Running the length of Darja Bajagić’s middle finger is a tattoo in Cyrillic lettering that reads Xenia, the Russian saint to whom parents pray when their children go missing. “I learned of Xenia about two years ago and her story really resonated with me,” said the 27-year-old artist from her studio in Long Island City, Queens. It was a time when Bajagić was feeling overwhelmed by the grisly stories that provide the source imagery for her work—real-life sex crimes, violent porn, pedophilia—and she took comfort in learning about Xenia, who dedicated her life to protecting children and the homeless.

On Bajagić’s floor that day she had laid out several photos of women for a new series she was working on. She recounted the backstory of each: one murdered and one missing girl, two grieving parents, a busty porn star wearing an undersized Snoopy T-shirt, and a provocatively posed child swimsuit model. At the bottom of the painting she had printed in blue block letters: “God Bless Innocence.”

It’s a phrase borrowed from Bajagić’s new collaborator, convicted murderer Joseph Druce. She discovered Druce’s prison drawings while shopping on her favorite “murderabilia” website, Serial Killers Ink, and learned that he had quite a backstory of his own. After being chronically abused as a boy by various family members, he went on to kill a man who had made a pass at him. While serving a life sentence for that crime, he killed another man—a priest accused of molesting more than 130 boys—in his prison cell.

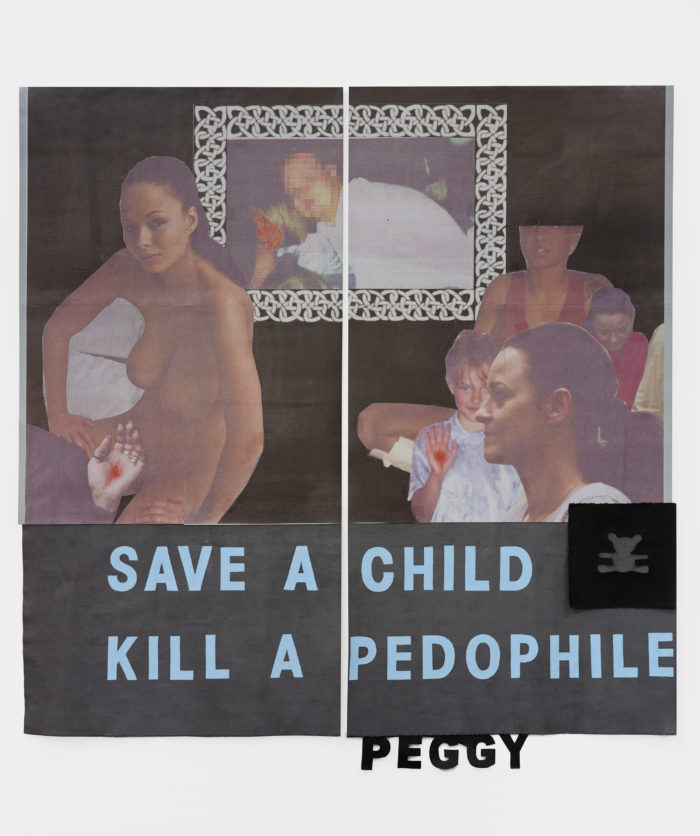

Bajagić wrote Druce a letter and proposed incorporating his drawings of pedophiles, which he pairs with slogans like “Save A Child, Kill A Pedophile,” into her paintings. “I like stories that have two sides,” she says. “What Druce is doing could be seen as bad or good, depending on your perspective. He's a ‘bad’ person—he is a murderer—but he found a way to make it good, to justify it.”

Her other subjects also tend to have a twist in their stories: a missing girl identified by her Playboy bunny tattoo, a decapitation victim whose headless body was dissected a second time by commenters viewing the photos on a gore website, a teen raped and fed to alligators—the latter of which is the subject of Bajagić’s new site-specific installation opening at Zurich’s LUMA Foundation in May.

“Darja is asking, where does the violence really occur?” says Vanessa Carlos, co-founder of Bajagić’s gallery, Carlos/Ishikawa. “The violence occurs when someone murdered the girl, then it occurs when people absorb the images on the internet. Does it occur again when Darja shows the work? She may be implicating herself or implicating us, but I don’t think she’s just propagating something. If her work is about images and consuming images, then it’s effective to show those images.”

But her work’s moral elasticity has gotten Bajagić into trouble in the past. Just before completing her MFA at Yale in 2014, she received a notice that she wouldn’t be graduating. Her work apparently hadn’t convinced the entire faculty, some of whom felt it hadn’t shown enough development.

Robert Storr, then the school’s dean, encouraged her to seek psychotherapy. Rochelle Feinstein, the head of the painting department, suggested she take a class on feminism. “I think they wanted me to take some kind of moral stake in the work that I wasn’t willing to take,” Bajagić says. “That’s not what my work is about. I want the viewer to come up with their own conclusions.” In the end she worked double-time her last semester and narrowly graduated.

Although her salacious imagery may have surprised some professors—Bajagić had applied with a body of monochromatic paintings, after all—violence has preoccupied her since adolescence, when a close friend was murdered. After that, Bajagić, who was born in Montenegro and raised between Egypt and Chicago, says her “very Eastern European” mother put her on lockdown. They spent nights watching Nancy Grace’s true-crime show and Bajagić started spending more time online, “reading on forums about weird things and looking at porn,” she says. “I'd go into chat rooms and pretend to be people I wasn’t. It was around then that I really started reading all of these different stories.”

She began making zines from the online narratives she discovered, and later pasted pictures of women atop Minimalist, monochromatic paintings in a way that resembled computer windows. “I think of it as a mirror onto the world,” she says of her work. “I'm putting back together things I find that almost want to be together in the world but aren’t.”

Hers is a world of little mercy—for either its subjects or its viewers. Like Thomas Hirschhorn’s corpse-strewn installations or the wasted women in Lars von Trier’s films, the punishing imagery may leave the observer feeling herself a victim of a cruel artist. But even if there’s little evidence here of Xenia’s compassion, one may take some comfort knowing that the saint’s good name is nevertheless guiding Bajagić’s hand.