitate to because he can get down to their level.”

This relatability was evident when he began volunteering at a juvenile court during his fifth year of college. “All of my colleagues were white but all the kids I was working with were students of color. I had this important role all of a sudden because I was somebody that connected to the kids, because we talked the same language,” Wagner told me.

After graduation, he pursued a master’s degree in social work at New York’s Fordham University, moving to the city in 2011 with only $60 in cash. Student housing provided an apartment at the Wilshire Plaza on 58th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues. “I was living in this fancy place but I was broke as hell,” he says of the time when he amassed IOUs at a dollar-a-slice pizza place and picked up discarded furniture off the street.

Determined to make a living, Wagner quit grad school and worked at e-commerce site, Fab.com. As their in-house photographer, Wagner drew on some rudimentary skills he’d picked up in a college photography class, and when he was later laid off, he decided to freelance and invest in a 35mm Leica camera.

Wary of “manufactured” portrait shoots, he fell in love with street photography. He perused books on photography legends and stayed up until four in the morning to watch YouTube clips about them. With an athlete’s discipline, he trained daily, shooting in the streets.

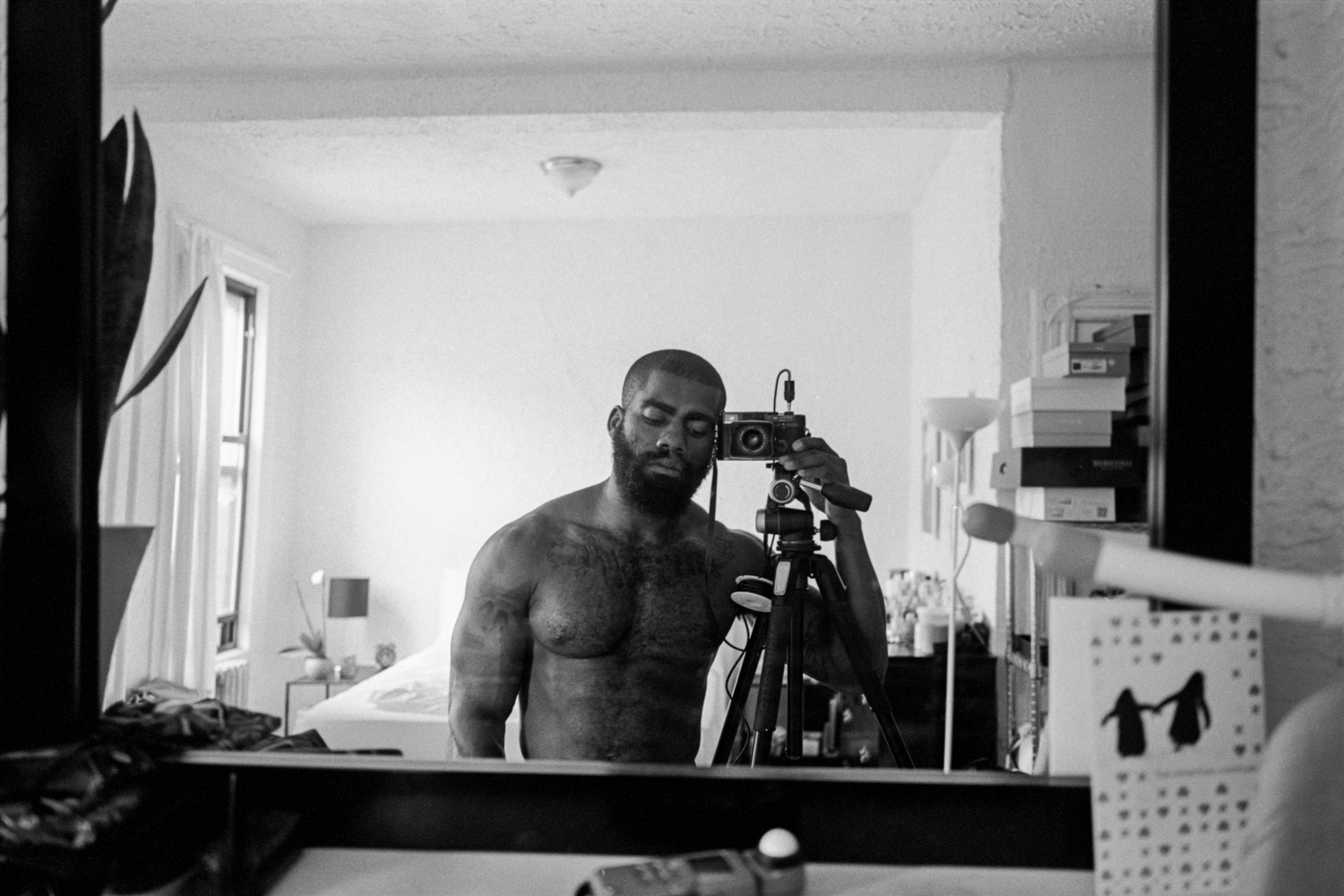

Save for a desk full of contact sheets, a Mac monitor, and a chair, his home workspace remains bare. Across his desk, shelves nearly sag with books of his idols: Irving Penn, Robert Frank, Richard Avedon and Garry Winogrand, whose iconic black-and-white “World’s Fair, New York City” photograph flickers as Wagner’s desktop wallpaper. He even collected three copies of Roy DeCarava’s The Sweet Flypaper of Life—he bought himself an original and a reprint, while the third was a gift from his wife, Lindsay Peoples, the editor-in-chief of Teen Vogue.

Wagner grabs a thick clear book from the bookcase and flips through photos he took in college, shaking his head in embarrassment at what he sees: pictures of a white poodle (his mom’s dog) occupying more than a third of each frame.

Watching her husband graze through his early work, Peoples, who met Wagner in college, recalls how creative he was as a student, even if he hadn’t found his place in photography yet. As part of their early courtship, Wagner wrote her letters, gave her “immaculate” drawings, and helped her with her arts homework.

Wagner told me he’d been so uninterested in his college photography class that it wasn’t until years later, after he’d been living in New York, that he realized how big a mark the course had made on him. In an interview, Bruce Ellingson—the professor of this college class—placed Wagner’s work in the context of such legends as, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand, saying that Wagner’s images share their passion for the moment and the people.

