As Malcolm X once said, “Every defeat, every heartbreak, every loss, contains its own seed, its own lesson on how to improve your performance the next time.” Like so many artists, David Benjamin Sherry owes some of his earliest (and latest) breakthroughs to losses, both personal and political. Though he is now a self-possessed (and artfully-tattooed) young master of his trade, a decade ago the New York-born, Los Angeles-based photographer was a self-described “late-blooming, coming-of-age 26-year-old” just finishing up his MFA at Yale when a close friend of his passed away.

“The only thing I could think to do was to go travel around the Western states by myself,” recalls Sherry, now 36, in a moment of soft-spoken reflection. “I brought my camera and ended up taking a lot of landscape pictures, connecting to the outdoors, and just coping with life and death and the passing of somebody.”

Though he’d been flying to L.A. and Las Vegas the year prior—saving all his money to rent a car and document Death Valley, Yosemite National Park and various natural wonders around the Southwest— Sherry was just “dipping my feet in landscape work then,” he says, adding, “I was really interested in breaking down boundaries in what my interests were. I wanted to build an experience with photographs and photographic installation so I was shooting people and places and abstract images.”

It was during this time that Sherry—with free reign over multiple analog labs at Yale; while his classmates were busy with their new digital files— developed a repertoire of hand-made dark room techniques that have become his signature. By filtering his images through 150 varying degrees, respectively, of cyan, magenta and yellow Sherry learned how to manipulate his early images—many of which included landscapes, as well as the artist and a friend covered in body paint that often color- matched the environments he was documenting—with floods of super-saturated colors.

“Around 2006 was when I had first come out of the closet so color was a way for me to add another layer, it was a way to speak about something I couldn’t really vocalize myself,” says Sherry, citing the mystically coded black and white prints of the closeted landscape photographer and Aperture founder Minor White as an early inspiration. These newfound color techniques allowed for what Sherry calls “a more emotional experience.”

A decade after his friend’s death, Sherry experienced another profound sense of loss (for words, at first, and later for the potential threat of his own civil rights) in the wake of the 2016 presidential election. Like many artists, Sherry immediately hit the streets—in his case, with a large format 8×10 camera—photographing rallies and protests. Yet while the political climate in the country was drawing him toward the community of resistance, his artwork was drawing him back inside the darkroom to one of the medium’s earliest forms: the photogram.

“The photograms were born out of a need to isolate myself and be alone with myself and understand internally what was left inside creatively that I could use to make sense of the outside world,” says Sherry, who has spent the bulk of the past six months shuttered inside a Lincoln Heights photo lab (with occasional smoke breaks, and a few hours at night to see his dog) imprinting performative, if highly focused, gestures onto light-exposed photosensitive paper. “I literally shut a door behind me and shut myself off into isolation, into darkness, and really let intuition take hold.”

