When my father evokes images of Iran, he speaks of gardens—rose bushes, fragile and bloomed. Hossain Sabzian crying and clutching a bushel of pink in Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-Up. The vivid green of Iran’s pastures, the brightness of its fuchsias, the rawness of its blood reds. The early historian Herodotus wrote of Iran’s kings taking a pleasure in gardening, and told of how the Charbagh, a landscaping layout based on the four gardens of Paradise from the Qur’an, came to be. Gardens are an integral part of Iranian lore, of Iran itself.

The garden is also a motif that repeats in the works of Iranian artist and filmmaker Shirin Neshat. In her film Women Without Men (2009)—based on the novel of the same name by leading Iranian renegade Shahrnush Parsipur—the garden is where the women of the film return for safety. “Women Without Men is about an orchard where women run to take refuge, and it becomes a sanctuary,” Neshat tells me as we sit in her Bushwick studio. “It is about a garden that people who are afraid in the world run to; a place where you feel free to be naked, to be yourself.” Much of the film, and the story it draws from, is predicated on the garden, both literally and metaphorically. The garden motif is the beating heart of the film.

I met with Neshat on a frigid Sunday morning in mid-January. She had invited me to her home and studio, and as soon as I entered the space I was astounded by the beauty around me. It was a sincere reprieve in a harsh city like New York, with high ceilings, light wood interiors, walls cascading with books in English and Farsi and Persian carpets covering a sleek cement floor. Along the back of the glorious main room there were plants that lined the wide windows, small emblems of comfort: trees of spirulina green and flowers standing tall in towering glass vases. Her partner and frequent collaborator Shoja Azari (who co-directed Women Without Men and many of her other films, and also stars in Neshat’s video Turbulent) sat in a black leather chaise reading Leonard Cohen’s posthumous book of poetry, The Flame, while taking wispy pulls of his Juul. Both of them were curious about my life in a way that felt comforting, and I was eager to tell them. In a way, I felt like I had returned home.

We walked downstairs to Neshat’s light-filled studio, encountering human-sized prints of stills from Neshat’s recent film Looking for Oum Kulthum. Eventually, we sat down and began our conversation over coffee (for me) and a bowl of raisins and prunes for us to share.

