“If we’re going to explore the power of the imagination, we couldn’t just take stuff off the shelf,” says architect Mónica Ponce de León, who along with Cynthia Davidson, nonprofit director of Anyone Corporation, are co-curators of the American Pavilion at this year’s 15th International Architecture Exhibition la Biennale di Venezia. “We believe commissioning speculative work was an important way to open up a conversation about how architects work and bring new ideas to the table.”

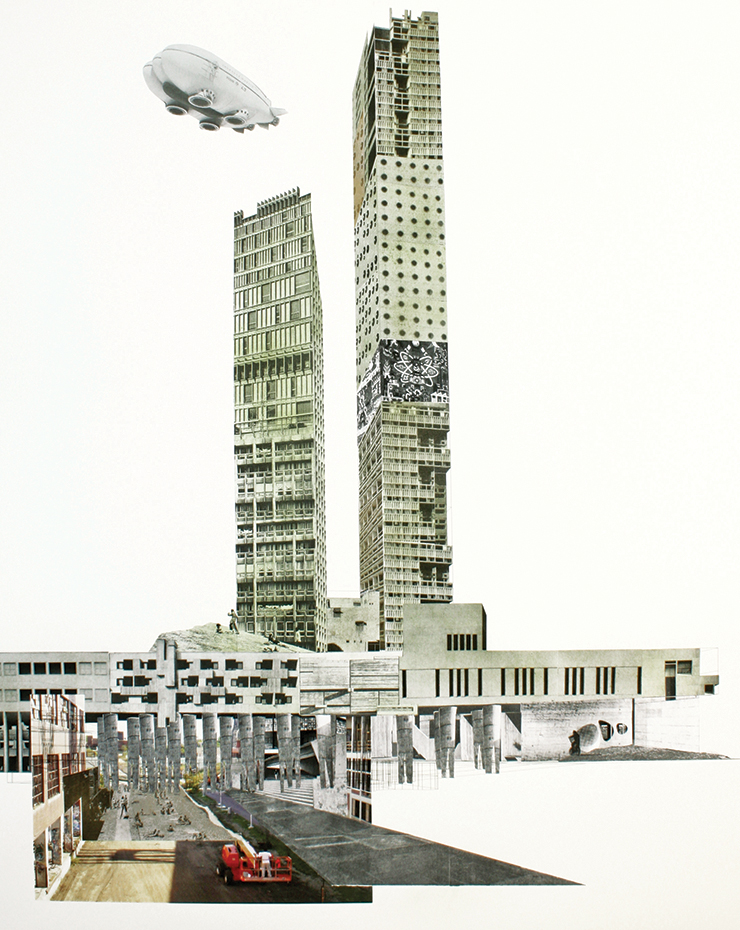

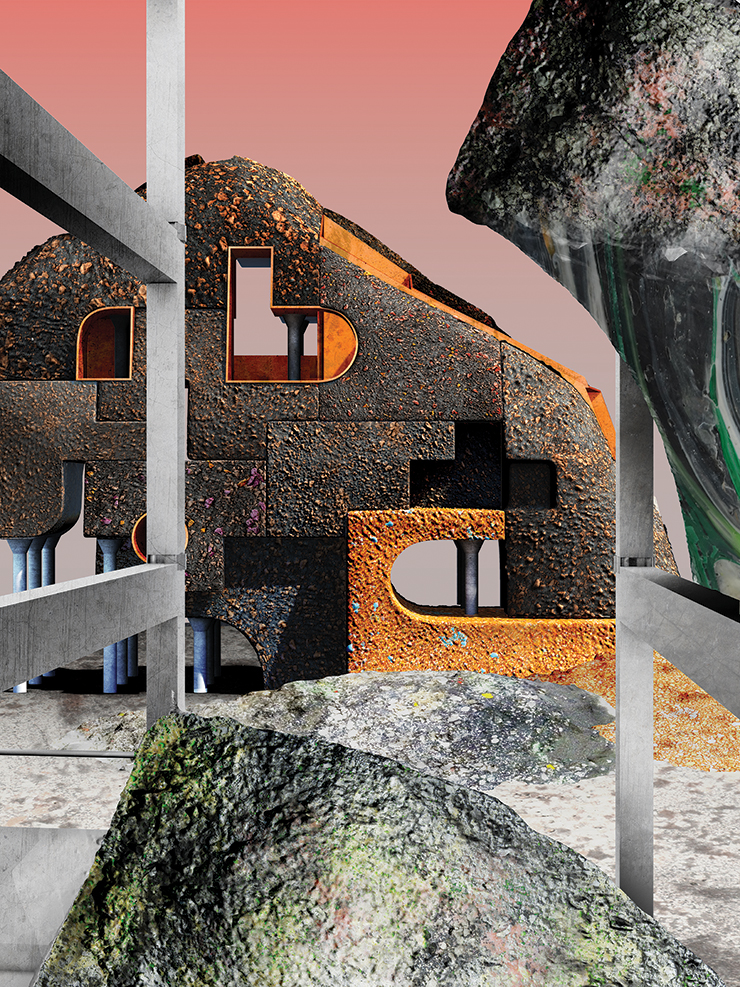

Unlike typical biennale exhibitions where existing structures have become the dominant attraction, this edition will showcase theoretical plans intended for sites selected by Detroit natives, while emphasizing abandoned areas in critical need of new life.

