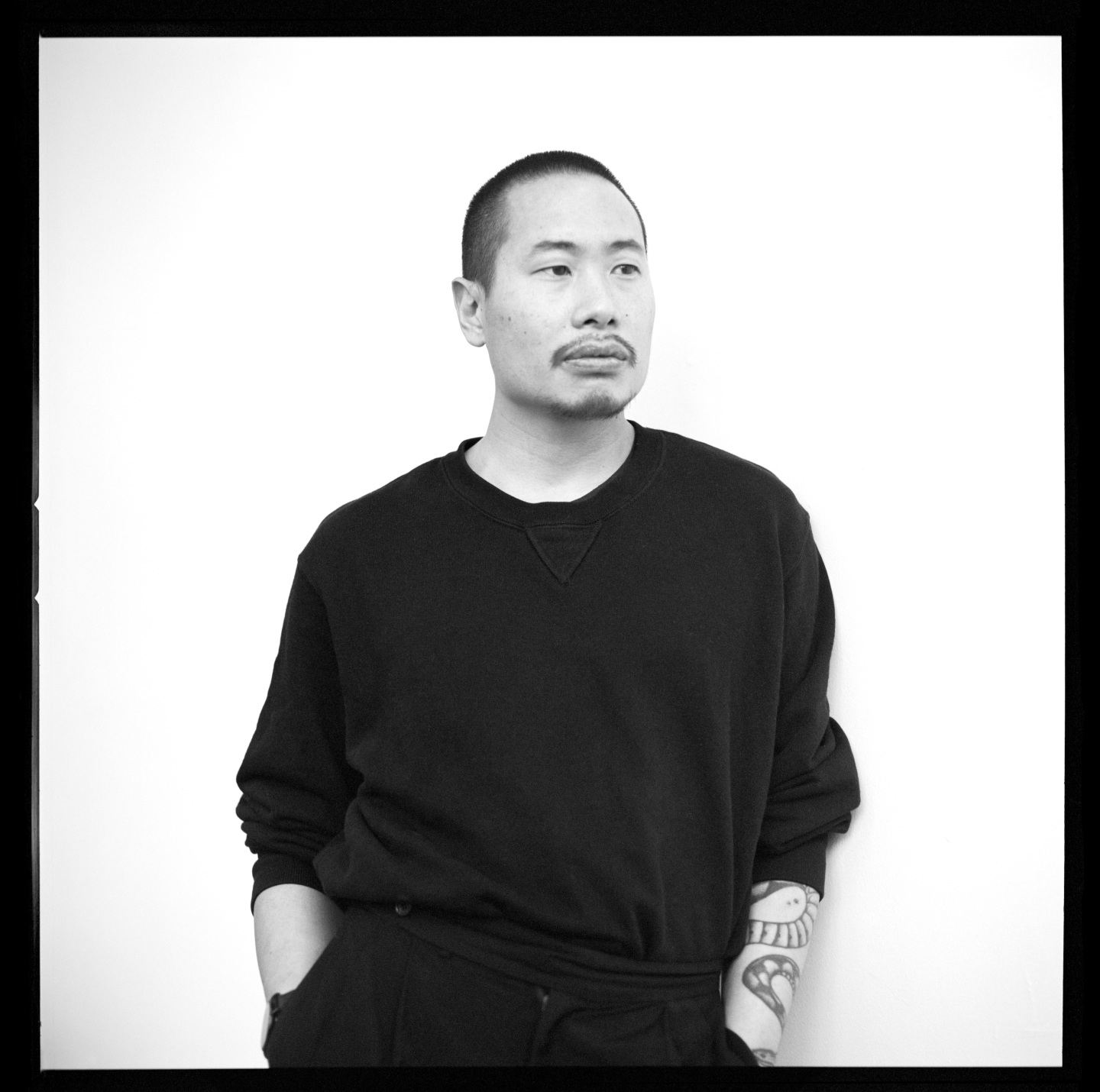

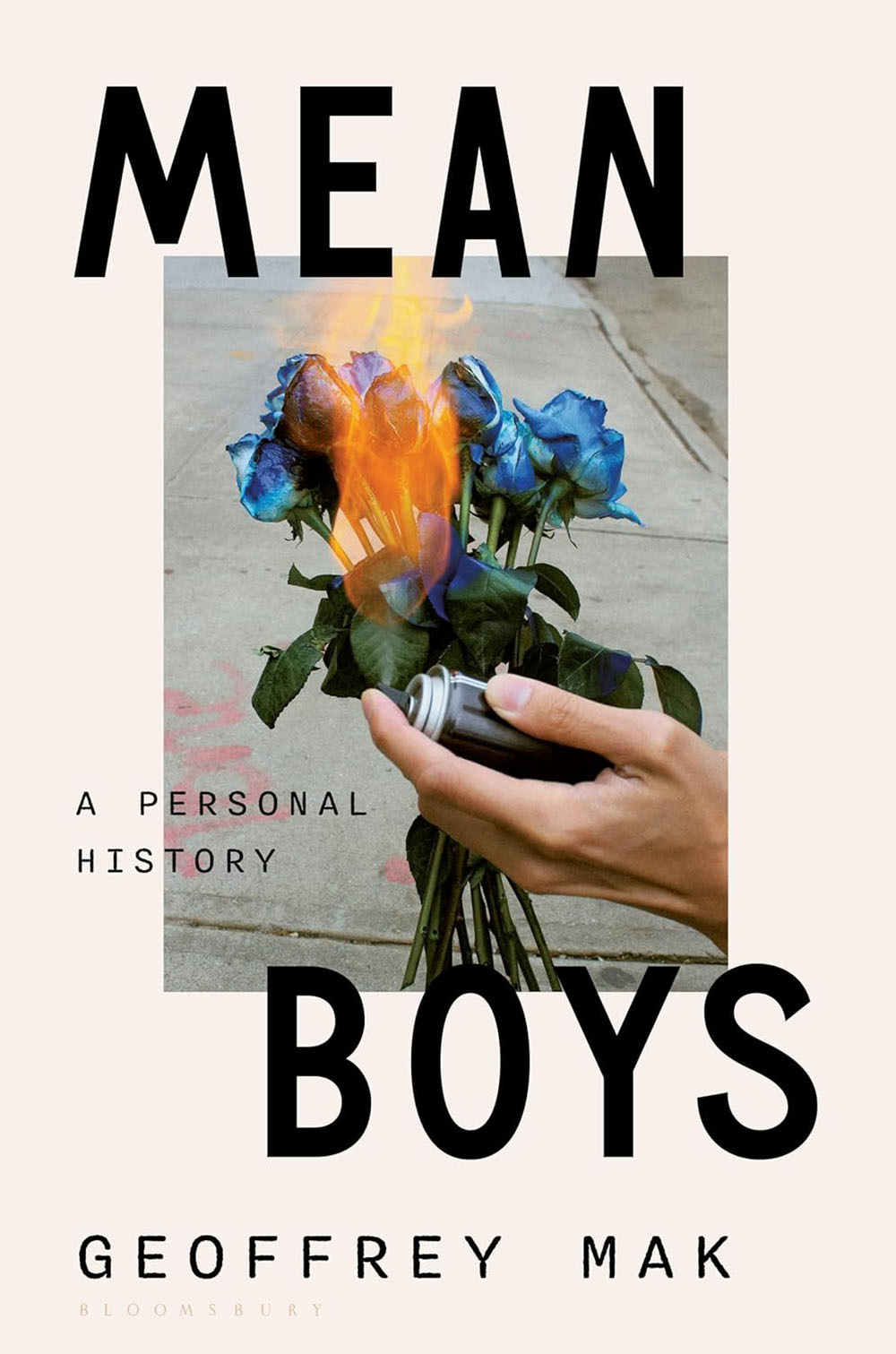

In Mean Boys, Geoffrey Mak’s debut book, everyone is mean. Parents, club kids, art-world intellectuals, childhood friends, AA sponsors. Everyone, perhaps surprisingly, also gets their moment of redemption: Homophobic parents reckon with the pain they’ve caused, welcoming their prodigal son home. Bitchy gays reveal deeper layers of kindness and authenticity. Even Mak himself, after experiencing a moment of utter spiritual crisis during a downward spiral at Berghain, manages to claw his way out.

Unlike the clarity of redemption offered by contemporary American evangelicalism—“washed clean by the blood of the lamb, pure and spotless”—the narrative Mak spins is more insoluble. After spending days pacing his mother’s garden in the middle of the pandemic lockdown and coming up empty-handed, he learns to sit with the mystery. He doesn’t become a better person, but he comes to understand himself a bit better. To mark the book’s release, I spoke with the writer about his evolving relationship to faith and the importance of empathizing with ideological enemies.

Liara Roux: I was raised in a homophobic Evangelical family and have a hard time walking into a church. Your passage on job as a masochist was revelatory to me. Describe your relationship to Christianity.

Geoffrey Mak: I am drawn to mysticism and the apophatic strain of Christianity. I took the evangelical notion of a “personal relationship with God” to an almost comic extreme. The transgressive, queer theologian Marcella Althaus-Reid writes [in Indecent Theology], “Our praxis should be one which prioritized beggars as theological partners for the ongoing orthopraxis of our church.” She comes from decades of Latin American liberation theology, which is oriented toward justice for the marginalized. Even Jesus was a transient.