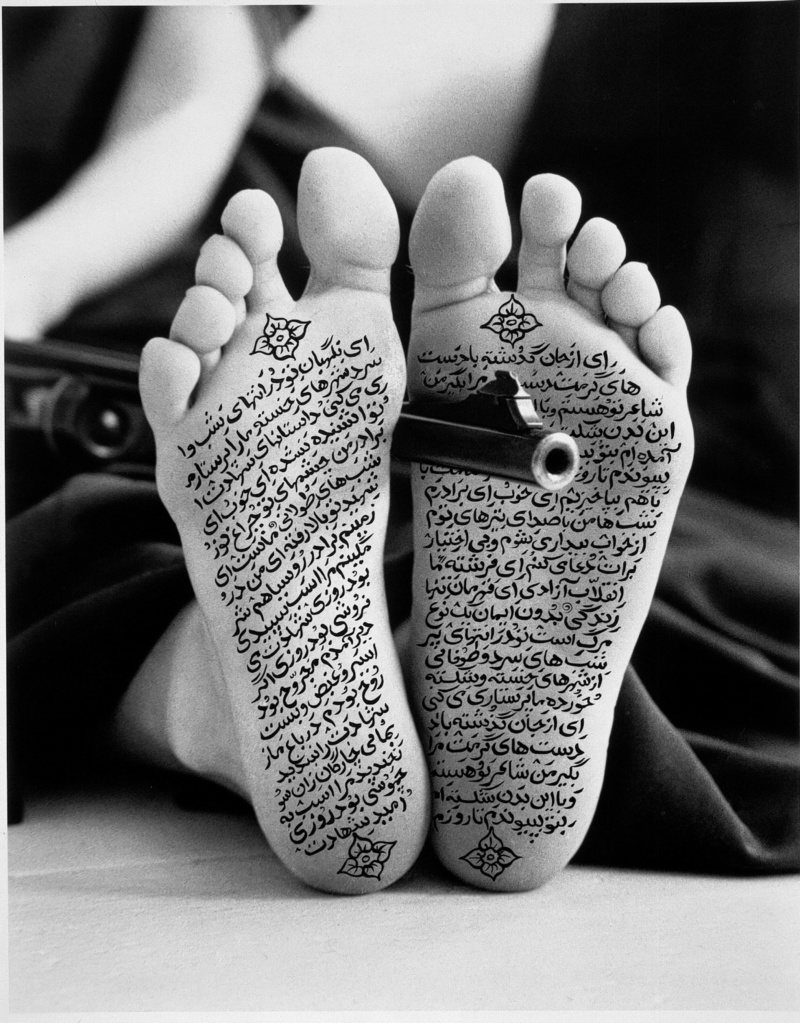

Over the years, I’ve consistently followed Neshat’s work. The images in her photographic series Women of Allah (1993–97) are seared into my brain because they were an important first for me: In these pieces I saw, for the first time, a (Muslim) artist take photos of women cloaked in chador without fetishizing them. And these women felt powerful, equipped with agency—wielding handguns, their stances were strong-willed and their look was infectious. To this day, the images are iconic, a synecdoche for the sprawling impact of Neshat’s work. Part of this legacy stands because Women of Allah is a vivid juxtaposition to the existing images of Muslim women, which the Western world has little curiosity for. As the scholar Hamid Dabashi writes in Shirin Neshat: The Last Word, “She demystifies the act of veiling via an orchestration of the face, simultaneous with choreography of the body.”

The images are inscribed with the Persian poetry of the late iconoclast Forough Farrokhzad, whose work was a profound inspiration for Neshat. “Had it not been for her words, I would not have made the images,” she tells me. One piece reads: “Weary of divine asceticism, in the middle of the night in Satan’s bed / I’d seek refuge in the slopes of a fresh sin.” It’s this interlacing of the divine with its opposition which hit (and still hits) as such a powerful exploration of oneself—especially coming from a Muslim woman, herself. This entire series questions what it means to be subjugated, while coyly asking: Who is really doing the subjugating?

There is no monolithic experience of being a Muslim woman. But, to me, Neshat’s work on Muslim womanhood is a challenge to the powers that have compressed us into contradictions. “Women were basically seen as objects and a battlefield for men’s ideology. What’s really interesting is that it’s so far removed from reality,” she says astutely. “If I have to specifically talk about Iranian culture, not only in my mother’s generation, but also in my own generation and even today, women are the most unruly, rebellious, confrontational beings in the entire society.”

In a 2010 TED Talk, Neshat surmised, “The women of Iran, historically, seem to embody its political transformations. So, in a way, by studying women you can read the structure and the ideology of the country.” So much of her work questions the interiority of Muslim women in a way never before deemed possible—and, as such, her output has often been misunderstood. In accordance with the relative lack of understanding around Islam, many early critics couldn’t quite fathom the message of her work. Writing in The New Republic in 2001, Jed Perl criticized Neshat for not having a viewpoint. “All that a viewer gets,” he wrote, “is a generalized mood, a kind of artsier MTV.” Perl’s incomprehension perfectly illustrates the risks that come with non-Muslims writing about Muslims: the tendency of playing too hard into the Orientalist messaging and depicting us incorrectly, muddying our placement or siding us with fundamentalism.

Neshat understands that conflict, though, and plays into it; she taunts the viewer into self-reflexivity. In The Shadow Under the Web (1997), she places four vignettes of a woman in a chador running through Istanbul, almost chanting, breathing with a beat. It’s the way Neshat positions the body as juxtaposed against its environment that’s so powerful. These women (four, or one?) existing, rapturously. Is she tormented by sadness, by anxiety? We may never know, but she’s beating with life, with a pulse that feels alive. In Rapture (1999), a group of women in a wide frame is contrasted with a group of men in an adjacent frame. While the men fight in their frame, in the other the band of women stands in unison, a throat chant drawing them solace. At times we hear Qu’ranic verses or the muezzin call to prayer spread through the work, like a compass.

While we talk, we discuss the vast riches of Islam’s legacy and its sincere impact on our lives. You can tell that her upbringing—being both Iranian and Muslim—has played an important role in her life, let alone her art, and how it’s determined the pastiche of her being. It’s incredibly compelling to watch such a resilient artist rely and lean on spirituality as she does. It’s humbling, and it makes me feel closer to her. When I ask who inspires her, she speaks of Tarkovsky, but also of the women of Iran, including Farrokhzad, Parsipur and others she’s met along the way; of Rumi, her homeland and the orchards of her youth. She speaks of the thrill of “living on the border of immigrants,” about her life in New York City, her adopted home, and how she exists in a state of constant metamorphosis. We discuss the loss of color in Iranian society, of the palpable pallidness post-revolution and the austerity that has soaked into the fabric of Iran’s collective imagination. She houses all of this; she’s multiplicitous. The beauty of Neshat and her work is that she’s always in conversation with herself. Nothing is ever dull. Like a true Iranian garden, she’s a sanctuary. But she’s also a rose: pushing boundaries, simultaneously beautiful and caustic and, in special moments, opulently in bloom.

The artist’s first major West Coast survey, “Shirin Neshat: I Will Greet the Sun Again,” will open in October 2019 at The Broad.

in your life?

in your life?