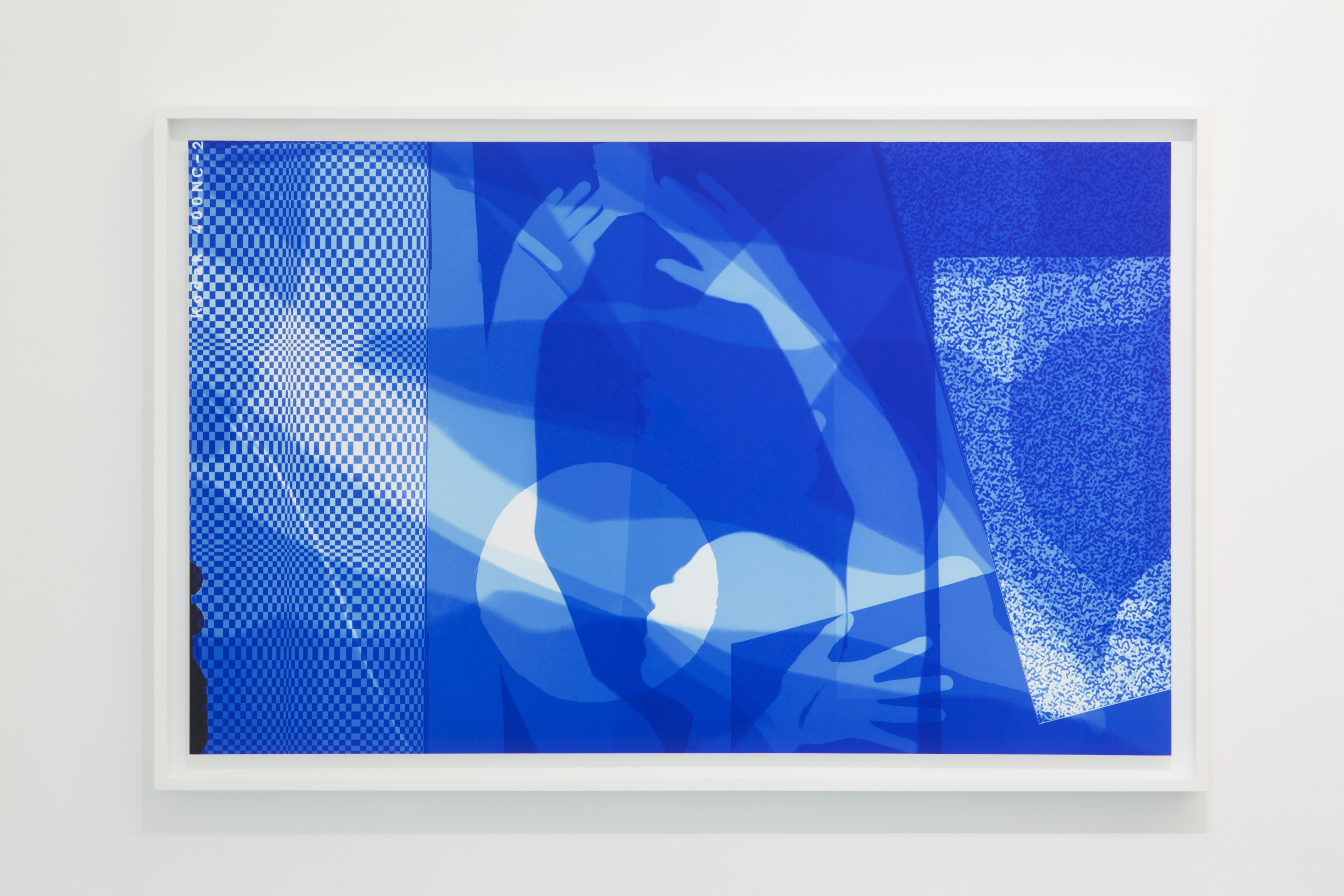

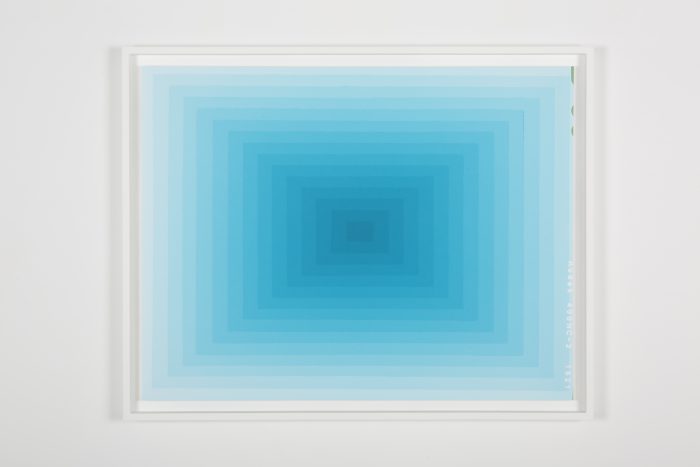

The result of that intuition is “Pink Genesis,” open through July 28 at Salon 94’s gallery on the Bowery, which will feature 12 richly colored (and highly textured) new photograms in two types: a series of stacked geometric circles and rectangles whose radiant glow and hard-edge minimalism is interrupted sparingly by the artist’s hands (in certain cases) or the Kodak labels burned into each border; and various images of Sherry’s body—and his dog’s—interlaced with moire patterns and rectangular frames. In one epic figurative piece, spanning the entirety of the artist’s Pepto-tinted, magenta-haloed silhouette, is a recent NASA photograph of an expedition to Mars whose dunes appear to vibrate with white hot atomization. These painterly echoes of figuration, graffiti and geometric abstraction are attempts—very calculated stabs in the dark, if you will—for the artist to create a “portal” from the outside world that teases at representation the way a shadow might haunt the strobe lit floors of a dance club: light and heat and motion captured for one bright, beautiful moment.

“A lot of them are born from landscapes. That feeling, that connection I feel to natural places and these western landscapes is behind a lot of the photograms. How do you explain the feeling when you’re alone in the desert watching the sunrise? That’s where it begins,” says Sherry, who first exhibited monochrome photograms depicting Oregon’s Blue Basin Valley, Utah’s Moab and California’s Zabrisky Point among other landmarks in “Astral Desert,” his 2012 debut at Salon 94.

“I think it was a way to find beauty, spirituality and something poetic when he couldn’t find that anymore in the outside world,” says Salon 94 founder Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn, who debuted four of the new works to great interest at the Frieze Art Fair in May. “Here is somebody who is constantly seeking the great American grand landscape and all of a sudden he wasn’t finding that so it makes sense that he found that in the dark room.”

While artists as disparate as Iñaki Bonillas, Thomas Struth and Mariah Robertson are looking to the photogram as a time-tested avenue for exploring new visual languages—be it in a nod to Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Man Ray, or simply to break down art historical conventions—Sherry’s reflective (and reflexive) experiments feel like a breath of fresh, neo-Turrellian air within the medium.

“I think that a lot of my work from the beginning has been about this otherworldly, mystical, alchemical, analog process. This, to me, was digging deeper in that process and finding my own deep connections to mysticism, queerness, the landscape, environmental concerns, my body, our bodies, human connection to nature, human connection to each other. And that’s what is in a lot of them: there are remnants and different types of perceptual patterns that create a sense of depth,” explains Sherry. “It goes along with this political era in which we’re living. I’m trying to create a space as a portal to fall into. Not like an escape, it’s just more telling of the last few months and what this feels like in my mind, this dizzying, bottomless vortex, like a loss of gravity, what space might feel like. I kind of reunited myself with what it was that led me to begin taking pictures in the first place.”

Images courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York.

in your life?

in your life?