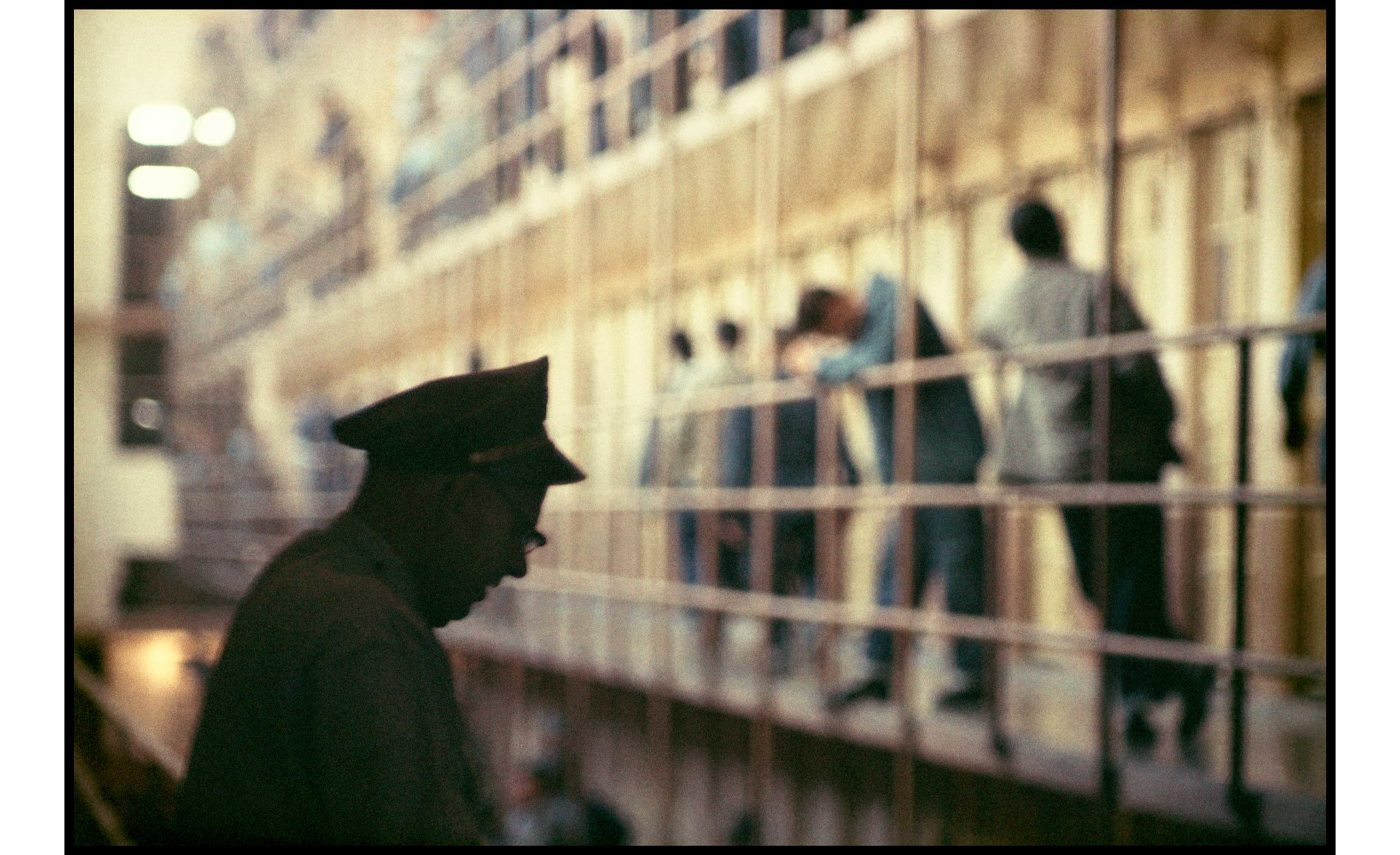

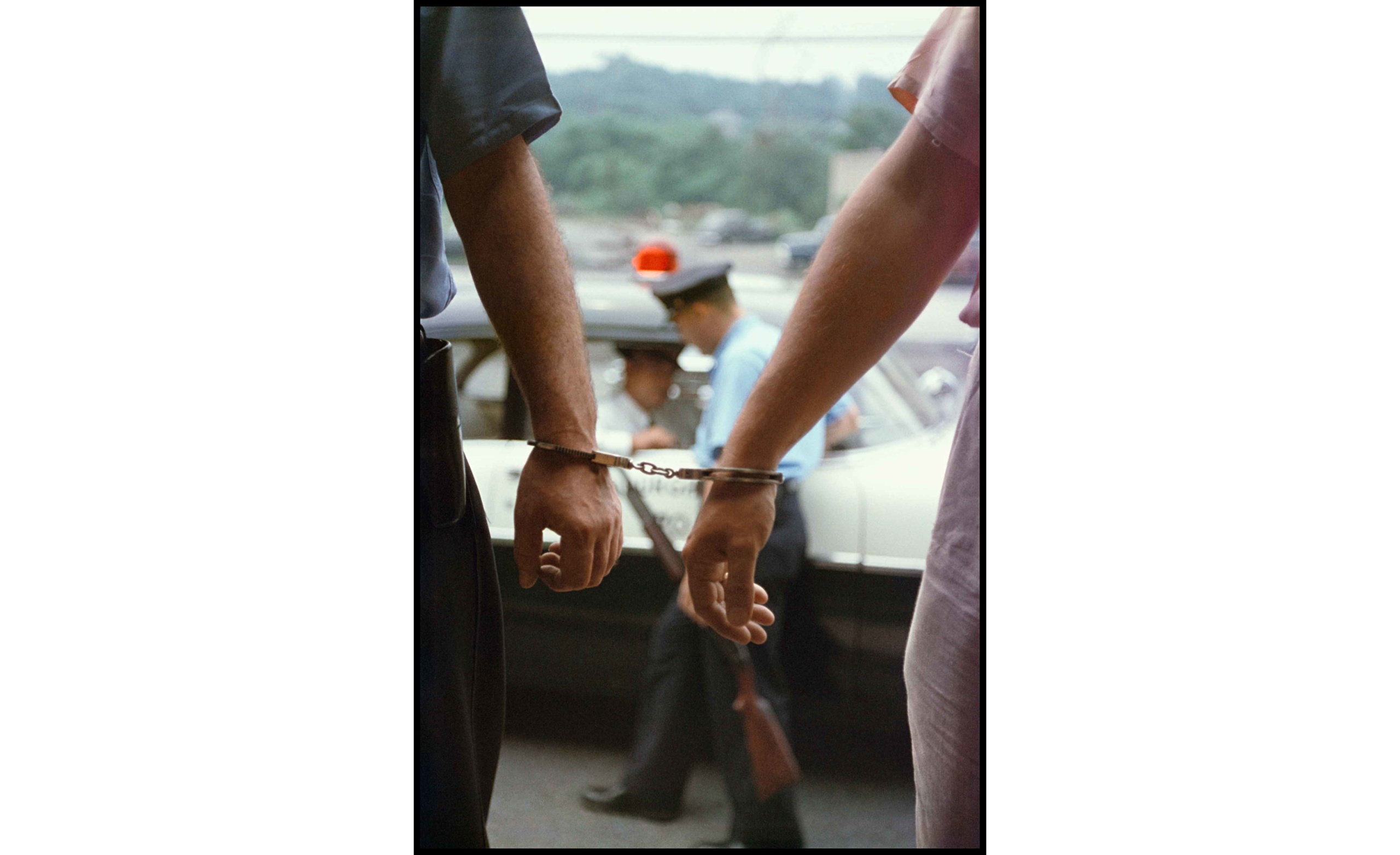

“Unfortunately, the story that Gordon Parks captured for Life Magazine six decades ago—pictures of Black people being terrorized by the police, stalked, questioned, handcuffed—feels terrifyingly contemporary,” says Museum of Modern Art curator Sarah Meister, who organized a collection of photos from Parks’s 1957 series, “The Atmosphere of Crime,” to anchor an exhibition initially planned for the spring that was disrupted by COVID-19. “Robert Wallace wrote the accompanying words for the Life essay,” she adds. “He tried to point out how statistics can be misleading, to give a more complex rendering of the circumstance of crime in the United States in the 1950s.”

Indeed, amid protests over the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Tony McDade and others—and a national reckoning with police brutality and institutional racism—the work of mid-century photographer Gordon Parks, who died in 2006, feels pressing, with a newly released monograph that depicts racial injustice with urgent, aesthetic power. A self-taught artist and humanitarian, Parks captures subjects that are often dismissed and marginalized, in their nuanced, full-throated humanity. For “The Atmosphere of Crime,” he used color film and natural light, though other stories for Life were usually shot in black and white; at the time of this series, he’d already worked for a decade as the magazine’s first African American staff photographer. Though only twelve of the 300 photos Parks made for the assignment were featured in the original issue, the essay illustrates for American readers how entwined race, poverty, policing and incarceration were at that time—and remain to this day.

In February, MoMA acquired the set of modern color prints of the plates Meister selected and sequenced for the book from the Gordon Parks Foundation. The museum planned to display a sample of these images, alongside works from other artists, in a dedicated fourth-floor gallery as part of the next phase of the reinstallation of their permanent collection. “The dividing lines between photojournalist and artist at that time in the history of photography were considered clear and absolute,” explains Meister. “But an important aspect of Parks’s legacy is that he ignored those boundaries, and that’s what makes the work equally at home on the walls of a museum as the pages of a magazine.”