Ellingson is right. Wagner’s aesthetic recalls Winogrand’s slightly intrusive and voyeuristic tendencies. Even the energy feels similar. Both capture fleeting moments—conversations between friends, intimate exchanges between lovers, and people in transit. Like Winogrand’s, Wagner’s photographs also require proximity to the subject—a mere four to eight-foot distance—rendering his process rather invasive. Today, kids around his block know Wagner and pose for a photograph the moment they see him.

The apartment he and his wife share isn’t all work, though Peoples says sometimes it feels that way. “We’ve had arguments about it because he takes his camera everywhere but I think it’s a natural extension of who he is,” she says. She also teases him about how fastidious he is about photos, saying that even she isn’t spared from his criticism when she takes iPhone shots. He’s commented on her “bad cropping” and lack of attention to detail, like not noticing “poles coming out of [her] head.”

He rebuffs this by lauding his utility as a “great Instagram husband,” always offering to take different angles of Peoples’s outfit photos—though his services come with commentary, warranted or not. “He makes names for my outfits like when I put my Fashion Week looks together,” Peoples says.

“She had this all-white outfit on, and I called her a marshmallow,” he replies.

Peoples pokes fun at his choice of clothing too. “God, if it doesn’t have pockets we cannot bring it home. Sometimes it’s gotten a little Indiana Jones with the vests!” she teases. The pockets do serve a utilitarian purpose: they carry rolls of film.

During the summer, Wagner shoots from sun up to sun down, walking five to fifteen miles a day in his favorite places: Brooklyn, Harlem, the Bronx, or busy areas like Canal Street and Union Square. He goes through hundreds of 36-exposure film rolls a month. As colder months start rolling in, the printing process begins in his dark room—his personal cave behind the kitchen—which he built machine by machine. He laboriously sifts through the resulting 16×20 prints, as he compiles his newest book project, New City, Old Blues, to be published in 2020.

His first book, Here For the Ride, published by Creative Future, chronicled the commuter life in New York. All 750 copies sold within the first month. Now, Wagner dedicates his second book to people of color in America. “If you’re a black male, it’s a lot of old blues,” he says.

Traditionally, narratives about people of color were rarely told by members of the communities themselves. But more and more, art institutions are placing stock in the perspectives of photographers like Wagner. Roy DeCarava, the late African American street photographer, had two simultaneous exhibits at David Zwirner’s Chelsea galleries last Fall. In “Down These Mean Streets,” a show that closed in January 2019, Museo del Barrio featured ten Latinx street photographers. Wagner belongs in this canon. His works were commissioned by the Smithsonian Institution for the exhibit “Men of Change,” which is geared for a three-year tour around the US. According to press materials, the show, currently on view at Tacoma, Washington, aims to “amplify decades of Black excellence and activism.”

“I have a point of view and, as a black man in America, having a point of view is innately political,” Wagner told me. “My goal is for my photography to be written in American history,” says Wagner.

in your life?

in your life?