For the past year, the two curators have been immersed in the culture of the Motor City with “The Architectural Imagination,” their response to issues affecting post-industrial cities. Davidson is editor of Log, an architectural journal she launched in 2003, while Ponce de León—recently appointed dean at Princeton University’s School of Architecture—is principal architect at MPdL Studio. The two met while surveying Common Ground, the 2012 edition of the Venice Biennale curated by British architect David Chipperfield. “We think similarly about the capacity of architecture to catalyze cities,” says Davidson about their shared mission to redefine Detroit as an urban center while showcasing what architecture might accomplish in the age of the “freelance economy.”

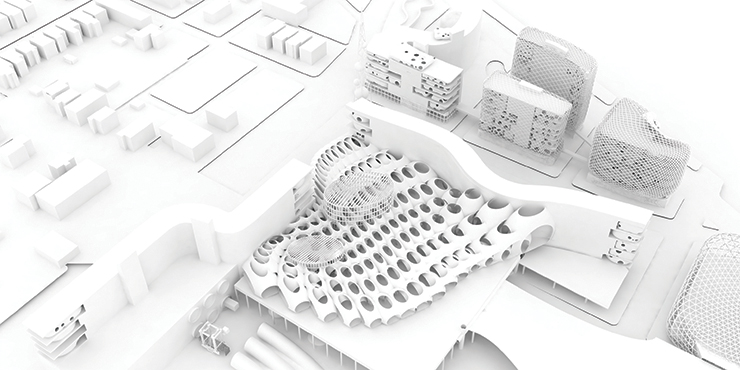

A Detroit advisory board helped develop criteria and oversee the selection of the four urban sites: a U.S. post office, the former Packard Automotive Plant, and the neighborhoods of Dequindre Cut/Eastern Market and Mexicantown. These locales will be the focus for the 12 architectural teams that represent a diverse cross-section of U.S. architectural practice while highlighting new modes of cultural production. “These places typify problems in Detroit and are very much representative of global issues,” insists Ponce de León. “We highlighted sites that could become models for other cities,” she adds, emphasizing the issues the architects will engage with—from housing, education and landscape to employment and health.

The 12 teams include A(n) Office, Detroit; BairBalliet, Columbus, Ohio; Greg Lynn FORM, Los Angeles; Mack Scogin Merrill Elam Architects, Atlanta; Marshall Brown Projects, Chicago; MOS Architects, New York; Pita & Bloom, Los Angeles; Present Future, Houston; Preston Scott Cohen, Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts; SAA/Stan Allen Architect, New York; T+E+A+M, Ann Arbor, Michigan; and Zago Architecture, Los Angeles.

Zago architects proposed a resettlement project at Dequindre Cut for Syrian refugees, including offices, classrooms, a clinic and food hall, while Marshall Brown Projects imagined a learning academy for pre-K through college inspired by an existing charter school that encompasses recreation, culture, health care and housing situated at the same site. According to Brown, his scheme is inspired by architect John Portman’s Renaissance Center downtown.

“This project returns architectural models, drawings, collages and videos to the American pavilion. The walls will be filled with original work made especially for Detroit and ‘The Architectural Imagination,’” says Davidson about the 1930s venue, built in a neoclassical style and managed by the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice. Log will function as a bookazine featuring essays on the 12 projects, while “My Detroit,” a postcard project of 20 images shot by 18 individuals will be printed and distributed during the Biennale. Davidson reviewed the 463 entries with photographer and sociologist Camilo José Vergara, who has relentlessly documented Detroit since 1985. The photos separately capture a distinct personal view and also present a rare portrait of Detroit.

“I have a very unique perspective on Detroit,” says Ponce de León, while discussing her tenure as dean at the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Michigan, which organized the show. “I’m sure you’ve heard the term ‘ruin porn,’” she says, commenting on images of derelict buildings and neighborhoods that have dominated the media and portray a negative stereotype of the city. “What has been left out is the reality of community in Detroit and individuals doing really powerful and interesting work.”

After the Biennale, the show will come full circle, traveling to Detroit in 2017 where it will be installed at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD). The exhibition proposals are programmed for mixed-use and focus on initiatives that the curators hope will send a more positive image of Detroit and beyond.

in your life?

in your life?