My friend Linn Tonstad wrote a major book that uses the topology of lesbian clitoral sex as a way of understanding the abundant joy of the Holy Trinity. There’s exciting stuff out there, though it’s almost impossible to discover it outside of divinity schools like Yale or Harvard. If this whole writing thing doesn’t pan out, I might go to divinity school. I’ll never step into a church, though. Still can’t do it. What’s your relationship to Christianity today?

Roux: I love the idea of a queer hippie Jesus. The only churches I can bear are historical cathedral; I appreciate the architecture, but they feel demonic.

Mak: The Vatican will always feel kind of evil to me.

Roux: In the book, you engage with ostensibly evil “edgelord” alt-right texts in a very humanizing way without validating the more toxic elements they espouse. How do you strike this balance between empathy and being overly credulous?

Mak: Empathy is a dicey practice. Like the French aphorism “to understand all is to forgive all,” it is assumed that its natural outcome is forgiveness. Forgiveness is difficult—one must maintain love and judgment without one diminishing the other, holding two opposing ideas at once. I wrote about empathizing with Elliot Rodger [who killed six people in Isla Vista, California, in 2014], though I never felt credulous about his ideas. The judgment was always firm. In fact, his evil was so unambiguous that it was too easy to hate him. Instead of being in denial of the things I had in common with him, I had to empathize so that I could abandon them for good. And I have.

Roux: Whenever a text angers me, I try to sit with it. Often it’s provoking a reflection that’s very productive.

Mak: This Jungian notion of symmetrical twinning appears often in the Bible. “Forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors.” Or, “Why do you look at the speck of sawdust in your brother’s eye and pay no attention to the plank in your own eye?” Or simply, “Love your neighbor as yourself.” I think that to love someone who is the epitome of revulsion or abjection is to love yourself in a profoundly expansive way.

Roux: In the book, you describe a schizophrenic episode in Berlin, and the social fallout you experienced after. Did you feel “canceled”? What responses from community members were most helpful for you? What still stings?

Mak: A lot of people stopped fucking with me. I was a drug addict, and I have a lot of understanding for people who needed to cut me out of their lives, but I still felt abandoned. People felt okay abandoning me because they blamed me for my problems—a convenient narrative. Nobody bothered to visit me in the loony bin, except my friend Amanda [DeMarco], who I dedicated the book to. I’m more angry at the people who tried to help and abandoned me halfway than the people who didn’t help at all.

Roux: How did you feel about the rumors that Berghain was closing? Do you feel like Berghain is over?

Mak: I was relieved when I heard the (fake) news. Partly it’s because I live in New York now, and I don’t want other people having fun without me. When I was there last summer, it seemed to be in transition. When I was leaving the club for the airport at 6 in the morning, I told myself that I needed to move on; this chapter in my life had closed. I swore that I wouldn’t go back again unless a friend was DJing and invited me or something. But let’s be real, I’ll probably be back this summer. Help!

Roux: Which writers are you the most inspired by these days?

Mak: I’ll always have my trifecta of old white women: Alice Munro, Marilynne Robinson, and Joan Didion. Hilton Als showed me my voice. James Baldwin gave me my conviction. Grand Tour by Elisa Gonzalez and Dereliction by Gabrielle Octavia Rucker are two of the best poetry collections I have ever read. I am always thinking about them. What about you?

Roux: A friend gave me the complete fear of Kathy Acker recently, and it’s as amazing as everyone says it is. It's similar to this Hillary Clinton erotic fan-fiction I've been working on. Which essay in Mean Boys was the most fun to write?

Mak: I think “In Arcadia Ego.” I wrote most of that in one sitting—never really revised it—because it was supposed to be a Facebook post. Never in my most delusional fantasies did I think my Facebook post would one day end up in a book.

Roux: What's it like to be part of a literary power couple? You and Drew Zeiba are too cute!

Mak: I let myself be that dumb bitch who looks at pictures of my boyfriend on Instagram throughout the day to feel giddy. There’s one of him wearing a robin’s-egg blue Margiela vest that I picked out for him when we were vacationing in Berlin. He has a soft look, weary and inquisitive. You know him—he’s not a particularly soft person. After his grandmother died, he referred to his own grief as “corny.”

He sneers more than he smiles, but when he smiles, he has this look of complete trust and gratitude that turns me to jelly. He challenges me intellectually. We read Homer together, and we get into heated arguments about the definitions of words. He surprises me with gifts, books by writers I’ve never heard of, and revolutionized my approach to writing. He has taught me things. I feel like Beyoncé right before she released Lemonade.