In fact, the series inspired the museum to look more closely at the history of how crime has been documented by American photographers, placing Parks’s work on a trajectory so that viewers could appreciate his radical departure. “I can only hope that having such a compelling historical marker, against which we can compare what is happening today, encourages the recognition that this is a very seated, long standing problem,” furthers Meister. Published this summer by Steidl and The Gordon Parks Foundation, in collaboration with MoMA, the volume, titled The Atmosphere of Crime, 1957 includes 47 never-before-released images from the photographer’s six-week journey on the streets of New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles and Chicago, where the magazine sent him to document urban crime.

“Parks manages to capture with his camera incredibly complex ideas about the state of policing and the backdrop of what leads to so-called ‘criminal behavior,’” says Meister. “Through a variety of technical and artistic choices, he destabilizes our sense of what a criminal looks like.” For example, by cropping and blurring his natural light pictures, Parks—part advocate, part documentarian—creates intense, intimate tableaux that preserve the anonymity of the accused yet sharply illuminate the faces of law enforcement. According to Meister, the photographer believed his impact would be greatest working for such a widely circulated magazine. “There were some who critiqued him for selling out to white editors and a white audience,” she describes. “But I think Parks felt that these were the very people that he wanted to be able to teach to see the world through his eyes.” This particular series, he well understood, straddled two, fraught worlds; the images had to resonate with a mainstream, and therefore largely white, readership, yet also endure as exquisitely composed artworks that would continue to command viewers to look more closely at the realities of our society, well into the present.

in your life?

in your life?